Live From New York, It’s Excessive Tax Incentives!

Since 2004 New York State has allocated $7.8 billion in tax incentives to the film and television industry—almost enough to build two Mario M. Cuomo bridges or two Freedom Towers.1 But despite sustained and growing investment, the film tax credit has not produced enough value for New Yorkers, and should be eliminated.

Given the current state of the economy—with a 9.7 percent unemployment rate and restrictions on economic activity to curtail the spread of COVID-19—elected officials may be trepidatious about decreasing spending on an economic development program. However, several states have already eliminated or limited the ineffective credit, and the State would need to end the credit now in order for it to help stabilize the State’s finances within the four-year financial plan timeframe. With a $9 billion budget gap and projected annual deficits growing to $19 billion in fiscal year 2023, the State should continue to decrease the film tax credit until the program is eliminated. Absent outright repeal, enacting other changes would still improve the credit.

A Generous, Yet Ineffective Credit

New York provides a refundable film tax credit equal to 25 percent of qualified production and post-production costs.2 Projects filming outside of New York City, Long Island, Westchester and Rockland counties are eligible for an additional 10 percent credit for qualified labor expenses. The refundable tax credit functions as a grant—companies with credits in excess of their New York State tax liability receive a check from the State and maintain a negative tax rate.

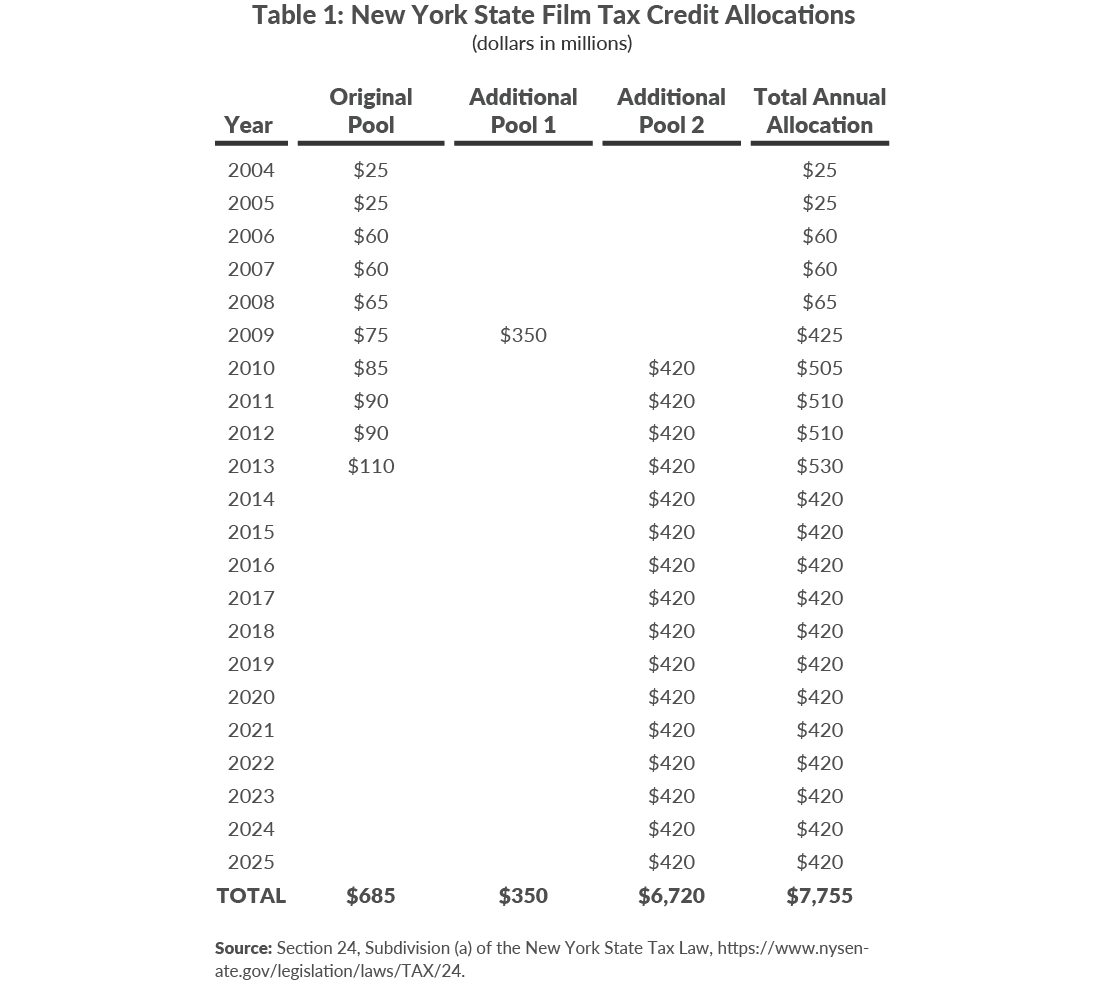

The credit was established in 2004 and capped at $25 million annually; since then it has been increased and extended multiple times, including an additional $350 million pool in 2009 because the credit was oversubscribed. (See Table 1.) It is now capped at $420 million annually through 2025; however, unlike a typical cap, once the State has awarded all credits in a given year, future year allocations are awarded for current projects. The awardee files its claim when it files taxes in the allocation year. For example, if the State has awarded all credits from the 2020 allocation at the end of June, the State will award from the 2021 allocation for a film under production in 2020. The producers will then have to wait until they file their 2021 taxes in 2022 to claim the refundable credit.

Further complicating implementation of the film tax credit, project credits in excess of $1 million must be split over two years, and project credits more than $5 million must be split over three years. Credits less than $1 million may be claimed in one year. Awarding credits from future year allocations and requiring credits to be claimed over multiple years results in multi-year delays between economic activity and state budget impact. It also means any attempt to curtail the credit will not achieve immediate fiscal relief.

While New York’s credit is expensive and complex, it is also very generous compared to other states’ credits. For example, California’s credit is 20 percent of qualified costs for most productions, total credits are capped at $330 million per year, and credits are not refundable, although they can be carried forward to offset future year’s tax liability.3 Despite California’s less generous credit, in 2019 film and television industry wages in California were more than double New York’s, and 90 percent more movies and 141 percent more television shows were produced in California than in New York.4 New Jersey offers a credit between 30 and 35 percent of qualified costs, but is capped at $100 million annually.5 According to the National Conference of State Legislatures several states are re-evaluating or paring back film incentive programs, and a number of states no longer provide a film tax credit, including Arizona, Delaware, Florida, Michigan, and Vermont.6

These efforts have been guided by research. Numerous academic studies have found that states’ film and television tax credits are not a good use of state resources. One study looked at each state’s program and found no meaningful evidence of employment gains.7 Another analysis found “movie production incentives are costly and fail to live up to their promises.”8 Part of the reason the credits are not worth the allocation of scare resources is that many of the benefits accrue to projects that would likely have been filming in New York regardless of credit. Saturday Night Live, for example, collected between $12 million and $15 million annually between 2015 and 2018, but has been filmed in New York City since its opening in 1975 and is unlikely to leave regardless of the credit.9

Empire State Development recently issued a report praising the tax credit, but its claims are based on assumptions that no filming activity would take place in New York absent the credit.10 It also over represents employment since the credit does not differentiate between full time permanent employment and temporary or part-time work.

Adopted Budget Change is a Small Step in the Right Direction

The Fiscal Year 2021 Budget extended the film tax credit one additional year to 2025 while reducing benefits by 5 percentage points. A film being shot in New York City is now eligible for a reduced credit of 25 percent of qualified costs. The budget also increased the minimum amounts required to be spent for a production to qualify for benefits, in addition to imposing other limitations.11

Absent outright repeal or phase-out, other ways the program could be improved include:

- Stop awarding from future year allocations. For a cap to be effective, it has to cap not just the annual financial plan impact, but the increase in the state liability each year.

- Stop spreading claims over 3 years. In combination with awarding from future year allocations, it means the distance between job creation and State financial impact is extended. This means that if the State ends the subsidy, there will still be more claims to pay.

- Decrease the credit substantially to 10 percent of qualified costs and eliminate the annual cap. This will substantially decrease the cost of the program, which would make the annual cap unnecessary and ensure that there is no need to draw down claims from future allocations.

- Further decrease the share of expenses that can be claimed in New York City. The State’s recent decrease of qualifying expenses produced little opposition. By phasing out the credit in New York City and keeping it outside of New York City, it will push some production to areas of the state that have a much greater need for economic development.

New York’s film tax credit is a very expensive incentive to provide at a time when New York State is withholding payments to school districts, nonprofits, and others. Through the credit, the State has allocated more than $7 billion to the film and television industry, with the overwhelming majority of credits for projects in New York City.12 It time for the State to say, “That’s a wrap!” on the film tax credit.

Footnotes

- Katie Warren, “NYC's new One World Trade Center dominates the skyline — but I went inside and it didn't look like the bland, traditional office building I was expecting”(Business Insider, Dec 12, 2018), www.businessinsider.com/inside-nyc-new-world-trade-center-freedom-tower-photos-2018-10.

- Qualified costs are eligible for a credit equal to 30 percent of costs for any application filed before April 1, 2020. “Qualified [production] costs generally include most below-the-line items associated with production such as set construction, crew, camera equipment, grip equipment, props, etc. Post-production costs such as film editing, sound design and effects, and visual effects may be qualified costs for purposes of the film production credit.” See: Empire State Development, “New York State Film Tax Credit Program” (accessed March 10, 2020), https://esd.ny.gov/new-york-state-film-tax-credit-program-production.

- California Film Commission, “Film & TV Tax Credit Program 3.0” (accessed March 9, 2020), http://film.ca.gov/tax-credit/program-3-0/.

- Motion Picture Association, “What We Do: Driving Economic Growth, Film and Television Economic Contribution by State” (accessed October 19, 2020), https://www.motionpictures.org/what-we-do/driving-economic-growth/#map.

- NJ Motion Picture & Television Commission, “Financial Incentives” (accessed March 9, 2020), www.nj.gov/state/njfilm/incentives.shtml.

- National Conference of State Legislatures, State Film Production Incentives & Programs (January 30, 2018), p. 1, www.ncsl.org/Portals/1/Documents/fiscal/2018StateFilmIncentivePrograms_20189.pdf.

- Michael Thom, “Do State Corporate Tax Incentives Create Jobs? Quasi-experimental Evidence from the Entertainment Industry” (State and Local Government, v 51 no 2 June 2019), https://journals.sagepub.com/eprint/UVNGRDZI6JADTRHH3NWY/full.

- William Luther, “Movie Production Incentives: Blockbuster Support for Lackluster Policy” (Tax Foundation Special Report, January 2010), https://files.taxfoundation.org/legacy/docs/sr173.pdf.

- Michelle Breidenbach, “NY Taxpayers Have Given $1.2 billion to these 43 TV Shows, Movies in Last Four Years” (Albany Business Review, February 22, 2019), https://www.bizjournals.com/albany/news/2019/02/22/new-york-tax-credits-film-industry-movies-tv.html.

- EFPR Group, CPAs, PLLC, Independent Review of the Empire State Film Production and Post Production Credit; New York State Urban Development Corporation (April 2019), https://esd.ny.gov/sites/default/files/Financial-Operational-Review-ESD-Film-Credit-2017-18.pdf.

- The budget also stopped new sketch shows from qualifying for the credit. It also imposes $1 million minimum budget for projects in New York City, Nassau, Suffolk, Westchester, or Rockland. Minimum of $250K elsewhere.

- Michael N’dolo, Rachel Selsky, and Amie Collins, Economic Impact of the Film Industry in New York State 2017 & 2018 (Camion Associates, April 2019), pp. 11-13, https://esd.ny.gov/sites/default/files/Camoin_NYS-FilmReport-2017-18.pdf.