An Expensive Deal in Albany

The legislative package passed in Albany last week rejected some misguided and expensive proposals, including a tax credit for benefactors of private schools. Unfortunately, other expensive proposals were included, adding to current and future state expenses without providing offsetting savings or revenues.1

The new state obligations will be close to $1.5 billion annually and can be described in three parts. First are four relatively small programs - $8.4 million for the State Education Department to print more versions of state exams, $25 million to the Yonkers school district (following a similar “one-time” $28 million bailout last year), $19 million to address economic hardship in municipalities with fossil fuel plant closures, and $6 million for an anti-poverty initiative in Rochester. The latter three programs are funded with sweeps from dedicated funds and transfers from the New York State Energy and Research Development Agency and the New York Power Authority. Second is an increase in aid to nonpublic schools of $250 million. The additional aid is deemed “one-time” to settle outstanding liabilities, yet the aid is linked to state reimbursements for recurring expenses such as mandated testing and data collection. The funds are to be distributed over two years; calls for additional “one-time” funds will likely continue after then.

By far the largest part is a new property tax relief rebate program, which will cost $1.3 billion annually when fully implemented. In his Executive Budget this year, Governor Cuomo proposed a different version of property tax relief, claiming it would be funded with projected budget “surpluses.” However, achieving future surpluses depends on continued economic growth and limitations in overall state spending, neither of which is guaranteed.

Rebate Madness

Prior to last week’s agreement, New York State was set to spend $1.2 billion on two other rebate programs this fiscal year. At an annual cost of $410 million, the Family Tax Relief Rebate provides $350 to households with children under age 17 and annual income between $40,000 and $300,000; the Property Tax Freeze Rebate provides an amount equal to the annual increase in property taxes to homeowners earning less than $500,000 in tax cap-compliant local governments and school districts and costs $783 million annually. The Family Tax Relief Rebate is distributed through the state income tax and will apply to tax years 2015 and 2016, while the Property Tax Freeze Rebate is issued as a check. The latter is authorized for one more year and will be combined with the new rebate in 2016. It is unclear if the new rebate is intended as a replacement or a supplement.

Governor Cuomo proposed a “circuit breaker” personal income tax credit in his Executive Budget, which would have refunded a portion of a household’s property tax liability when it exceeded a predetermined share of income, in recognition of the regressive nature of property taxes. However, legislators rejected this approach.

The new property tax rebate is a slight improvement over the two existing rebates, but it is flawed in two important ways. First, it is limited in its applicability to households in certain parts of the state; New York City homeowners are excluded as are renters statewide. Second, its benefits are skewed to favor wealthier rather than poorer households because the amounts are linked to the School Tax Relief (STAR) program. STAR benefits are adjusted upward in counties with high home values, so the program disproportionately benefits wealthier households. For example, the maximum annual STAR savings in Babylon in Suffolk County is $1,359, while the savings is only $551 in Tonawanda in Erie County.2

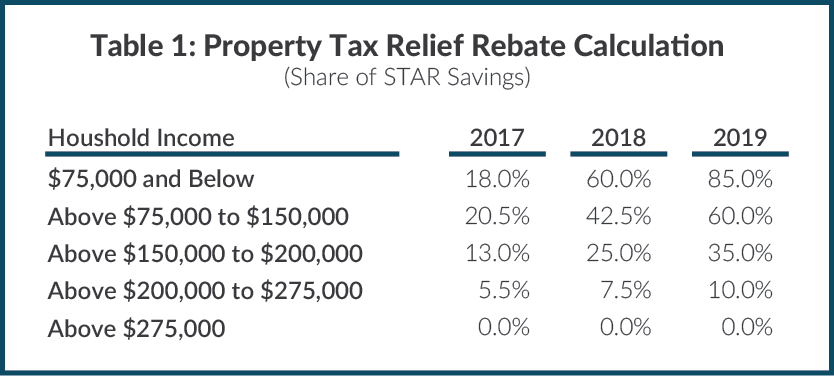

In 2016 the new rebate will be a flat $185 upstate and $130 in the downstate Metropolitan Commuter Transportation District, but in the next three years the rebate will be based on a graduated share of the homeowner’s STAR savings amount. By 2019 the shares would range from 10 percent to 85 percent for eligible households. (See Table 1.) Based on STAR savings amounts today, a homeowner in Babylon with income of $100,000 would receive a rebate of $279 in 2017, growing to $815 in 2019, while a homeowner with a similar income in Tonawanda would get $113 in 2017 and $331 in 2019. One positive feature of the new rebate is a requirement for the school district to be in compliance with the property tax cap, which will prevent local districts from raising the tax levy in response to the new rebate.

Abatements Rely Upon an Ongoing Surplus

This costly new tax rebate is predicated on the existence of a surplus in upcoming fiscal years. Prior to the legislation last week, New York State’s financial plan showed “surpluses” growing to $1.6 billion in fiscal year 2019, but these rely on unspecified future savings based on the assumption that annual spending growth will be held to 2 percent over the four-year period.3 While overall state spending growth in recent years has been held close to 2 percent annually, baseline spending is projected to outpace revenue growth over the next few years. In reality, prior to the new spending, New York State faced out-year budget gaps that grow from $2.0 billion next year to $4.2 billion in fiscal year 2018-2019.4

Constraining spending to a growth rate of 2 percent has become increasingly difficult. Over the past four years, school aid has grown at an average annual rate of 4.4 percent, while the Department of Health’s Medicaid program has increased 3.3 percent annually on average.5 To maintain overall growth of about 2 percent per year in total state spending, all other spending growth has been held to only 1.0 percent per year on average.

Dealmaking in Albany is often expensive, and this year was no different. Lawmakers must now be prepared to enact cost-saving measures to produce the “surpluses” they just spent.

Footnotes

- In addition to the impact on the state budget, the agreement will constrain future tax revenues for New York City by expanding the 421a program and extending business tax breaks for Lower Manhattan. However, lawmakers rejected a costly proposal for disability benefits for New York City police and firefighters.

- New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, “School District’s 2015-2016 STAR Savings by Municipality or School District” (accessed June 26, 2015), www.tax.ny.gov/pit/property/star/max_index.htm.

- New York State Division of the Budget, FY 2016 Enacted Budget Financial Plan (May 2015), http://publications.budget.ny.gov/budgetFP/FY16FinPlan.pdf.

- For more information on the New York State budget gaps, see Rachel Bardin and Tammy Gamerman, Citizens Budget Commission, “New York City and New York State Budget Briefing” (presentation, June 23, 2015), Slide 15.

- Total spending for fiscal year 2016 was adjusted upward by $953 million for debt service prepayments that occurred in fiscal year 2015 and adjusted downward by $100 million for anticipated debt service prepayments for fiscal year 2017 obligations. CBC staff analysis of New York State Division of Budget, FY 2016 Enacted Budget Financial Plan (May 2015), http://publications.budget.ny.gov/budgetFP/FY16FinPlan.pdf.