Federal Aid Now, Fiscal Cliffs Later

The Missed Opportunity for NYC Budget Stability

New York City’s infusion of COVID-19 federal aid from already passed legislation is expected to reach $22.3 billion. While the City budget previously had included $6.6 billion of this aid, the Fiscal Year 2022 Executive Budget added another $15.7 billion. The new funds, primarily from the recently enacted American Rescue Plan (ARP), help the City meet a variety of important needs in the near term. However, the City’s planned uses fail to leverage the federal aid to help stabilize the City’s long-term fiscal position and in fact worsen it by widening out-year budget gaps.

Prior to the release of the Executive Budget, the Citizens Budget Commission (CBC) recommended that the City employ four strategies to cross the bridge to fiscal stability. In addition to ensuring quality services, rightsizing the budget and workforce, and increasing reserves, it is essential the City use federal aid wisely: spread over time as a restructuring runway, provide targeted relief, support recovery, restore service cuts if necessary, and offset revenue shortfalls, while not supporting recurring programs that lack future alternative funding.

The Executive Budget’s plan for federal funds does spread some of the funds over time and supports relief and recovery programs. However, it falls dramatically short of the CBC recommendation by funding recurring programs. The plan funds at least $1.3 billion in annual recurring programs, and another $2.7 billion in programs that are possibly recurring since the desire and demand for them will not necessarily wane as the federal support ends. Based on CBC’s analysis, this leaves a hidden fiscal year 2025 budget gap of between $213 million and $2.6 billion, and a fiscal cliff as high as $4 billion in fiscal year 2026 when federal aid is depleted.

Furthermore, the information currently available lacks the specificity needed a) to know what some of the programs funded will do, and b) to evaluate these programs’ potential value, leaving unanswered the question whether the Administration’s planned spending—what it terms “investments”—will predictably yield commensurate future benefits. Greater detail is needed to address these shortcomings and facilitate the transparency and accountability that should accompany this historic level of resources and the opportunity they provide.

Evaluating the planned use of new COVID-related federal aid, CBC finds that:

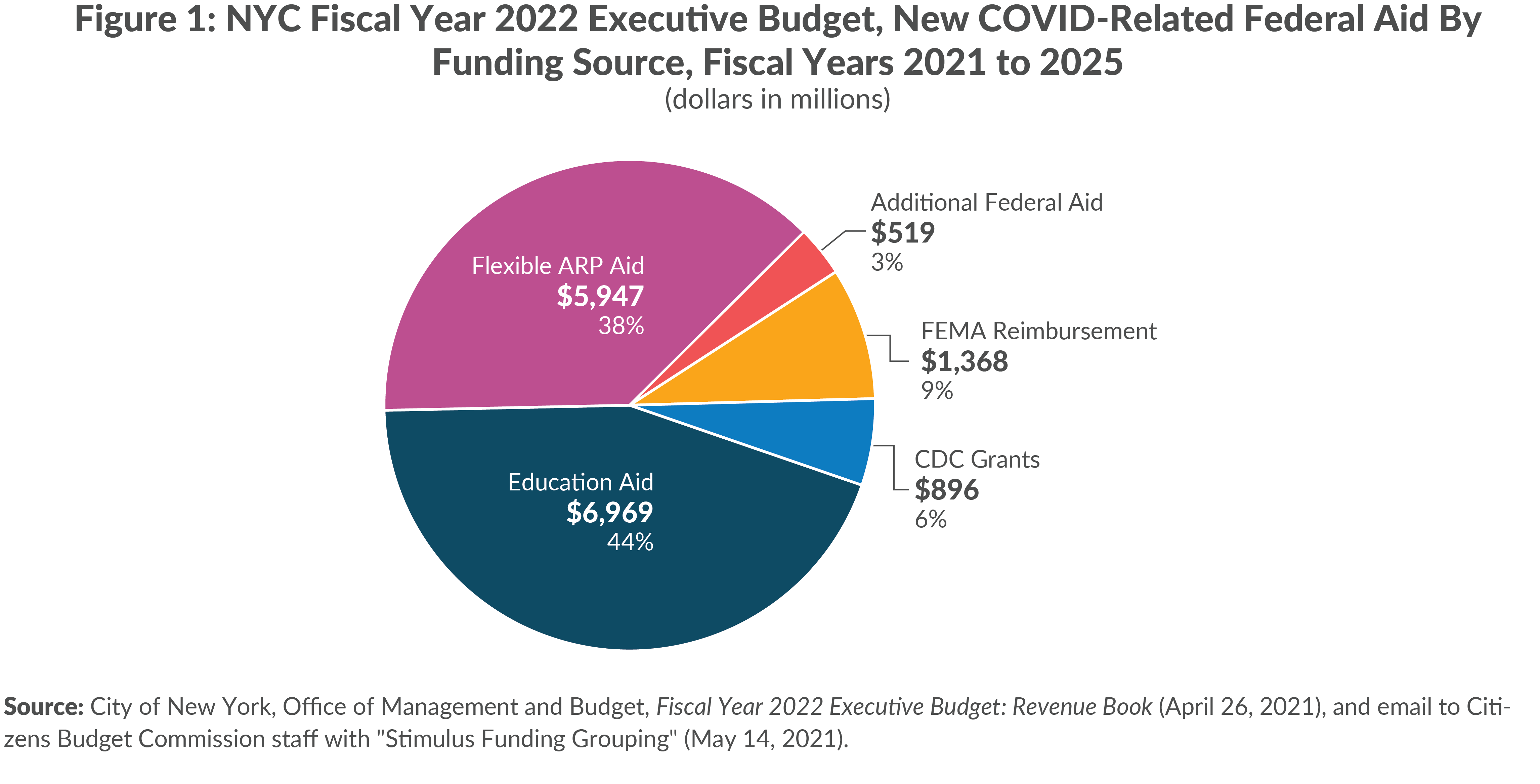

- Newly budgeted federal aid is comprised of flexible ARP aid ($5.9 billion), ARP education aid ($7 billion), Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) reimbursement ($1.4 billion), previously unbudgeted Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act funds ($520 million), and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) grants ($900 million);

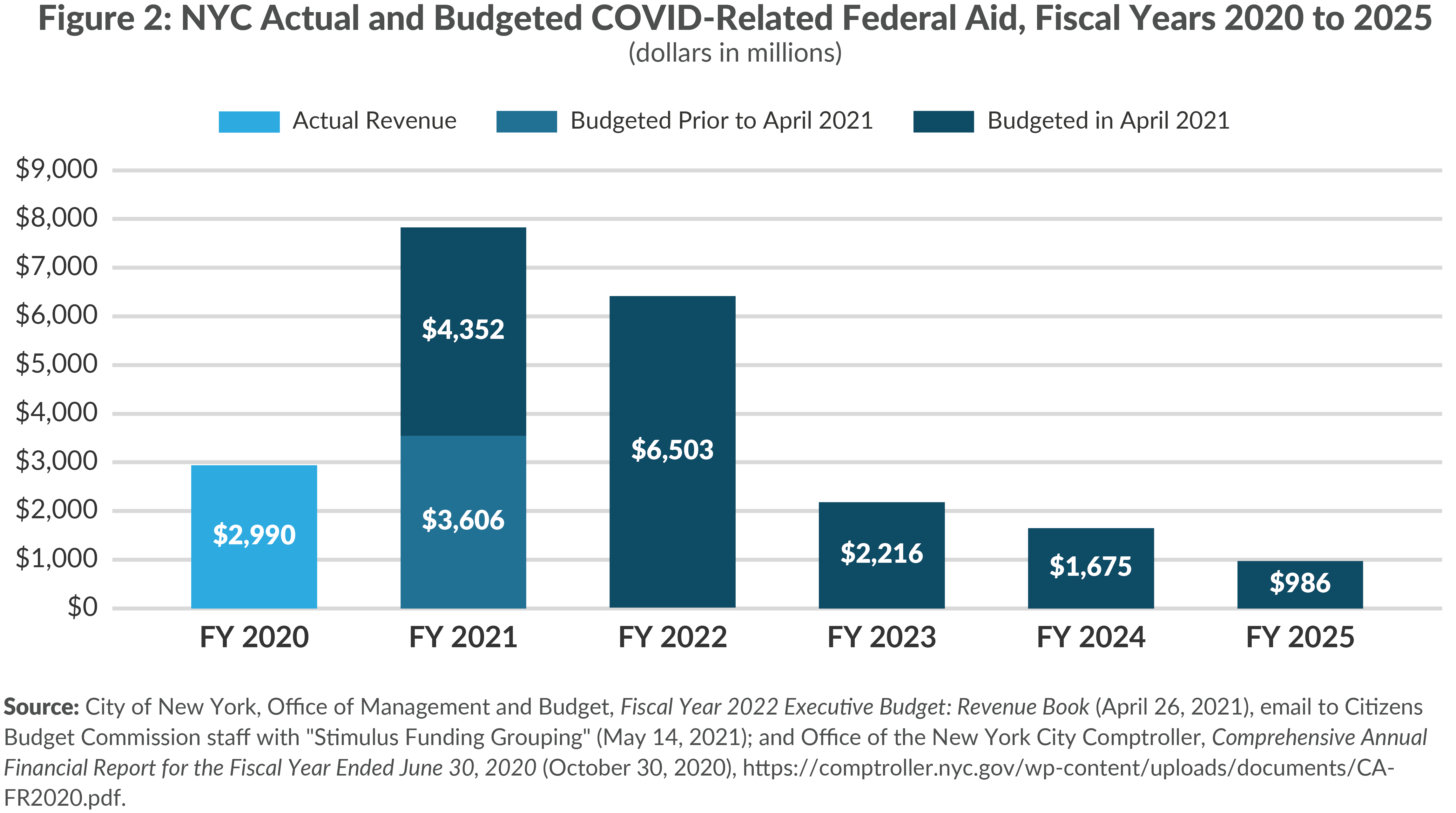

- New federal funds are front-loaded, with two-thirds ($9.5 billion) spent by the end of fiscal year 2022 and just 12 percent left for fiscal year 2024 and 7 percent for fiscal year 2025;1

- Nearly half of the new aid ($7.6 billion) supports initiatives in the Department of Education (DOE), but $3.1 billion of that lacks sufficient detail to determine how the funds will be used and what value they will provide;

- Flexible ARP federal aid is split relatively evenly between fiscal relief (e.g., eliminating two years of unspecified labor savings, swapping City funding for COVID-related personnel leaves) and programs (e.g., pandemic response such as test and trace, recovery including summer youth programs and small business relief, and a large number of programmatic initiatives including the expansion of right to counsel);

- Funds are spread among many initiatives, some of which appear of questionable value or should be supported sustainably with City funds, including the Clean Up Corps ($250 million) that largely replicates existing agency duties, attrition restoration ($149 million) that reverses a prudent reduction in the City’s workforce, and nonprofit indirect rate funding ($61 million annually) which is a recurring expense;

- Federal aid is used to support at least $1.3 billion annually in recurring programs and another $2.7 billion of potentially recurring programs, leaving a looming fiscal cliff as high as $4.0 billion in fiscal year 2026;2

- Funding for recurring programs peaks in fiscal year 2024 at $1.3 billion; maintaining these programs would require City funding of $213 million in fiscal year 2025 and $1.3 billion in fiscal year 2026;

- Another $2.7 billion annually at peak value supports potentially recurring programs—programs that once started may be expected to continue—including mental health teams, housing vouchers, and programs for which insufficient detail is available; maintaining these programs at their peak funding would require $2.4 billion in fiscal year 2025 and $2.7 billion in fiscal year 2026; and

- The fiscal cliff is particularly a concern for DOE, which receives nearly $3.5 billion of the $4 billion recurring and potentially recurring programs, including $753 million for the expansion of 3K (early childhood education for 3-year-old children).

While the City’s proposed plan supports many significant relief and recovery needs, using aid to fund recurring programs and spreading it thin among many initiatives and restorations that may not be of significant value fails to take this historic opportunity to restructure City finances for long term stability. The pandemic and recession have created and laid bare substantial needs and inequities. The City is receiving a great deal of federal aid that should be spent to address these. Rather than disperse funds across many programs, the City should ensure the funds are targeted to address the greatest needs most efficiently. The City also should take care to design and clearly communicate that the one-time relief and recovery initiatives will sunset.

In allocating federal aid in the adopted budget, the City should: ensure each program will provide needed benefits, modify the programs accordingly, and only fund ongoing programs if there is a specific plan to backfill federal funds with City resources in future years. These actions should be part of a comprehensive relief, recovery and stability budget that includes recurring efficiency-based savings programs to ensure fiscal sustainability, slowed but continued workforce reductions, and deposits to the Rainy Day Fund throughout the plan to be prepared better for the future.

COVID-Related Federal Aid to Exceed $22 Billion Between Fiscal Years 2020 and 2025

New York City currently expects federal COVID-related aid to reach $22.3 billion. The City received $3.0 billion in fiscal year 2020, primarily from FEMA and the Coronavirus Recovery Fund (CRF) established by the CARES Act. An additional $3.6 billion in FEMA and CARES funds were budgeted for fiscal year 2021 prior to the release of the Executive Budget. The Executive Budget recognizes an additional $15.7 billion in COVID-related federal aid and budgets it from fiscal year 2021 through fiscal year 2025.

New COVID-Related Federal Aid is Primarily for Education and Flexible Fiscal Support

The $15.7 billion added in the Executive Budget includes $7.0 billion in education aid from the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSA) and ARP, $5.9 billion in flexible aid from ARP, $519 million in other programmatic aid (mainly from CARES), $1.4 billion in reimbursement from FEMA, and $896 million from CDC grants authorized in various federal appropriations. (See Figure 1.)

Education Aid

New York City received $2.2 billion from CRRSA and $4.8 billion from ARP for elementary and secondary school costs as part of the school aid allocation from New York State.3

Flexible ARP Aid

The ARP allocated $155 billion to local governments for four uses: 1) support COVID-19 response efforts, 2) replace lost revenue, 3) support economic stabilization of households and businesses, and 4) address public health systems and economic challenges that contributed to the unequal impact of the pandemic.4 The City was allocated $5.9 billion.5

Other Federal Aid

The remaining $2.8 billion came from FEMA, CDC, and supplemental CARES funds.

- FEMA reimbursement of $1.4 billion is for expenditures associated with responding to the pandemic.6 At least $580 million of the additional FEMA funds are due to higher reimbursement for previously eligible expenses; other costs being reimbursed by FEMA are vaccination (about $350 million), homeless services (about $286 million), and food assistance (about $135 million);

- The City is receiving nearly $900 million in funding being allocated through two pre-existing CDC grants: Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity (ELC) and the Immunization Grant. The US Congress provided supplemental funding via these grants in multiple appropriations, including ARP, CARES, CRRSA, and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act.7 These funds primarily support Department of Health and Mental Hygiene programs, as well as funding in the NYC Health + Hospitals (NYC H+H) budget for certain school reopening costs; and

-

The City recognized an additional $519 million primarily from the CARES CRF. The budget provides little information on the use of these funds.

New COVID-Related Federal Aid is Front-Loaded

Two-thirds of the new COVID-related federal funds are used in fiscal years 2021 and 2022 (21 percent and 45 percent, respectively). (See Figure 2.) The federal funds then phase out over the next three years, from 14 percent in fiscal year 2023 to 12 percent in fiscal year 2024 to just 7 percent in fiscal year 2025.

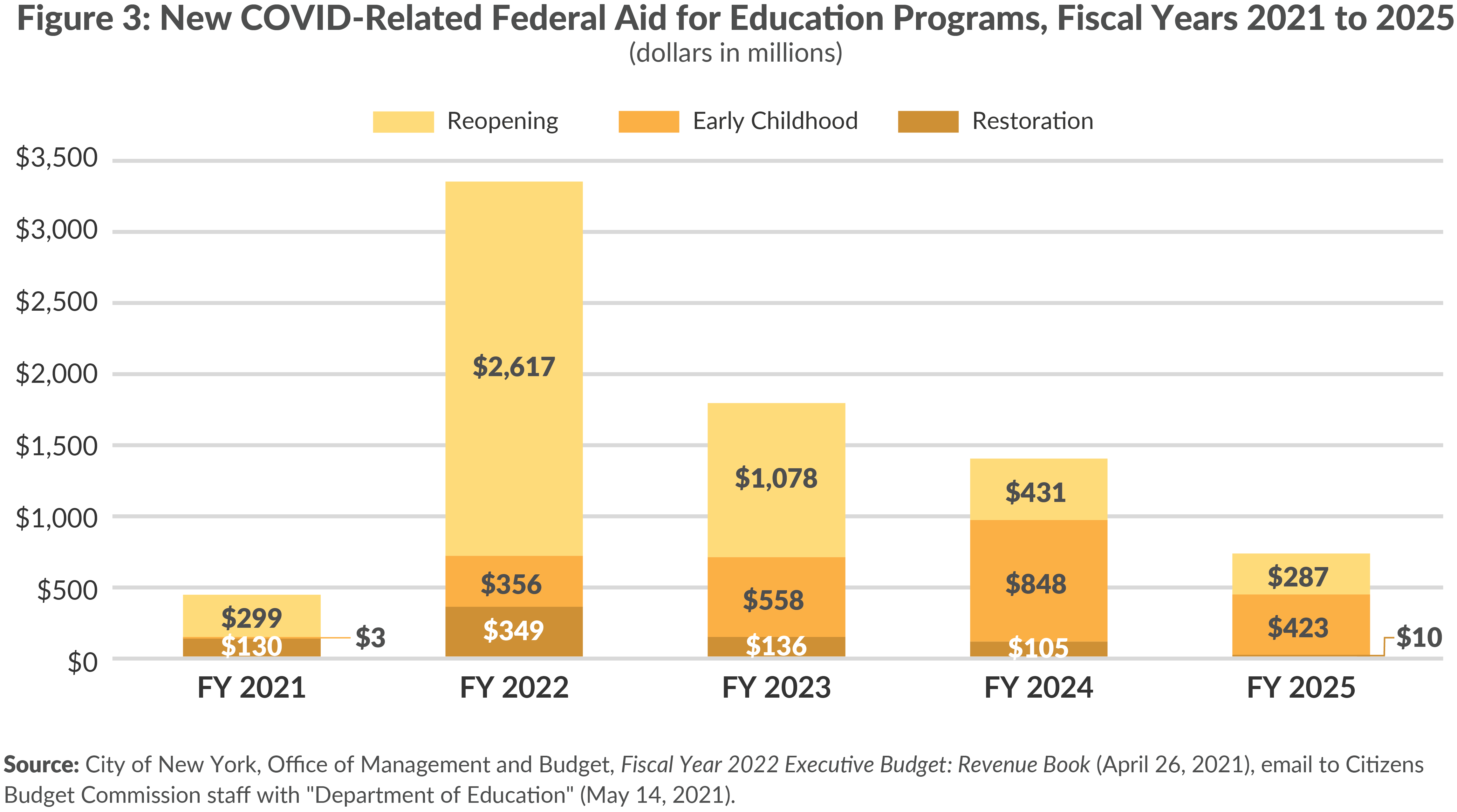

$7.6 Billion Will Fund Schools—Primarily Re-Opening and Early Childhood Expansion

Reopening schools and addressing substantial learning loss and social-emotional needs of the City’s students is of paramount importance to the City’s residents and economic recovery. In addition to the $7.0 billion in restricted education aid, the City plans to support schools with $375 million in flexible ARP aid, $251 million in CDC ELC grants from NYC H+H, and $35 million in CARES funding.

The support can be separated into three categories: elementary and secondary school reopening programs, early childhood education, and restoration of planned spending cuts. (See Figure 3 below and Appendix Table 1 for detailed program list.)

School Reopening

More than 60 percent of the funds—$4.7 billion—are dedicated to reopening the City’s elementary and secondary schools, addressing learning loss, and other student needs.

Sixty-five percent ($3.1 billion) of the school reopening funds are for four initiatives that are very broadly characterized: operational support ($1.4 billion), academic recovery and student supports ($850 million), instructional support ($532 million), and programmatic support ($308 million). The Executive Budget essentially phases-out these funding lines by fiscal year 2025 from a high of $2.0 billion in fiscal year 2022 to $277 million in fiscal year 2024. Given the lack of detail available, it is not possible to determine how the funds will be used and what value they will provide. Nevertheless, it is likely schools will want to continue some of the programs or support functions, which would require City funds currently not budgeted.

The City also is budgeting federal aid to fund mental health supports, expand community schools, expand public school athletic league (PSAL), and fund community schools’ sustainability—annually allocating $98 million, $145 million, $147 million, and $79 million from fiscal year 2022 through 2025, respectively. The City does not provide City funding to cover the decrease in fiscal year 2025 ($68 million) or identify a funding source for fiscal year 2026 and beyond.

Additionally, there is significant concern that students with disabilities, who make up nearly 20 percent of NYC public school students, have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic and remote learning. If it exists, an assessment of these students’ needs has not been made public. Currently, the City plans to use $176 million in fiscal year 2022 and $104 million in fiscal year 2023 to bolster special education funding.8

Early Childhood

The Administration is continuing its commitment to early childhood education, which receives 29 percent of the education aid. In addition to reversing a planned slowdown in the expansion of 3K, significant federal aid is being used to make 3K universal by fiscal year 2024. The 3K expansion would cost $334 million in fiscal year 2022, $470 million in fiscal year 2023, and $753 million in fiscal year 2024. In fiscal year 2025, the cost does not increase but is split between federal and City funding—$376 million each. Funding of the full $753 million for fiscal year 2026 and beyond is not identified.

The Administration also is putting $252 million toward expanding preschool special education programs, increasing the commitment from $22 million in fiscal year 2022 to $95 million in fiscal year 2024. Fiscal year 2025 is funded at half that level, with $47 million in federal funds. No additional City funds are provided in fiscal year 2025 to maintain the prior year level, so either service would have to be reduced or City funds would have to be added; no funding source is identified for fiscal year 2026.

Restorations

Fully $731 million over five years (10 percent) is used to restore planned budget reductions. About $400 million would restore non-recurring cuts, including those for school budgets and professional development. The remaining $324 million restores recurring programmatic cuts in fiscal years 2022 through 2024, including those to equity and excellence programs, arts education, and health education. These cuts likely were carried forward to fiscal year 2025 and beyond in the baseline budget and approximately $100 million in additional annual funding may be needed to continue the programs.9

Flexible ARP Aid Is Split Between Short-Term Fiscal Relief and New or Expanded Programs

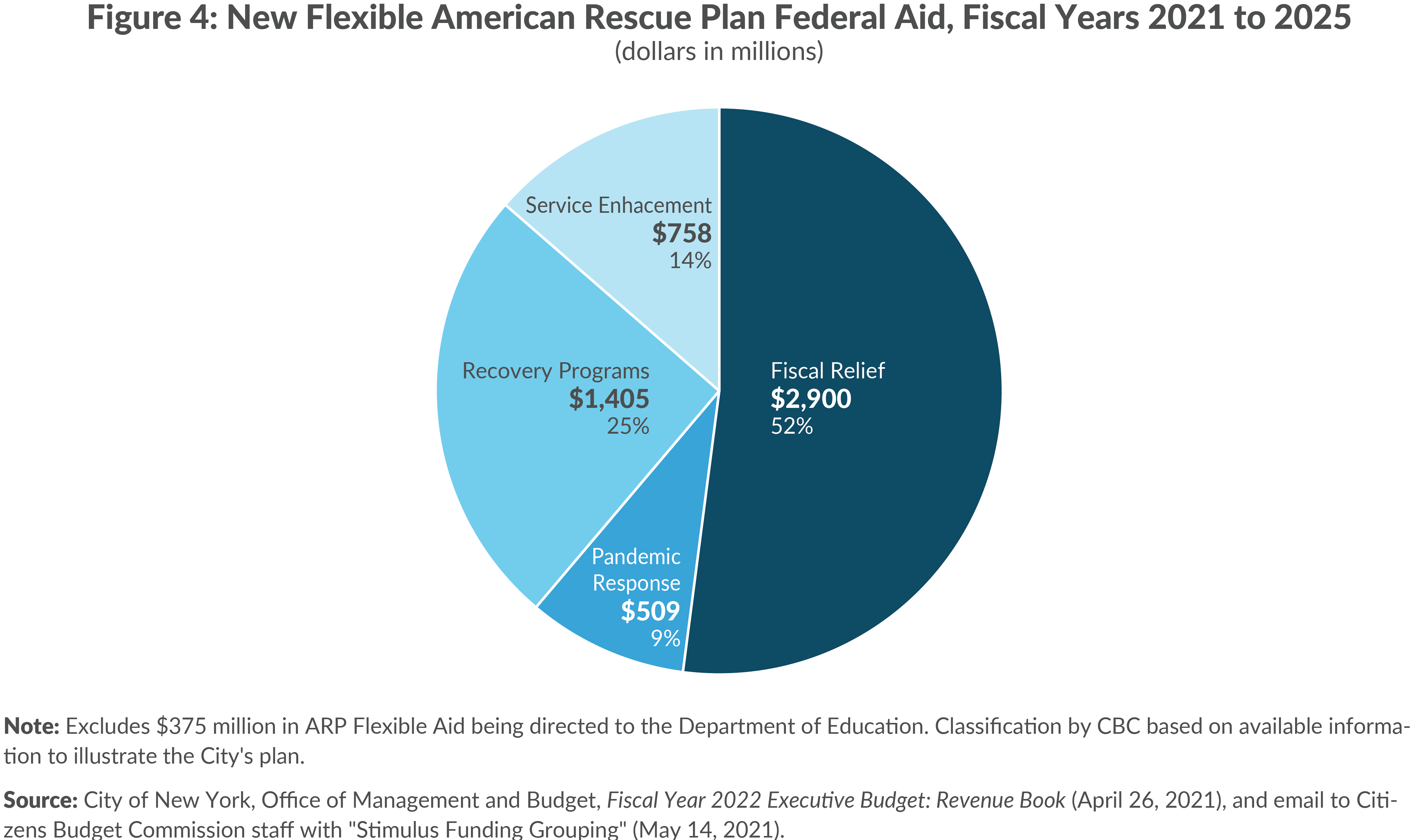

Of $5.6 billion in flexible ARP aid, excluding the $375 million directed to the DOE, the City is using more than half ($2.9 billion) to provide short-term fiscal relief, while the remainder funds an array of programs for COVID response, recovery, and service enhancement. (See Appendix Table 2 for full program list.)

The $2.9 billion in fiscal relief includes $1.3 billion to eliminate previously unspecified labor savings in fiscal years 2021 and 2022, $150 million to roll back planned headcount reductions, $504 million to swap City funding for COVID-19 related leaves from work, $500 million to fund the Department of Sanitation (DSNY), $280 million to fund the Department of Correction, and $346 million for other personal service costs and funding swaps. This fiscal relief is needed, in part, because the City has not mitigated revenue shortfalls by identifying and implementing efficiencies and reforms that would preserve services but lower costs, as CBC has advocated.

Fully $2.7 billion is directed toward programs that respond to the pandemic, support the recovery, or enhance City services. There is not necessarily a bright line distinction between these groups, but CBC categorized initiatives based on the available information to illustrate the City’s plan. (See Figure 4.)

- $509 million is for pandemic response, which includes $304 million for test and trace, $134 million for emergency food assistance, and $30 million to restore service reductions, primarily at the Department of Sanitation (DSNY).

- $1.4 billion supports programs that can be considered part of recovery. This includes $371 million for health and mental health programs, $329 million for housing vouchers, $179 million for small business loans and grants, $165 million for youth programs, and $133 million for senior services. Many recovery programs are one to two years in duration, which is appropriate given the aid is non-recurring. This is not always the case. Other programs may initially support the recovery but then transition into on-going City services, including about $236 million in recovery programs in fiscal years 2024 and 2025. For example, in fiscal year 2025, the City is using $48 million to support community care investments at senior centers, and $16 million to expand access to counsel in housing court; shrinking these programs once aid is depleted may have opponents.

- Service enhancement totals $747 million. Some might be funding important needs but their reliance on non-recurring federal aid is problematic; others may be of questionable value.

- For example, $306 million over five years to fund an increase in the nonprofit indirect rate may be good policy, but it is not a wise use of federal aid that will not be ongoing.

- Conversely, the Clean Up Corps ($250 million) may not provide significant value to relief or recovery, and it also appears to duplicate functions already provided by DSNY and other City agencies.

- Another $98 million supports 12 different initiatives, such as the Cultural Corps, Central Park Conservancy, Gowanus Canal clean-up, and creation of open spaces proposed in the Mayor’s State of the City speech.

In total, this $2.7 billion support 62 separate initiatives. Many are worthy and will provide valuable relief and recovery. However, disbursing the funds to many small programs raises the question of how well targeted they are and whether there is reasonable evidence that they will be effective.

Using Non-Recurring Federal Aid to Fund Recurring Programs Could Create a $4 Billion Fiscal Cliff

While new federal aid declines until depleted during fiscal year 2025, the substantial new and expanded programs funded are unlikely to end without opposition once the federal aid is exhausted. As a result, the proposed use of federal aid is likely to create a substantial fiscal cliff that could reach $4 billion in fiscal year 2026, when it is added to the financial plan in January 2022. (See Appendix Table 3 for full list of programs.)

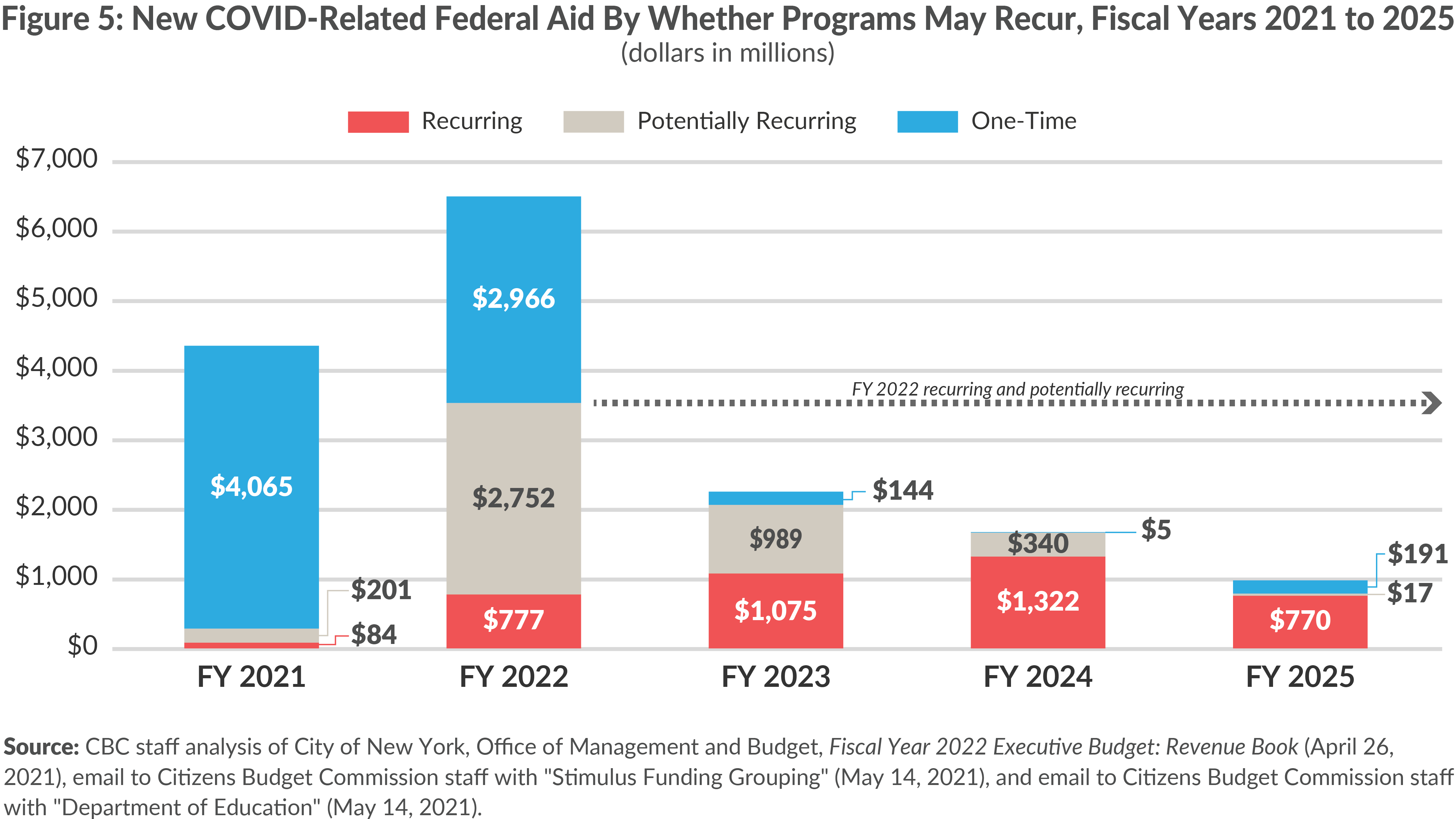

The City is dedicating substantial funding to programs that are expected to recur and will lack funding after the federal aid is depleted. (See Figure 5.) The peak level of federal funding for recurring programs is $1.3 billion in fiscal year 2024. In fiscal year 2025, with federal funds being depleted mid-year, many of these programs are funded at half their fiscal year 2024 level, with only a handful slated to receive City funding. The non-funded programs result in a hidden fiscal year 2025 budget gap of $213 million. For fiscal year 2026, the next Administration would need to identify at least $1.3 billion in new revenue to maintain these services.

Furthermore, many other services being funded will develop constituencies and expectations the programs continue beyond the federal funding. These “potentially recurring” programs (see Figure 5), include discrete programs like the mental health teams, Summer Rising summer educational program for K-8 students, and rental housing vouchers, as well as the substantial reopening funds for operational, instructional, and programmatic support flowing to DOE that phase-out rapidly. Together, these programs total $2.8 billion in fiscal year 2022 and nearly $1 billion in fiscal year 2023. If they all were to recur at their peaks, these would have funding gaps of $1.7 billion, $2.4 billion, and $2.7 billion in fiscal years 2023, 2024, and 2025, respectively.

Between the recurring and potentially recurring programs, there could be hidden budget gaps as early as fiscal year 2023, and a fiscal cliff reaching $4 billion in fiscal year 2026. Funding only those programs identified as recurring programs would require an additional $1.3 billion in fiscal year 2026. Continuing the potentially recurring programs as well would bring the total unfunded need to $4 billion in fiscal year 2026.

Conclusion

The City’s Executive Budget presents the Administration’s plan for nearly $16 billion in new COVID-related federal funding. Two-thirds of the funds are used in fiscal years 2021 and 2022 with more than $4 billion providing direct fiscal relief and restoration of prior budget cuts. However, a substantial portion of the funding, concentrated in education, supports new and expanded programs, which raises four concerns. First, there is insufficient information to reasonably understand the programmatic and funding choices and assess whether these are the most beneficial and effective uses. Second, in some cases where details are available, the Administration’s decisions raise questions because the programs are of insufficient value or would be better suited to City funding. Third, the use of funding for recurring and potentially recurring programs reveals hidden budget gaps in the financial plan and creates the risk of a significant fiscal cliff as federal funding runs out. Based on information available about the use of funds, the unfunded need in fiscal year 2026 could range from $1.3 billion for clearly recurring programs to $4.0 billion if potentially recurring funding is included. Fourth, the Administration has not provided sufficient detail on the programs and the results they are expected to achieve. To ensure the public has sufficient information with which to hold its government accountable, the City should commit to provide complete, detailed information with each financial plan on spending as was done following the Great Recession and Hurricane Sandy.

As the Administration and City Council move into budget negotiations, following CBC’s four strategies for crossing the bridge to fiscal stability would allow the City to provide relief, support recovery, restructure for sustainability over time, and be prepared for the future. Specifically, the City should reevaluate some of the planned use of the flexible ARP aid and shift those funds to higher value, non-recurring programs as needed. It also should provide greater detail on the $3.1 billion broadly defined DOE programs to ensure they are highest value and reevaluate whether the enhancement programs being funded with flexible ARP aid are necessary and suited to fund with federal aid. The Adopted Budget should include a PEG program equaling 2.5 percent of agency city funded spending that identifies recurring efficiency savings beginning in fiscal year 2022. These savings should be used to reduce the amount of federal aid supporting fiscal relief and to provide City funding for programs that are warranted but should not be funded with non-recurring federal aid.

Footnotes

- This calculation appropriately removes FEMA reimbursement, which is for eligible expenses incurred prior to September 30, 2021.

- The financial plan will not include fiscal year 2026 until the Preliminary Fiscal Year 2023 Budget is released in January 2022. However, currently appropriated federal funds are to be used by December 2024; therefore, CBC assumes that City funds will be needed to continue these programs.

- The State is requiring that 50 percent of the ARP funds be spread into four equal annual installments for school years 2021-22, 2022-23, 2023-24, and 2024-25.

- U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds,” (accessed May 14, 2021), https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/coronavirus/assistance-for-state-local-and-tribal-governments/state-and-local-fiscal-recovery-funds.

- NYC is receiving $4.6 billion for the metropolitan city and $1.3 billion for the five co-terminus counties. Since there is no county government, the funds are all reflected in the City’s budget.

- Initially, FEMA was reimbursing 75 percent of eligible costs and local governments were providing the 25 percent match. The Biden Administration increased the federal reimbursement to 100 percent in January 2021. Of the $1.4 billion reflected in the Executive Budget, about $770 million is increased reimbursement for previously eligible expenses, while $600 million is for additional eligible expenses. Additionally, FEMA is authorized to reimburse governments for expenses through September 30, 2021. As a result, the City will likely receive additional reimbursements for eligible expenses incurred over the next five months.

- U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “CDC COVID-19 State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Funding” (accessed May 21, 2021), www.cdc.gov/budget/fact-sheets/covid-19/funding/index.html.

- The City is also recognizing $60 million in federal funds for special education from the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) in fiscal year 2022. City of New York, Office of Management and Budget. Fiscal Year 2022 Executive Budget: Revenue Book (April 26, 2021), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/exec21-rfpd.pdf.

- These cuts were part of the Citywide Savings Program implemented in the April 2020 financial plan. At that time, the financial plan extended through fiscal year 2024. Generally, a baseline cut that extends to the last year of the financial plan carries forward into future years. The City documentation does not clearly specify whether these cuts are included in fiscal year 2025 or not; CBC’s analysis assumes the cuts were in the baseline and would need to be restored in fiscal year 2025 and beyond.