Testimony Before the MTA Reinvention Commission

Thank you for the opportunity to share the Citizens Budget Commission’s (CBC) thoughts on improving the performance, or in the phrase Governor Andrew Cuomo has borrowed from David Osborne, on the “reinventing” of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). CBC has become increasingly concerned with the MTA’s finances and service performance over the last decade and most recently issued a report, A Better Way to Pay for the MTA, in October 2012. The CBC Board believes strongly that a well-financed and well-functioning mass transit system is a vital element in the regional economy, and a failure to support and enhance that system can be economically fatal. Based on our research, my testimony today stresses the theme that any “reinvention” at the MTA should focus on making sure the agency does a few basic but important things right.

Here are seven basic features of a “reinvented” MTA that are essential to the region’s future vitality and yet are not currently characteristic of the organization.

-

It has a balanced budget.

The MTA Board budgets on a cash basis rather than in accord with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). This enables it to meet its cash needs, but it leaves the agency with serious long-term fiscal problems. A reinvented MTA should balance its budget on a GAAP basis.

The major difference between GAAP and cash budgeting is that cash budgets do not provide resources for two substantial non-cash expenditures – depreciation and Other Post-Employment Benefits (OPEB). Depreciation is the “wear and tear” on physical assets that reduces their value; failure to fund depreciation obliges an entity to borrow to meet the capital needs associated with regular repair and replacement. OPEB refers to the present value of the future obligations an organization incurs in the form of promises to pay future benefits (notably health insurance) to current employees when they retiree; failure to fund OPEB obligations (like failure to fund pension obligations) leaves an organization vulnerable to large future payments that can be a debilitating drain on its resources.

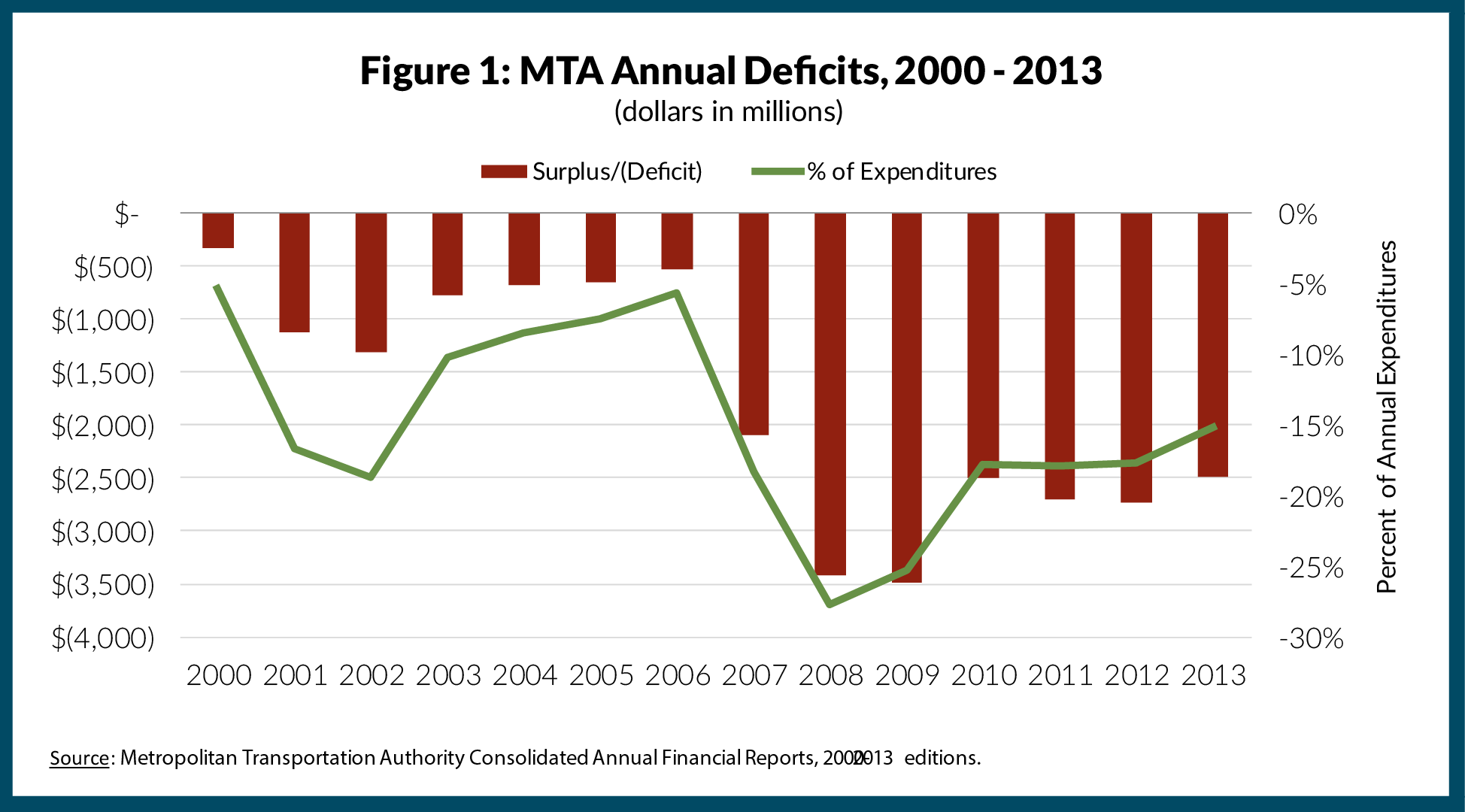

From 2000 to 2006 the GAAP-based annual deficits at the MTA ranged between $332 million and $1.3 billion; in 2007, when OPEB obligations were first required to be reported, the deficit jumped to $2.1 billion and increased in subsequent years. (See Figure 1.) Deficits since 2010 have been reduced due to authorization of the new Payroll Mobility Tax raising revenues of more than $1.3 billion annually.

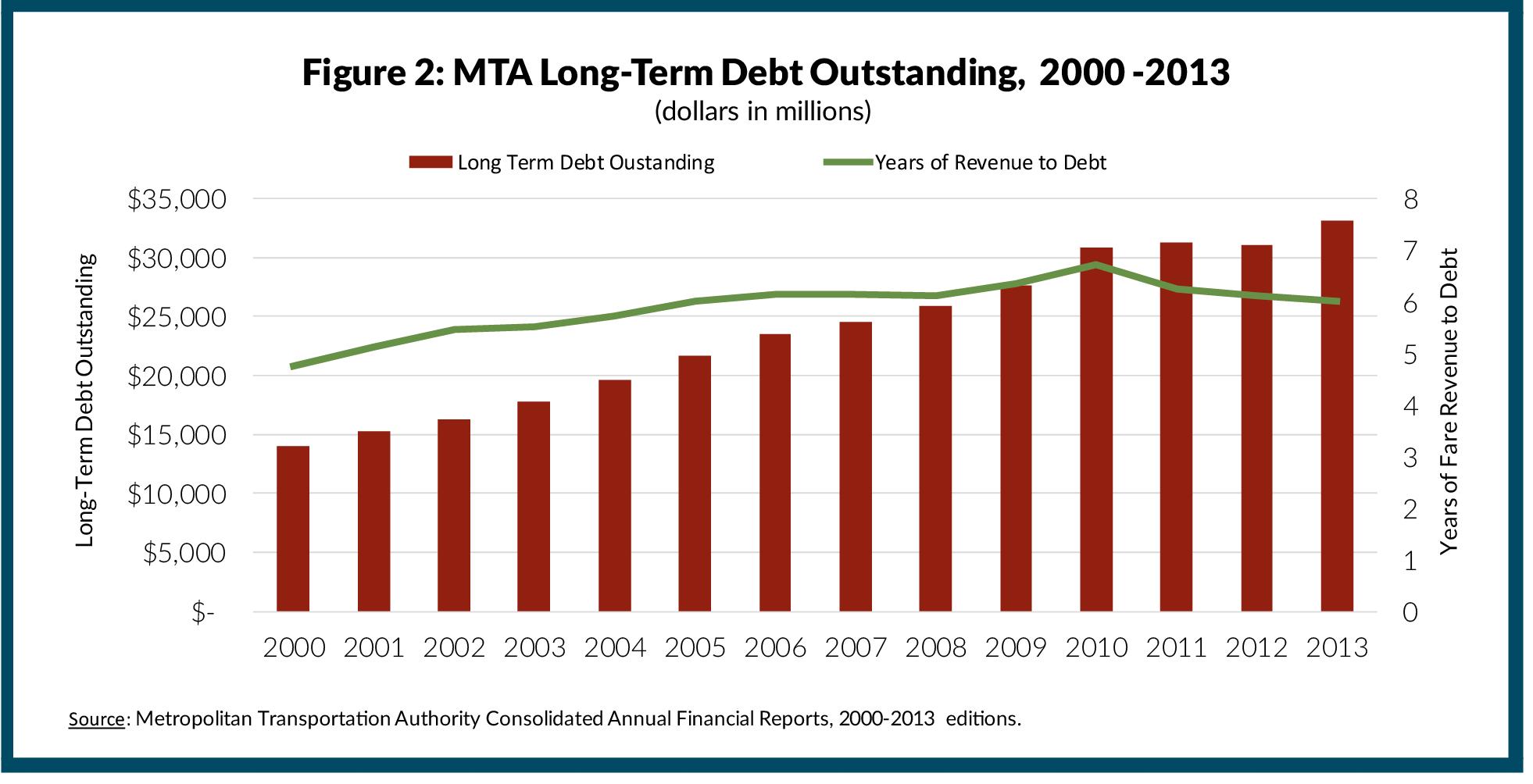

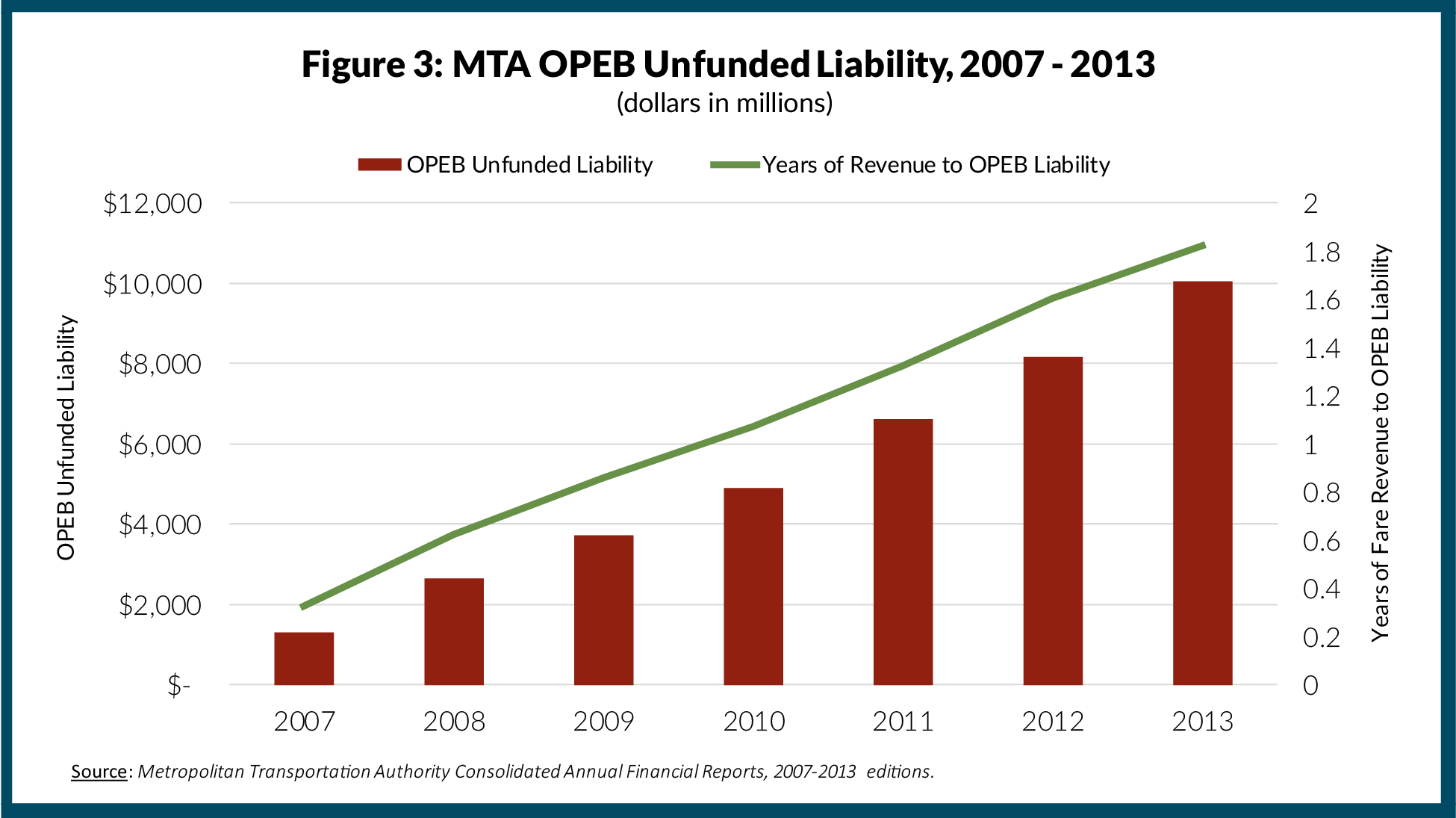

The consequences of the large, recurring deficit are: (1) large amounts of long-term debt, much of which is used to pay for repairs and replacements of assets that would be covered by operating revenues if the budget was balanced in accord with GAAP, and (2) a large and growing unfunded OPEB obligation that is a threat to the MTA’s future fiscal viability. As shown in Figure 2, The MTA’s long-term debt outstanding grew from $14 billon in 2000 to $33 billion in 2013. As shown in Figure 3 the MTA’s unfunded OPEB liability was $1.3 billion when first reported in 2007 and was $10 billion at the end of 2013.

-

It receives adequate revenues raised in an equitable manner.

A balanced budget requires revenues adequate to achieve that goal. The MTA does not now receive revenues sufficient for GAAP balance.

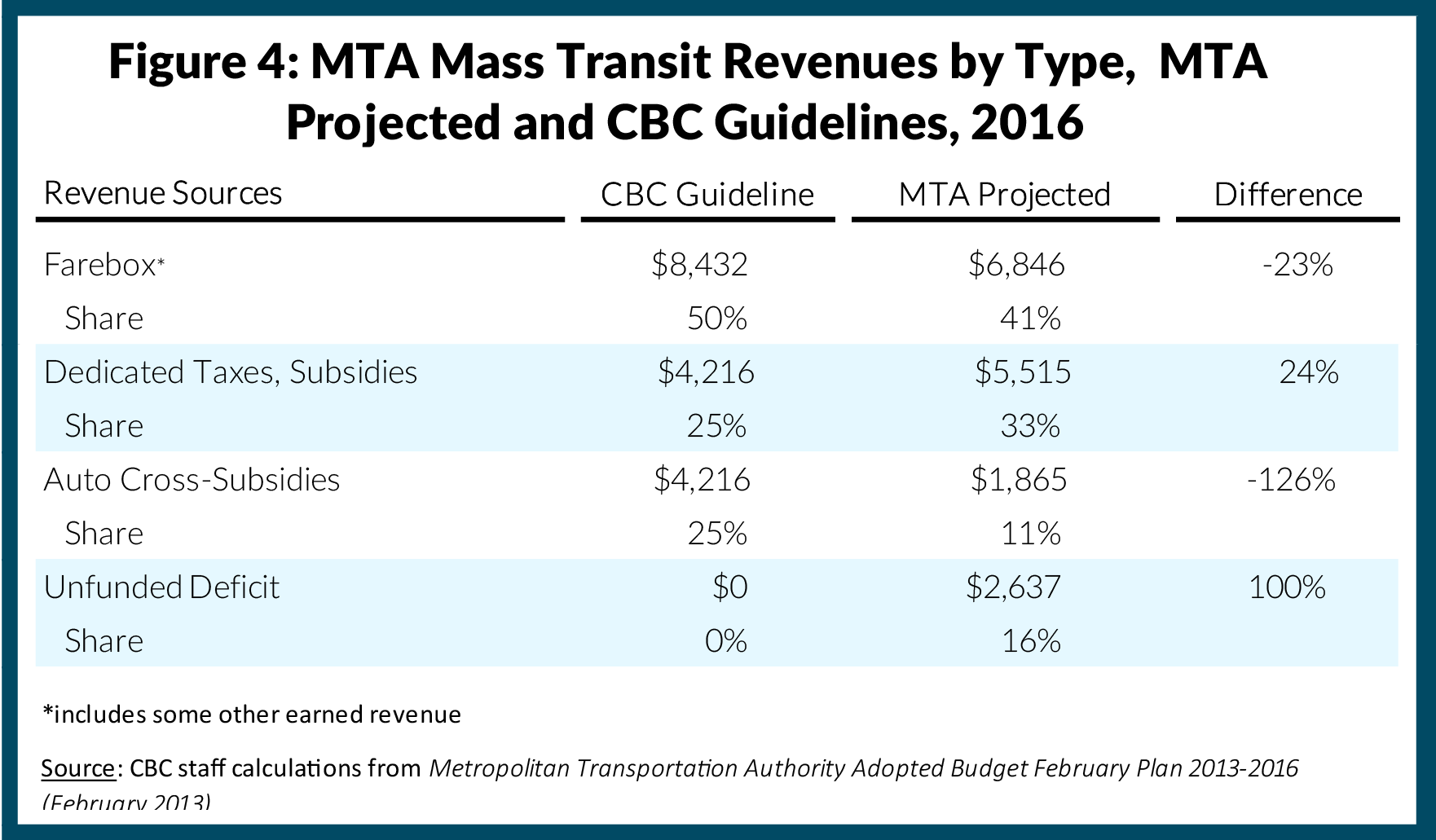

What is an equitable manner to raise these larger sums? CBC has recommended a “50- 25-25” strategy summarized as follows:

- Auto user fees should pay for the facilities available to drivers. Therefore, the cost of bridge and tunnel facilities should be funded entirely through tolls and fees paid by the motorists who use them.

- Motorists’ tolls and fees should also generate a surplus large enough to cover approximately one-quarter of the cost of providing mass transit services. The cross subsidy is justified by the need to compensate for the negative effects of auto use on the environment and the benefits to drivers from the reduced road congestion made possible by mass transit.

- Mass transit users should pay fares sufficient to cover approximately one-half the operating cost of those services. Riders get a direct benefit, and it is reasonable that they should pay a significant portion of the costs.

- State and local tax subsidies to mass transit should cover at least one-quarter of the operating cost of those services and fund “catch-up” capital investments needed to bring the system to a state of good repair. The subsidy is justified by the broad economic benefits to employers, workers, and shoppers provided by an efficient mass transit system.

The MTA follows the first guideline, but deviates from the other three. Not only are its revenues inadequate to balance the budget, they also rely too much on tax subsides and too little on fares, and most importantly, far too little on a cross subsidy from auto users. Figure 4 contrasts the budgeted MTA revenues for mass transit services (the selfsupporting bridges and tunnels are excluded) in 2106 with those derived by following the CBC guidelines. While tax subsidies are adequate, the fare revenue falls short by about 18 percent and the auto cross subsidy is less than half of what is needed.

Reasonable individuals can differ over whether the shares recommended by CBC comprise the best definition of equity, with some (including at least one member of the Reinvention Commission) believing the fare proportion is too high and the tax share too low. In any event, a reinvented MTA should have explicit policies for how it seeks to raise adequate revenues; the share from auto users should be significantly higher than is now the case, and fare increases should be more predictable and incremental than has been the case.

-

It conducts labor relations under a legal framework that balances the interests of labor and management and protects the interests of consumers.

The MTA has about 68,000 employees and about 60 percent of its total expenditures are devoted to compensating those workers. A well-functioning human resource system is essential for a well-functioning MTA.

The looming strike by Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) workers is a symptom of the lack of such a system at the MTA. The fault is primarily due to the inconsistent legal framework for labor relations with a mix of federal and state laws setting standards and procedures for different parts of the organization. State law governs the subway and bus workers, who are legally prohibited from striking and have available compulsory arbitration; federal law governs the commuter railroad workers, who are permitted to strike and do not have compulsory arbitration. In addition, the two commuter railroads have different unions and different pension systems, making integration of services very difficult. Compounding the problem is the unsatisfactory experience with both the state and federal systems; there have been subway strikes, all categories of workers receive fringe benefits more generous than those typically available in the private sector, and the different categories of MTA employees have disparities in work rules and compensation levels.

A reinvented MTA would have a legal framework for labor relations that permits all its employees to bargain under the same set of rules and be part of a single human resource system; the new framework would effectively prohibit strikes and provide timely binding arbitration that gives adequate recognition to standards of ability to pay without unreasonable tax or fare increases.

-

It achieves and sustains a state of good repair for its physical assets.

The MTA’s extensive and essential physical assets are not in a state of good repair (SOGR), and the agency does not have a plan for achieving a system-wide SOGR. The needs assessment prepared by the MTA in late 2013 categorized the subway and bus (New York City Transit or NYCT) assets into 15 different categories (such as subway cars, tracks, signals, traction power, and shops and yards) and indicated that only two of those categories of assets (subway cars and tracks) were in SOGR. All other categories had repair or replacement needs including such vital but nearly invisible features as power stations, ventilation fans, and water pumps that had serious deficiencies. This is the case despite capital investments totaling more than $115 billion system-wide since 1982. Moreover, the plan of investment identified by the MTA would invest another $106 billion system-wide including $68 billion for NYCT in the next 20 years yet leave many infrastructure components still not in SOGR. Similarly, although less severe, deficiencies exist and will persist at the commuter railroads.

A reinvented MTA would have a timely plan for bringing its assets to SOGR and would give highest priority in its capital investments to achieving that goal.

-

It uses proven technology to operate its fleet efficiently, safely and with good customer information.

The MTA operates most of its subway network with obsolete signal and communication systems. With just one exception, its subway lines all depend on decades-old electromechanical “block” signal and switching equipment. The well established state of the art technology deployed in multiple systems of similar scale around the globe is Communication Based Train Control (CBTC); it uses proven computer technology to permit safer and more efficient operations with lower maintenance costs.

The MTA has been slow to convert to CBTC. It deployed the technology on one line (the L line), requiring 10 years from 1999 to 2009 to make the change, and still has not achieved all the efficiencies the system makes possible such as single person and driverless operation. Conversion of a second line (the 7 line) began in 2010 and is planned for completion in 2017. The recent MTA needs assessment continues a slow pace of conversion with about half the subway network converted by 2034 and full conversion not likely until after 2050.

A reinvented MTA would make the financial investment and operational changes necessary for far speedier conversion to CBTC. A recent study by the Regional Plan Association recommends an alternative schedule that assigns priority to subway lines based on their age, capacity, and anticipated ridership growth and converts a much larger share of the system by 2034 than the MTA now contemplates.

-

It utilizes a fare collection system that is efficient, flexible, and easy for riders to use.

In 1994 the MTA began replacing its outmoded tokens with the MetroCard as a way to collect fares. The change was a dramatic improvement, and in 2000 CBC gave the MTA its annual Innovation Prize for the transformation. But the MetroCard system is projected to reach the end of its useful life in 2019, and more sophisticated fare collection methods have been developed and deployed in other mass transit systems around the nation and the globe. It is time for the MetroCard to go the way of the token. But the MTA has not yet been able to decide on a replacement system, and deferral of investment in a new system may lead to excessive maintenance expenses as well as foregone benefits for passengers.

A reinvented MTA would quickly initiate planning and deployment of a new fare collection system that reduces collection costs (currently estimated at 15 percent), permits flexibility in future fares such as zoned fares and peak pricing, and speeds passenger flow into the system.

-

It coordinates effectively with other transportation agencies to meet priority regional needs.

While the MTA is the largest transportation agency in the region, it is not the only important one. An efficient region-wide network requires coordination with New York State and New York City Transportation Departments, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, New Jersey Transit, and Amtrak. No mechanism exists to achieve this coordination; the federally mandated metropolitan planning organization, the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council, does not include New Jersey agencies and has little effective enforcement power.

Arguably the most significant transportation shortcoming in the region is trans-Hudson crossings, with Pennsylvania Station being a major bottleneck. The limited number of platforms at the station not only creates congestion for commuters arriving and departing, it limits the capacity for service for all modes relying on the station – the Long Island Rail Road, MetroNorth, Amtrak, New Jersey Transit, and PATH.

A reinvented MTA would take the lead in working with the other major regional transportation agencies to develop a plan for expanded trans-Hudson rail capacity including new tunnels and greater platform capacity at or near Pennsylvania Station. Such enhancements would not only increase inflow from New Jersey, it would also make possible increased service to the West Side of Manhattan by MetroNorth and the LIRR.

I recognize that achieving all these changes is not fully within the authority of the MTA Board or the Governor. Some of the changes require state legislation, and some federal action. But your recommendations should include items to be pursued by MTA and State officials as advocates with federal officials and in collaboration with the state legislature. Equally important the items within the control of the MTA Board, such as capital plan priorities and fare policies, should be part of your commission’s “reinvention” message.