How to Make $1 Billion in Labor Savings Real & Recurring

New York City municipal employees provide services New Yorkers rely on; their dedication during the pandemic is a testament to their work ethic and commitment to our city. Yet, as the City faces the worst fiscal crisis in generations, municipal workers are also facing the dire prospect of layoffs.

The City’s municipal labor unions have been integral to the management of prior fiscal crises; union leaders have made concessions or signed agreements generating savings in every recession or crisis since the 1970s. The Adopted Budget for Fiscal Year 2021 calls for $1 billion in recurring savings from negotiations with labor unions, yet no savings have been publicly identified or agreed upon to date. Instead, the Mayor is planning to initiate a layoff action.

To navigate this crisis and emerge on a firmer fiscal footing, City leaders should make hard choices and ask all stakeholders—including public labor unions—to share in the sacrifice. Widespread layoffs are undesirable, and should be a near-to-last resort. (It is worth noting that over 20,000 employees leave City service each year; hiring to fill half of the vacancies would reduce headcount by more than 10,000 annually.) This report outlines ways the City and labor unions can meet the target, including reforming health insurance benefits and improving productivity through changes to work rules codified in labor contracts, and avoid layoffs. The savings from fully implementing these options is far greater than $1 billion.

To the extent City and union leaders agree to recurring savings greater than $1 billion, savings can be used to provide wage increases in the next round of collective bargaining or to implement gain-sharing with employees.

Adopted Budget: Two-Year Wage Freeze and $1 Billion in Recurring Savings

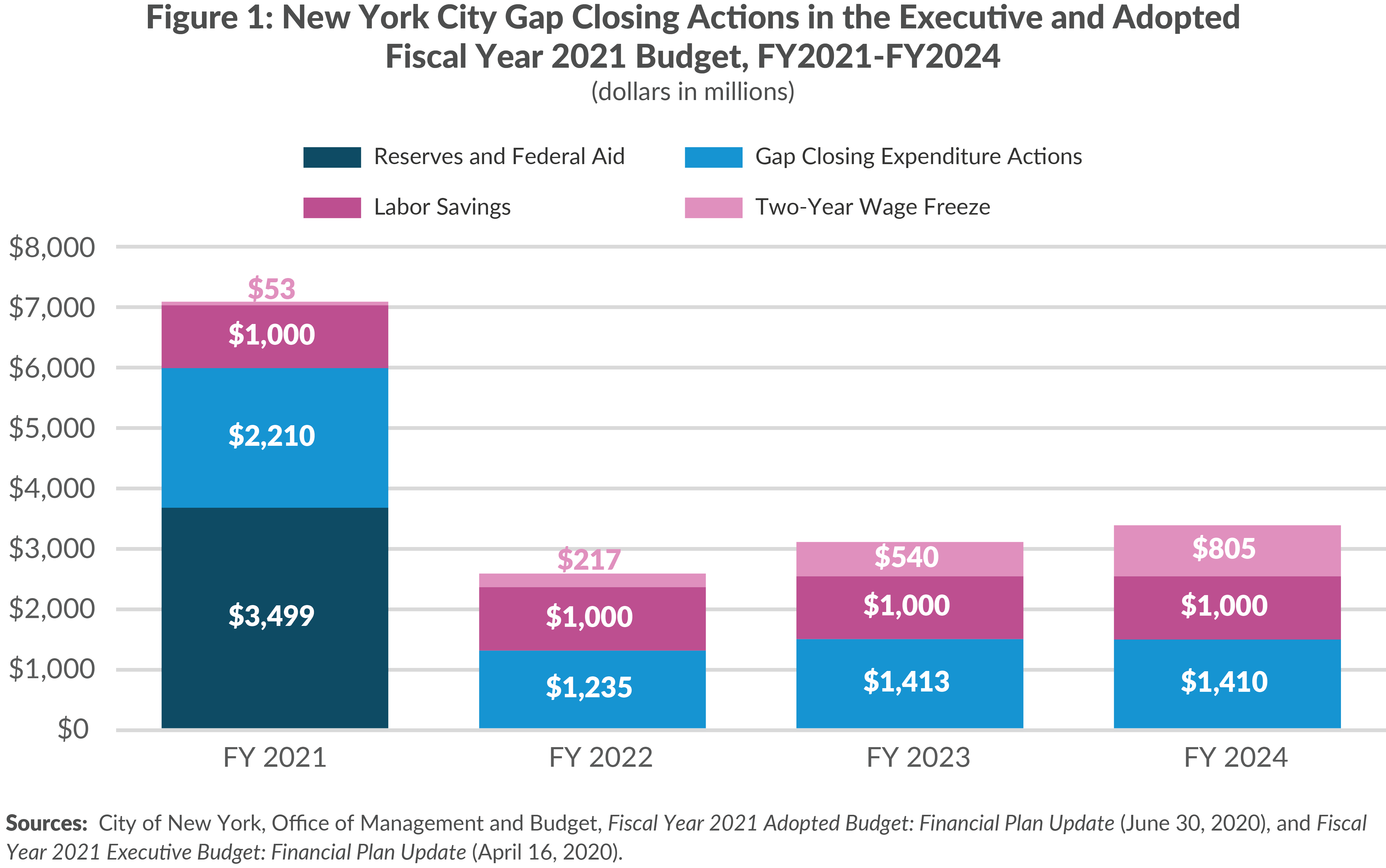

As part of its gap-closing plan, the Adopted Budget for Fiscal Year 2021 includes a placeholder for $1 billion in labor savings and eliminates funding that would have supported raises over two years. Savings total $1.1 billion in fiscal year 2021, increasing to $1.8 billion in fiscal year 2024. (See Figure 1.)

Together, these savings constitute approximately 2 percent of spending on personnel costs in fiscal year 2021. In fiscal year 2021 personnel costs are projected to be $50.2 billion of the $93.5 billion budget.1 Nearly $30 billion pays for salaries and wages and the remainder are for fringe benefits, notably pensions ($9.9 billion) and health insurance ($7.3 billion). (The $1 billion in labor savings is currently shown in the budget as a reduction in health insurance costs.) Salaries and wages are negotiated by each collective bargaining unit, while health insurance benefits are negotiated with the Municipal Labor Committee (MLC). Of compensation costs, health insurance premium costs have grown most rapidly; from fiscal year 2009 to fiscal year 2019 the premium grew by an annual average of 7.0 percent.2

Wage Freeze

Funding set aside in the City’s labor reserve for two future 1 percent raises, beginning for some unions as early as fiscal year 2021, was eliminated to save $53 million in fiscal year 2021, $217 million in fiscal year 2022, $540 million in fiscal year 2023, and $805 million in fiscal year 2024. Eliminating the funds essentially means the City’s starting position for negotiations will be a two-year wage freeze. Unions could still achieve wage increases during bargaining by funding them with other productivity and benefit changes.

The freeze does not affect raises to be paid out under collective bargaining agreements (CBAs) currently in effect, nor does it eliminate “step” or “lane” increases (based on years of service or education, respectively), or longevity payments (additional salary bumps for senior employees based on service length).3 Current CBAs for civilian employees provide for wage increases of 2.0 percent, 2.25 percent, and 3.0 percent, while the uniformed pattern is 2.25 percent, 2.5 percent, 3 percent.4

Given the depth of the City’s fiscal crisis, a wage freeze in the next round is appropriate. The municipal workforce has been spared much of the pain that private sector employees have experienced.5 New York City had 758,000 fewer private sector jobs in June 2020 than June 2019 (18.6 percent decline), virtually wiping out the gains of the recovery and sending the unemployment rate to a high of 20.4 percent.6 In contrast, the municipal workforce was essentially the same in April 2020 (325,614) as in April 2019 (326,061), decreasing by 447 positions or just 0.1 percent.

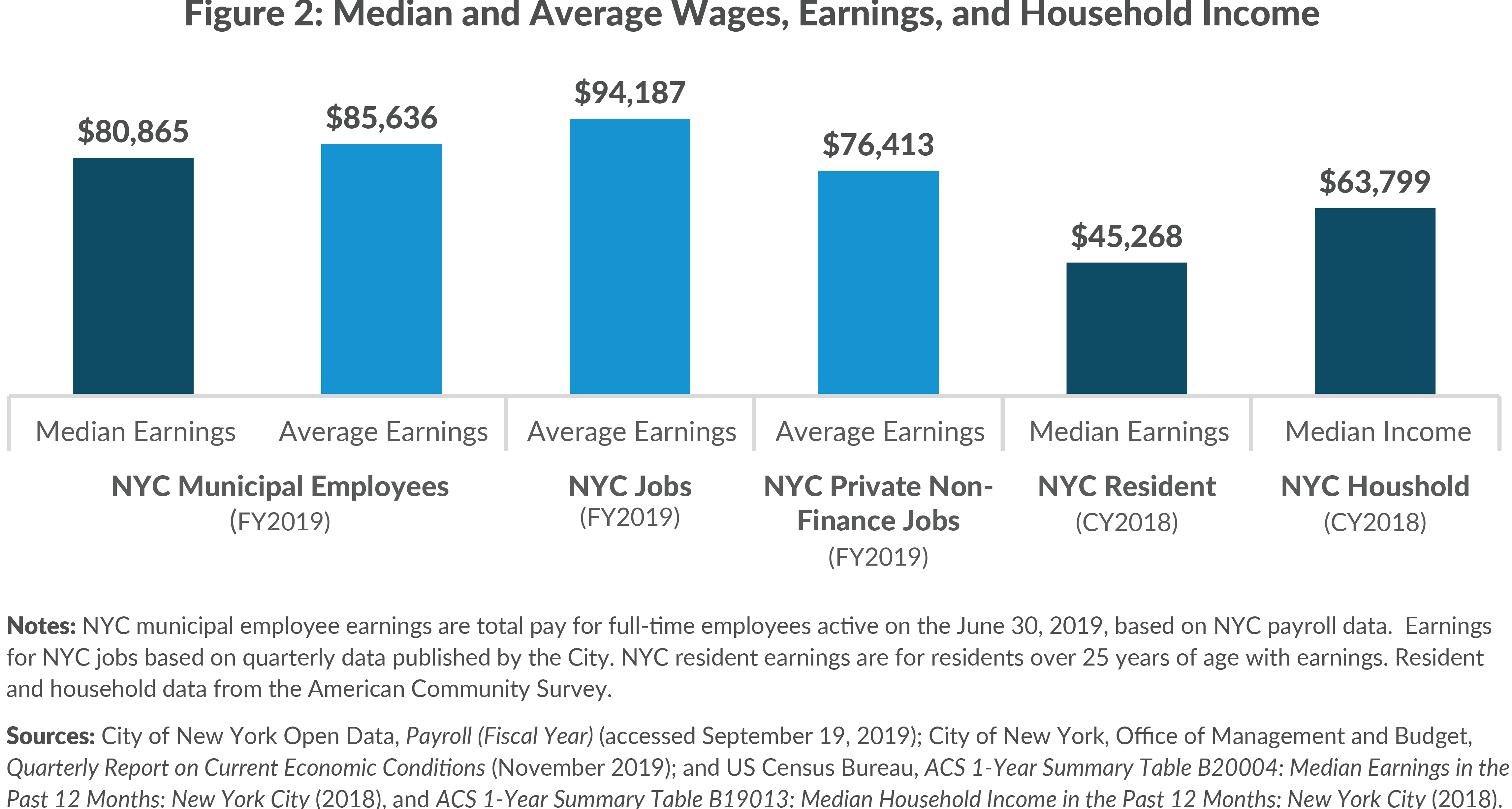

Compensation for municipal workers is also higher than for private employees (excluding the finance sector) and residents. (See Figure 2.) In fiscal year 2019 full-time City workers earned an average of $85,636, including overtime and other pay, while the average private sector non-finance employee earned $76,413.7 The median City worker earned $80,865, which is about 75 percent more than the median New York City resident, who had earnings of $45,268 in calendar year 2018. Municipal workers are the core of New York City’s middle class, and also enjoy compensation greater than most New York City’s residents.

Labor Savings

The Citizens Budget Commission (CBC) and other fiscal monitors have found the lack of specificity for how to achieve the $1 billion savings target highly concerning.8 Initially Mayor Bill de Blasio stated that failure to meet the target would result in 22,000 layoffs beginning in October 2020. In mid-August, the Mayor said he would move ahead with the layoffs absent federal aid or authority to borrow for operating expenses, and agencies were instructed to prepare savings plans and identify positions for layoffs.9

Layoffs negatively affect individuals and families who lose critical income and benefits. Furthermore, terminations are not based on merit, achievement, or ability; rather employees most recently hired are also generally the first to be laid off under provisions in CBAs and civil service law. As a result, more terminations are required to make the target because junior employees tend to have lower salaries.

Forgoing or limiting layoffs should be a shared goal of the Administration and labor leaders, and drive them to the bargaining table to identify ways to achieve the $1 billion savings target.

Approximately 23,000 employees leave the municipal workforce annually, an average separation rate of 7.1 percent per year.[10] The City could significantly reduce headcount and planned spending through attrition rather than layoffs, as it did following the Great Recession when the workforce shrank by more than 14,000 full-time and full-time equivalent positions over two years. In fiscal years 2010 and 2011 separation rates were 6.9 percent and 7.0 percent, while hiring rates were 4.2 percent and 4.9 percent, respectively.[11] This allowed City leaders to reduce the workforce with few layoffs. Applying these rates to today’s workforce would allow the City to fill almost two-thirds of vacancies and would reduce the workforce by approximately 23,000 within three years.

Attrition is preferable to layoffs because employees are mainly retiring or resigning for other employment, rather than losing their livelihoods. Furthermore, savings from attrition can be higher because retirees, a significant share of those who leave public service annually, are more highly compensated than recently hired employees facing layoffs. However, layoffs can be more targeted to specific titles or functions and can allow the City to rebalance the workforce through its hiring; in contrast, the City cannot control where reductions occur through attrition.

Another workforce reduction strategy is to provide an early retirement incentive (ERI) to encourage employees eligible or almost eligible to retire to do so. While often effective at increasing the number of retirements, savings from ERIs are lower than attrition or layoffs because of they are offset by the cost of the incentive, which can take the form of direct payments, pension credits (which increase long-run pension costs), or both. Furthermore, some benefits are provided to individuals who would have retired anyway; even the anticipation of a potential ERI delays the retirement of some employees who choose to wait for the benefit. CBC’s research on the New York State 2010 ERI program found that two-thirds of those participating were induced to retire, while one-third would have likely retired in the absence of the program.[12] Payroll savings were estimated at $1.4 billion, offset by $755 million in additional pension contributions, for a net benefit of $681 million. If half of the retirees were replaced, savings would have been just $272 million.

Labor Savings of $1 Billion Are Appropriate and Attainable

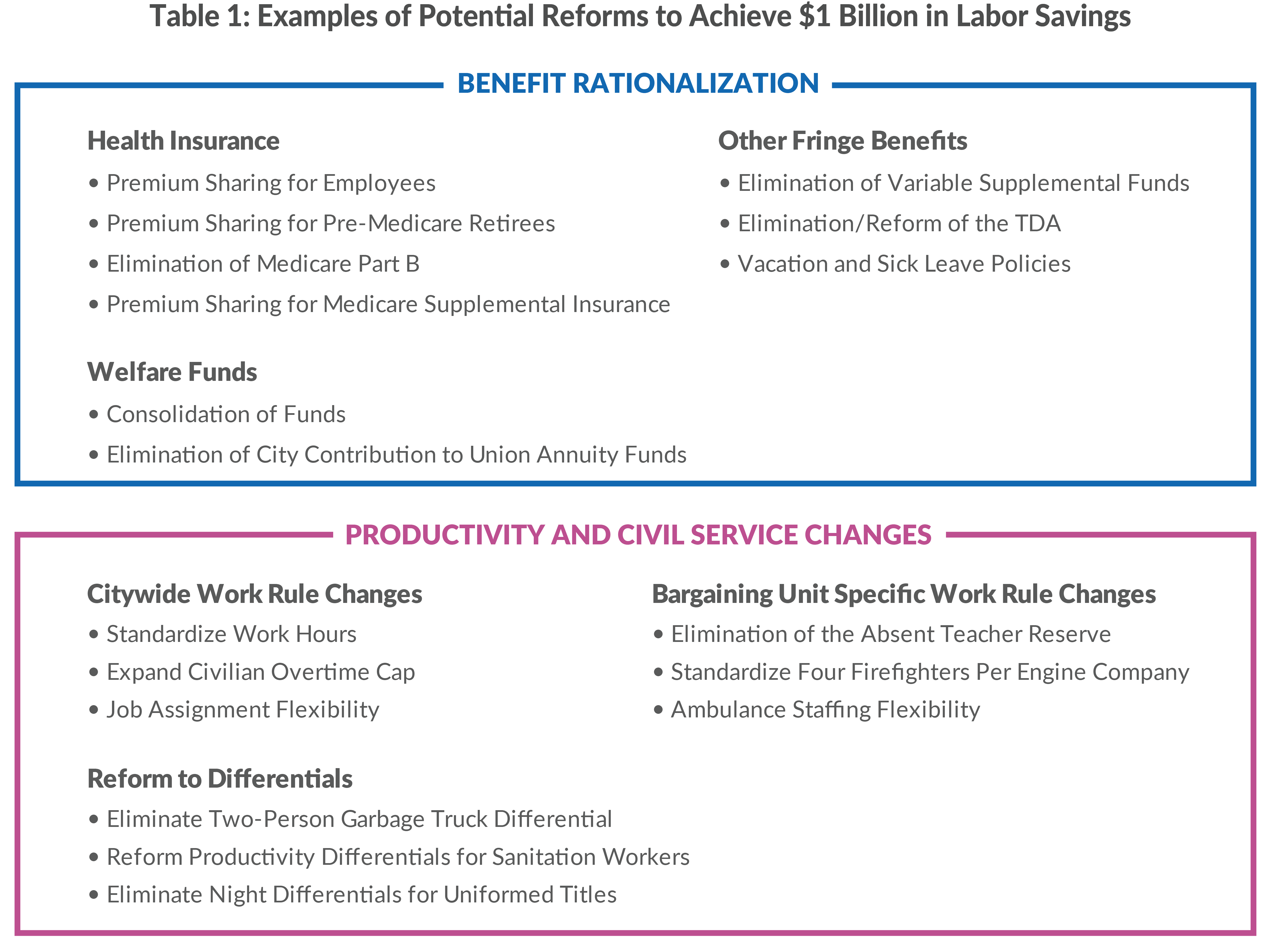

The best options to meet the savings target are those that achieve recurring savings by reducing the cost to provide services and by improving efficiency. Table 1 illustrates some options.13 Reforms to health insurance provide the best path to meet the target. Options to improve productivity yield relatively less in the short term, and often must be negotiated with individual collective bargaining units, but are critical to improving the capacity of city government to provide services effectively over time.

Benefit Rationalization

Part of why it costs New York City more to provide a service than other cities is the cost of employee compensation. This fiscal crisis presents an opportunity to rationalize benefits—maintaining attractive compensation packages while also bringing City benefits in line with other public employers. The modest cost would be shared across the City’s workforce of more than 325,000, rather than imposing severe consequences for a subset of employees facing layoffs.

Health Insurance for Active Employees

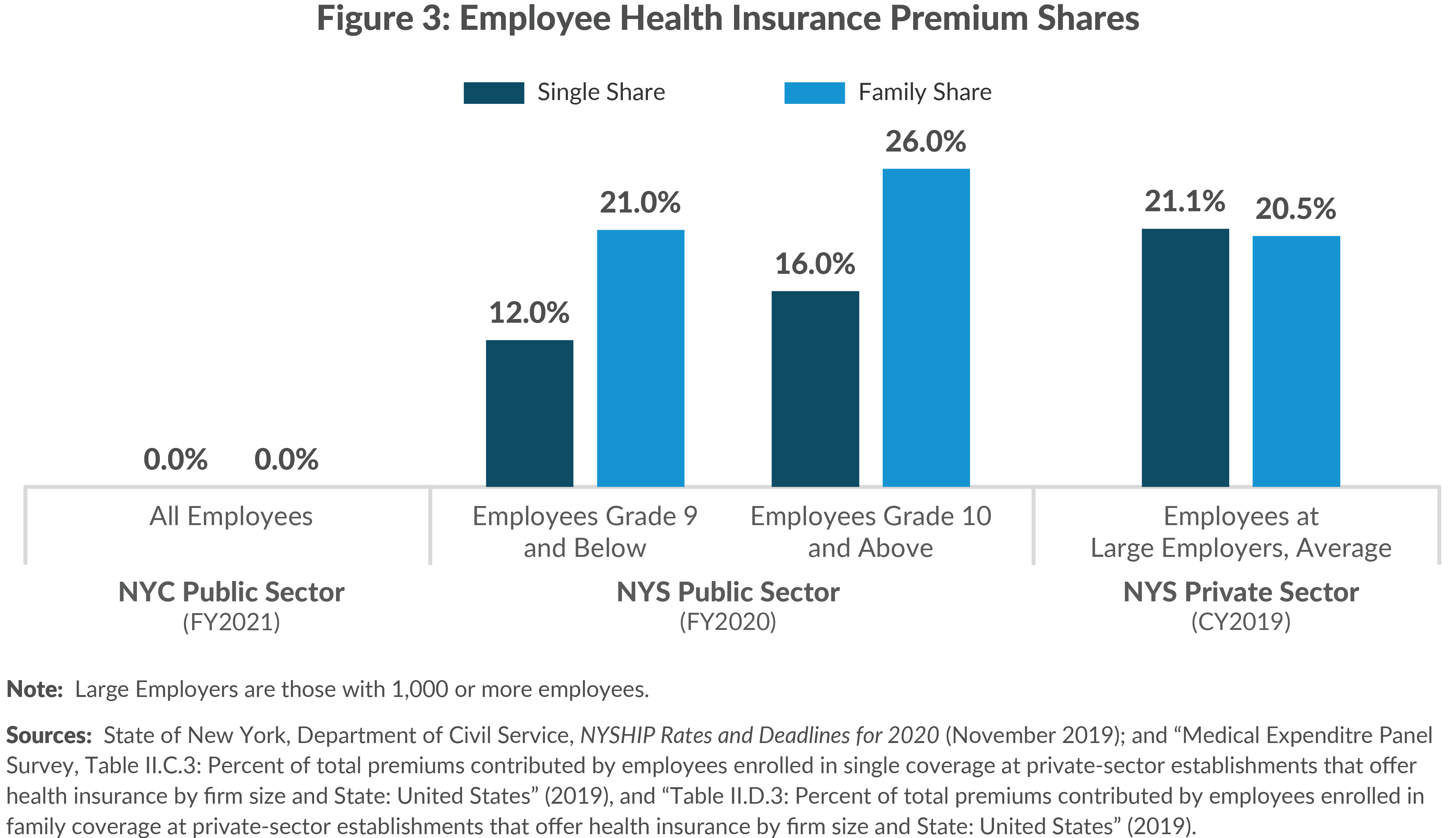

New York City is out of step with most public and private employers on health insurance premium-sharing.14 (See Figure 3.) For large firms in New York State, the premium contribution average 21.1 percent for single coverage and 20.5 percent for family coverage.15 In contrast, more than 95 percent of City municipal employees select health insurance plans that require no employee contribution toward the cost of the monthly premium, which in fiscal year 2021 costs the City more than $9,300 annually for an employee with no dependents and approximately $23,000 annually for an employee with dependents.16

The generosity of this benefit also exceeds that of other state and local governments. New York State requires graduated premium-sharing rates based on pay and coverage. For single coverage, employees earning up to around $43,000 (grade 9 or lower) contribute 12 percent of the premium, while those earning more contribute 16 percent.17 For family coverage, employees contribute the same share for the cost of a single premium and 26 percent or 31 percent, based on pay grade, for the additional cost of family coverage. Overall, the blended rate for family coverage is 21 percent for those in grade 9 or lower, and 26 percent for those in grade 10 or higher.

Health insurance should be a key focal point in negotiations between the Administration and the MLC. In 2014 the City and the MLC established a joint committee on health insurance with the goal of “bending the cost curve.” That partnership created both the rapport and process to identify several changes to care and cost structures successfully, but lost momentum in the second term of the Administration. (For CBC’s full review see The Health Care Savings Agreement: A Look Back and a Look Forward.) This partnership should be reinvigorated with the goal of implementing a new premium-sharing arrangement. Even modest employee contributions can generate significant savings without reducing the attractiveness of working for the City or creating excessive burdens for employees.

Premium sharing can be structured in many ways. Contributions can be consistent across employees, either as a share of the premium or a flat amount. Contributions also can be graduated, for example, based on the type of plan or employee salary. Other alternatives include higher contribution rates for managerial employees or newly hired employees.

CBC’s Hard Choices That Can Balance New York City’s Budget recommended premium contributions that are based on salary and type of premium. Fully implemented, employees with salaries below $65,000 would pay 6 percent of single coverage and 8 percent of family coverage (about $21 or $72, per pay period, respectively). Employees with salaries of $65,000 or more would pay 14 percent for single coverage and 16 percent for family coverage (about $48 or $144, per pay period, respectively.) Total savings to the City would be about $675 million.

CBC previously recommended employees contribute 10 percent for single coverage and 25 percent for family coverage based on private sector and State averages. Employees would contribute $34 per pay period for single coverage and $225 per pay period for family coverage, garnering City savings of $1.1 billion annually. Initially implementing rates at half that amount— 5 percent for single coverage and 12.5 percent for family coverage– would yield savings of $531 million.

Health Insurance for Retirees

After 10 years of full-time service, City employees are eligible for pre-Medicare retiree health insurance benefits with no responsibility for any of the premium cost, as well as Medicare Part B reimbursement and supplemental Medicare policies at no cost.18 The annual cost of these benefits was $2.2 billion in fiscal year 2020.19 Most private sector employers no longer offer any retiree health insurance, and state and local governments offering the benefit require significant premium-sharing or graduate the benefit based on length of service. That is, employees with 30 years of service are required to pay less of the premium than those with 10 years of service.

A contribution of 16 percent of the premium for pre-Medicare retirees in fiscal year 2021 would save about $224 million. CBC has previously recommended retirees contribute 50 percent of the premium for pre-Medicare health insurance, which would save $700 million. Contribution rates could also be scaled based on years of service; for example, retirees with 10 years of service could be asked to contribute 75 percent, while those with 20 years would contribute 50 percent and those with 30 years would contribute 25 percent.

Retirees age 65 and over are eligible for Medicare. Part A covers inpatient services and hospital care; it is provided by the federal government at no cost to individuals who have contributed payroll taxes for at least 10 years. Part B covers medically necessary and preventative services, including doctor visits, as well as other services not covered by Part A. Part B premiums are set by the federal government on a sliding scale based on income; annual retiree costs range from $1,735 to $5,899.20 The City provides a full reimbursement of all Part B costs, including to high-income retirees with more than $100,000 in income. City retirees can also enroll in supplemental Medicare policies offered by GHI or HIP with no employee premium share; in fiscal year 2021 these policies are estimated to cost the City approximately $2,370 per person.21

Elimination of Medicare Part B premium reimbursement and the income-related monthly adjustment amount (IRMAA) would save the City about $400 million a year. If 50 percent premium contribution was also required for Medicare Supplemental health plan policies, the City would save about $250 million. If Medicare Part B and IRMAA are eliminated and a 50 percent premium contribution is required, a single retiree enrolled in Medicare would be paying $2,885 year, while a retired couple would pay $5,770 per year. Contribution rates could also be scaled based on years of service.

Other changes to retiree health insurance also could be considered. For example, the City could require pre-Medicare retirees who are eligible for insurance through an employer (either their own or their spouses’) to enroll in that plan. The years of service required to be eligible for health insurance could be increased for current employees, as was negotiated with the United Federation of Teachers (UFT), which now requires 15 years of service.

Consolidation of Welfare Funds

The City makes per employee (and often per retiree) contributions to 73 distinct welfare funds administered by individual unions. 22 These funds most commonly provide prescription drug coverage and offer medical and dental plans, but also provide a variety of other benefits, such as scholarships, determined by each collective bargaining unit. Prior CBC work found many funds incur excessive administrative expenses, build unnecessary reserves, or suffer from mismanagement, including running deficits.23

The City should work with the MLC to consolidate welfare funds to leverage economies of scale for prescription drugs and other medical benefits. City payments to welfare funds are projected to exceed $1.3 billion in fiscal year 2020; CBC previously estimated consolidation could reduce costs by $164 million without a benefit cut. Members could opt for other nonmedical benefits under a cafeteria plan.24 As part of modernizing its health insurance arrangements, the City also could explore offering health insurance plans that include prescription drug coverage.

Elimination of City Contribution to Union Annuity Funds

Unions for uniformed employees, skilled trade workers, and some others manage annuity funds to which the City contributes per member annually. These contributions totaled $124 million in fiscal year 2020 in addition to the nearly $10 billion in pension contributions made to the City. The City offers its employees defined benefit pension plans that are relatively generous, even as compared to those provided to State workers. Pension benefits are constitutionally protected and can only be modified for future employees; however, City contributions to annuity funds are negotiated with each union, and should be reduced or eliminated.

Elimination of Variable Supplement Funds

Uniformed employees of the New York Police Department, the Fire Department, and the Department of Correction who retire for service are eligible to receive an annual statutorily defined Variable Supplement Fund (VSF) payment in addition to their pensions. In addition, members in Police and Fire department who remain on active duty after 20 years and ultimately retire for service may also be entitled to the VSF DROP (Deferred Retirement Option Plan), guaranteeing a lump sum payment. VSF payments are not constitutionally protected and can be modified or eliminated by the New York State Legislature.

VSFs are distinct from pension funds and have their own significant assets, estimated at $4.9 billion for the police, $842 million for fire, and $416 million for corrections. When these assets are insufficient to make payments to retirees, the VSFs are funded with a transfer from the pension funds, effectively reducing the investment return of the pension funds. The transfers totaled $1.5 billion in fiscal year 2018 and $500 million in fiscal year 2019, and $552 million in VSF payments were made to retirees in fiscal year 2019.

The City should seek State legislation to eliminate the VSFs and have the assets transferred to the main pension funds. In addition to short-term budget savings, the long-term benefit include an improvement of the funding ratio of the uniformed pension funds and preservation of core retirement benefits. Currently, the FIRE pension fund has the lowest funded ratio of 65.4 percent; the POLICE pension has a higher ratio of 82.2 percent as of fiscal year 2019.

Reform or Elimination of the TDA

Teachers and other pedagogical employees can deposit funds into a tax-deferred annuity (TDA) that offers a fixed return investment option, guaranteeing either a 7.0 percent or 8.25 percent return.25 The fund is similar to a money market account that allows participants to withdraw money freely, but the returns paid are immensely larger than would typically be paid for such an account in this persistently low interest rate environment. CBC estimates the value of this taxpayer-provided guarantee is approximately $1.2 billion annually.

The TDA is managed by the Teachers Retirement System (TRS), and the much smaller Board of Education Retirement System (BERS), which invests TDA funds along with its own assets, and uses its own assets to ensure returns are paid to TDA investors if investment returns are not met. This makes TRS highly leveraged, heightens the vulnerability to market losses, and, ultimately, threatens the ability to provide pension payments.

The guaranteed return on the fixed return fund should be sharply reduced through State legislation. The UFT and the City previously agreed to reduce the rate to 7 percent in 2009 in the course of collective bargaining, and the change was codified later that year (the rate remains 8.25 percent for non-UFT members in TRS and BERS). Alternatively, reforms could be implemented to reduce the risk (and cost) by converting the fixed return to a variable return or a similar plan offered to federal employees.26

Vacation and Sick Leave Policies

For most titles employees accrue annual leave at a rate of 15 work days per year in the first 4 years of service, 20 works days per year in the 5th through 7th years, 25 work days in the 8th through 14th years, and 27 days per year from 15th year of service on. Employees can accumulate and carry forward vacation time. City employees also accrue one sick day per month of work and may carry forward an unlimited number of days. Many private sector employers offer less generous vacation time benefits, including “use it or lose it” provisions. Savings could be achieved by reducing the annual leave accrual modestly; a one-day a year reduction for civilian employees would save about $28 million. Another approach is to implement caps on how much leave can be carried forward and in certain cases cashed out at separation.

Productivity and Civil Service Reform

Extend Overtime Cap to Skilled Trades and Uniformed Employees

The City has an “overtime cap” for civilian employees excluding skilled trades; those whose compensation reaches $87,860 instead receive compensatory time for overtime hours worked.27 In recent years overtime hours and pay among uniformed and skilled trades employees has increased substantially. Furthermore, including overtime earnings in pension calculations provides an incentive for senior, more highly paid employees to seek overtime work as they near retirement.

The Office of Management and Budget has worked with agencies to make operational changes to limit overtime. Absent greater changes to work rules or staffing models that drive some of need for overtime, the City could reduce overtime for skilled trades and uniformed employees through the implementation of overtime caps. Uniformed overtime was $1.1 billion in fiscal year 2019, while employees in skilled trades earned about $100 million in overtime. On average, uniform employees work 234 hours of overtime, earning nearly $16,000; for employees in the trades, overtime hours average 250 annually, with overtime earnings exceeding $19,000.28 In fiscal year 2019 uniformed and skilled trade employees earned about $360 million of overtime in excess of 15 percent of their salaries; reducing the overtime hours could generate substantial savings.

Job Assignment Flexibility

Many CBAs limit the assignments of an employee to a narrow set of duties and relies on seniority for assignments, such as overtime or desirable postings. This limits the ability of managers to deploy staff effectively. Greater flexibility to assign employees, and to ask employees to perform duties out of their job description for a temporary assignment in response to a specific need, would facilitate the most effective use of the City’s workforce.29 One way to accomplish this would be to redefine or create new titles that better reflect modern operations. For example, at the New York City Housing Authority, there are more than 4,300 caretakers and maintenance workers who are not permitted to complete basic preventative and maintenance work that must be done by the fewer than 2,000 skilled trades workers, who are more highly compensated. As a result, simple repairs require multiple skilled trades employees, which extends repair times and increases costs.

Standardize Work Hours

Full-time employee schedules require 35 hours, 37.5 hours, or 40 hours of work per week. CBC has previously called for a forty-hour work week for all employees; depending on how this is implemented it would facilitate some shrinking of the workforce and associated savings (or increase services).

Elimination of the Absent Teacher Reserve

The Absent Teacher Reserve (ATR) should be a temporary stop for teachers whose positions are eliminated due to budget cuts or enrollment declines, not a permanent, paid assignment.30 In fiscal year 2018 the City spent $136 million on the ATR; recent efforts have tried to generate annual savings of $80 million, which would bring the annual expenditure to about $56 million. The City should not continue to pay teachers full salary unless they are actively in the classroom providing instruction. Recent DOE initiatives to place ATR teachers have likely moved many qualified teachers into classrooms. If teachers are not qualified (reflected in poor assessments) or have disciplinary records that prevent them from being assigned to teaching positions, they should be offered alternate employment within the DOE (at the corresponding salary for that position), or given the opportunity to resign or retire.

Standardize Four Firefighters Per Engine Company

Most fire engine companies at the Fire Department (FDNY) operate with a crew of four firefighters and one officer; however, up to 20 engine companies can be staffed with five firefighters and one officer under an agreement negotiated between the de Blasio Administration and the Uniformed Firefighters Association. The City could make four firefighters the standard staffing for engine companies.

Ambulance Staffing Flexibility

The Regional Emergency Medical Service Council for New York City (NYC-REMSCO) requires New York City to staff an advanced life support (ALS) ambulance with two paramedics and a basic life support (BLS) ambulance with two emergency medical technicians (EMTs). All other jurisdictions in New York are permitted to staff ALS ambulances with one paramedic and one EMT. The City should be given the flexibility to shift at least half of the ALS ambulances to a one paramedic, one EMT staffing model. This could allow for an increase in the number of ALS ambulances, which are dispatched to life-threatening emergencies where response time is critical. If the number of ALS ambulances does not double, the change could also generate savings because paramedic staff could decrease by attrition, or paramedic overtime hours, which increased 50 percent from fiscal year 2014 to fiscal year 2019, could decrease.31

Reform to Differentials

Certain contracts provide differentials—additional pay for specific assignments—that increase earnings. Differentials are intended to compensate for less desirable assignments, such as overnight shifts; compensate for additional efforts, such as operating a more complicated vehicle or machine; or incentivize productivity. However, these differentials should be reassessed periodically and revised to reflect current working conditions. Below are a few examples of differentials that should be eliminated or reformulated.

- The United Sanitationmen’s Association (USA) contract for sanitation workers provides a range of differential payments, many of which incentivize what have become standard operating procedures or, in some cases, are paid even when productivity targets are not met. As these differentials provide substantial compensation to sanitation workers (other pay, excluding overtime, averaged $13,356 in fiscal year 2019), the pay scale for workers should be revised to establish new productivity targets and compensation structures that would improve collection operations while maintaining some of the workers’ currently enhanced earnings.

In 1980, when the City and USA agreed to reduce the number of workers on a garbage truck from three to two, and workers were given a differential to compensate for increased work and higher productivity. Forty years later, sanitation workers continue to receive this differential, even as two-person trucks are now standard operating procedure.32 IBO estimates the differential cost nearly $43 million in fiscal year 2018, with the average worker receiving more than $7,000 annually.

The CBA also provides sanitation workers with bonus payments for achieving productivity targets. DSNY has not met the refuse productivity target citywide since fiscal year 2005 and has never met the recycling target; yet the differentials still have been paid.33 The productivity program should be eliminated and differentials for productivity should only be given for measurable improvements in cost-effectiveness.

- Most of the uniformed worker contracts include night shift differentials, many instituted in the early 1970s, to increase pay for work between the hours of 4 p.m. and 8 a.m. Some of these payments have already been scaled back for newly hired employees, especially in their early years of service. The CBA for firefighters, where many firefighters swap shifts to have two back-to-back shifts covering 24 hours, converted the differential to a lump sum payment equal to 5.7 percent of base salary, recognizing that overnight work is standard for this title. These differentials should be eliminated where facilities and services are provided around the clock; the higher salaries and benefits afforded to most uniformed workers already reflect the expectation for working on nights, weekends, and holidays.

Conclusion

The City is in the midst of an historic fiscal crisis—the speed and trajectory of the recovery is uncertain and substantial downside risk remains. It is imperative for labor unions to negotiate savings with the City. There are numerous avenues that could be explored to secure the $1 billion in labor savings and avert layoffs, including premium-sharing for employee and retiree health insurance, changes to welfare fund benefits, modifications to work rules, such as ambulance and fire engine staffing, and modernizing productivity differentials for sanitation workers.

Download Report

How to Make $1 Billion in Labor Savings Real & RecurringFootnotes

- Adjusted for prepayments, reserves, and withdrawals from the Retiree Health Benefit Trust. Also includes interfund agreements. See: City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Adopted Fiscal Year 2021 Budget: Financial Plan (June 30, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/fp6-20.pdf.

- For private sector employees in New York, premiums for single coverage grew 4.4 percent annually and premiums for family plans grew 5.2 percent annually from calendar year 2009 to 2019. Sources: City of New York, Office of Labor Relations, email to Citizens Budget Commission staff (August 28, 2020); and Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, Table X.C (2019), Table X.D (2019), and 2009 editions, https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/quick_tables_search.jsp?component=2&subcomponent=2&year=-1&tableSeries=10&tableSubSeries=&searchText=&searchMethod=3.

- Maria Doulis, 7 Things New Yorkers Should Know About Municipal Labor Contracts in New York City, Citizens Budget Commission (May 19, 2013), https://cbcny.org/sites/default/files/REPORT_7ThingsUnions_05202013.pdf.

- In this round of bargaining, civilian contracts average 43 months and include two 0.25 percent increases in fund contributions, while the uniformed pattern is provides raises over 36 months. Employees in many unions have already received the last raise of the current contract period. Source: CBC staff review of collective bargaining agreements on City of New York, Office of Labor Relations, “Recent Agreements & Prevailing Rate Consent Determinations” (accessed August 2, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/site/olr/labor/labor-recent-agreements.page; and City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Executive Fiscal Year 2021 Budget: Message of the Mayor (April 16, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/mm4-20.pdf.

- Most of the job losses have been concentrated in lower-paying private sector industries such as accommodation, food service, and retail trade. Fewer higher paid private sector workers have been laid off to date.

- From April 2019 to April 2020 job losses in the private sector were even higher: 887,200 jobs (-21.8 percent). Source: City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, NYC Employment Data (NSA)-June 2020 (July 17, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/csv/nycemploy-nsa06-20.csv.

- Compensation in the finance sector is high and skews the overall citywide average. For fiscal year 2019 the average wage rate for all private employees was $94,187; finance sector employees averaged $303,111 while non-finance private sector employees averaged $76,413. Private sector fiscal year average is the average of quarterly data. Source: CBC analysis of City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Quarterly Report of Economic Conditions (November 2019), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/ec11-19.pdf.

- Office of the New York State Comptroller, Review of the Financial Plan of the City of New York: Report 2-2021 (August 2020), https://www.osc.state.ny.us/sites/default/files/reports/documents/pdf/2020-08/rpt-2-2021.pdf; New York State Financial Control Board, Long-Term Budgetary Risks from COVID-19 (July 29, 2020), http://www.fcb.state.ny.us/pdf/FCBNY20200729_StaffReport.pdf; and Office of the New York City Comptroller, Comments on New York City’s Fiscal Year 2021 Adopted Budget (August 3, 2020), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/Comments-on-New-York-Citys-2021-AdoptedBudget.pdf.

- City of New York, Office of the Mayor, Transcript: Mayor Holds Media Availability (August 12, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/584-20/transcript-mayor-de-blasio-holds-media-availability.

- Citywide separation rate is from data including the New York City Housing Authority and New York City Public Housing Authority; that rate is applied to City headcount excluding those agencies. See: City of New York, Department of Citywide Administrative Services, NYC Government: Workforce Profile Report (Fiscal Year 2018), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/dcas/downloads/pdf/reports/workforce_profile_report_fy_2018.pdf.

- City of New York, Department of Citywide Administrative Services, NYC Government: Workforce Profile Report (Fiscal Year 2018), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/dcas/downloads/pdf/reports/workforce_profile_report_fy_2018.pdf.

- The 2010 ERI was available to NYS employees and local governments could opt in; members of the police and fire retirement fund were ineligible. NYC did not participate. A total of 14,371 employees participated. See: Tammy Gamerman, “How Much Did New York’s 2010 Early Retirement Incentive Save?” Citizens Budget Commission Blog (October 25, 2011), https://cbcny.org/research/how-much-did-new-yorks-2010-early-retirement-incentive-save.

- For more information on City health insurance and a comparison with the private sector, see: Maria Doulis, Everybody’s Doing It: Health Insurance Premium-Sharing by Employees and Retirees in the Public and Private Sectors, Citizens Budget Commission (January 27, 2013), https://cbcny.org/research/everybodys-doing-it.

- For more information on City health insurance and a comparison with the private sector, see: Maria Doulis, Everybody’s Doing It: Health Insurance Premium-Sharing by Employees and Retirees in the Public and Private Sectors, Citizens Budget Commission (January 27, 2013), https://cbcny.org/research/everybodys-doing-it.

- In addition, more than 75 percent of private sector employees in New York State are in plans with deductibles; the average deductible is $1,554 for single coverage and $2,888 for family coverage.

- For reference, in New York State in 2018, the private sector average single premium was $7,741 and the private sector average family premium was $21,904. Source: City of New York, Office of Labor Relations, email to Citizens Budget Commission staff (August 29, 2020); and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Insurance Component 2018 Chartbook (September 2019), https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/cb23/cb23.pdf.

- Contribution is based on employee salary grade. Salary schedules differ among unions; the salary range for the grade 9 job is between $37,966 and $47,051. See: State of New York, Governor’s Office of Employee Relations, “Salary Schedules” (accessed August 18,2020), https://goer.ny.gov/salary-schedules; and State of New York, Department of Civil Service, NYSHIP Rates and Deadlines for 2020 (November 2019); https://www.cs.ny.gov/employee-benefits/nyship/shared/publications/rates/2020/ny-active-unratified-rates-2020.pdf.

- Some unions, such as the United Federation of Teachers, now require 15 years.

- New York City’s long-term liability for retiree health and welfare benefits, referred to as other postemployment benefits or OPEB, is estimated to be $105 billion. See: City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Adopted Fiscal Year 2021 Budget: Supporting Schedules (July 2, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/ss6-20.pdf; and Office of the New York City Comptroller, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2019 (October 31, 2019), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/CAFR2019.pdf

- The lowest rate is for Medicare enrollees with income below $85,000 if single or below $170,000 for married couples; 94 percent of City retirees are below those thresholds and pay $1,735 per enrollee in Medicare Part B premiums. See: New York City Independent Budget Office, Savings Options: Lowering Wage and Benefit Costs of City Employees (December 28, 2018), https://ibo.nyc.ny.us/cgi-park3/2018/12/28/savings-options-lowering-wage-and-benefit-costs-of-city-employees/.

- Medicare supplemental policies or Medigap plans cover expenses and services not covered by Medicare, which can include deductibles, coinsurance or copays. For information on plans offered to NYC retirees, see: City of New York, Office of Labor Relations, New York City: Summary Program Description (SPD) Health Benefits Program (June 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/olr/downloads/pdf/health/health-full-spd.pdf.

- Mariana Alexander, Union-Administered Benefit Funds: Getting More Out of a Billion Dollar Taxpayer Contribution, Citizens Budget Commission, (February 8, 2018), https://cbcny.org/research/union-administered-benefit-funds; and Office of the New York City Comptroller, Analysis of the Financial and Operating Practices of Union-Administered Benefit Funds with Fiscal Years Ending in Calendar Year 2017 (November 15, 2019), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/SR19-086S.pdf.

- Mariana Alexander, Union-Administered Benefit Funds: Getting More Out of a Billion Dollar Taxpayer Contribution (February 8, 2018), https://cbcny.org/research/union-administered-benefit-funds; and Citizens Budget Commission, Better Benefits From Our Billion Bucks: The Case for Reforming Municipal Union Welfare Funds (August 2010), https://cbcny.org/research/union-administered-benefit-funds.

- The estimated savings from pharmaceutical benefits and other benefits are $98.6 million and $49.3 million, respectively. See: Mariana Alexander, Union-Administered Benefit Funds: Getting More Out of a Billion Dollar Taxpayer Contribution (February 8, 2018), https://cbcny.org/research/union-administered-benefit-funds.

- For discussion and description of the program, see: John Breit, Charles Brecher, and Maria Doulis, An Expensive and Risky Benefit: How Low Interest Rates Cost New York City Taxpayers $1.2 Billion Annually (October 5, 2016), https://cbcny.org/research/expensive-and-risky-benefit.

- In the long run, the TDA assets should be transferred to the Office of Labor Relations, which manages Deferred Compensation Plans for all other City employees.

- City of New York, Office of Payroll Administration, “Frequently Asked Questions About Pay” (accessed August 2, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/site/opa/my-pay/pay-frequently-asked-questions.page.

- All other employees average 59 hours of overtime for about $2,500. Source: CBC analysis of City of New York Open Data, Payroll (Fiscal Year) (accessed September 19, 2019), https://data.cityofnewyork.us/City-Government/Citywide-Payroll-Data-Fiscal-Year-/k397-673e.

- Jurisdiction of work is often a point of contention, and sometimes arbitrators determine that pay should be increased when a lower-paid title’s responsibilities overlap with that in a higher-paid title. Reconfiguring titles and labor-management agreement to allow for job duty expansion would allow for the most flexible and efficient allocation of labor.

- Ana Champeny, “Absent Teacher Reserve Costs $136 Million and Needs Reform,” Citizens Budget Commission Blog (June 14, 2018), https://cbcny.org/research/absent-teacher-reserve-costs-136-million-and-needs-reform.

- In fiscal year 2014 942 paramedics worked a total of 212,520 hours of overtime. In fiscal year 2019 that had increased to 317,516 hours worked by 845 paramedics. The decrease in the number of paramedics may be a factor, but even in fiscal year 2017, where there were 964 paramedics employed, overtime hours had increase by 23 percent since fiscal year 2014 to 262,109 hours. Source: CBC analysis of City of New York Open Data, Payroll (Fiscal Year) (accessed September 19, 2019), https://data.cityofnewyork.us/City-Government/Citywide-Payroll-Data-Fiscal-Year-/k397-673e.

- In fact, there are only five sanitation workers still employed at DSNY who started prior to the switch to two-person trucks. Source: CBC analysis of City of New York Open Data, Payroll (Fiscal Year) (accessed September 19, 2019), https://data.cityofnewyork.us/City-Government/Citywide-Payroll-Data-Fiscal-Year-/k397-673e.

- Exact language from the agreement letter is “if the tons per truck shift targets for a given district are unmet, the combined differential shall be paid provided that the District has met its targeted number of truck shifts and the new routes, designed to achieve a citywide average rate of 10.7 tons per truck shift for refuse and 6.2 tons per truck shift for recycling have been completed." See: City of New York, Office of Labor Relations, Executed Contract: Sanitation Workers (May 20, 2009), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/olr/downloads/pdf/collectivebargaining/cbu49-sanitation-workers-030207-to-092011.pdf.