Narrowing New York's Health Insurance Coverage Gap

Download the press release here.

A copy of this report can also be found on the Community Service Society's website here.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Health insurance improves health, increases life expectancy, and bolsters economic security by reducing medical debt and bankruptcy. New York State has historically provided more coverage options than most other states, including broad eligibility for Medicaid and other public programs even before it fully implemented the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The ACA’s benefit improvements, financial premium subsidies, and Basic Health Program option helped reduce New York’s uninsured rate from 11.9 percent in 2010 to 5.2 percent in 2019.

Still, more than 1 million New Yorkers remained uninsured and New York ranks seventh among states on coverage. Narrowing this coverage gap is challenging and states have developed innovative strategies to meet the challenge, including state individual mandates, state premium assistance programs, coverage expansions, using tax returns to boost enrollment, and creating state-sponsored public options. New York could meaningfully reduce the number of uninsured people by adopting one or more of these strategies.

This paper provides a guide for New York policymakers to five strategies for increasing coverage rates.1 Each section describes design and implementation issues related to New York’s health care environment and estimates the increase in enrollment and cost to the State. These estimates are based on State administrative data, federal data such as the U.S. Census, and evaluations of efforts implemented in other states.

The coverage gap is one barrier among many that reduces access to care, imposes extraordinary financial burdens on patients, lowers quality of care, and creates and perpetuates inequities. Other health system changes also are needed to address these problems, ensure the system is fiscally sustainable and improve access to high quality care. However, narrowing the coverage gap is vitally important and would greatly benefit the health and finances of newly insured New Yorkers. This report is intended to encourage robust debate about how to achieve that goal.

The 1 Million Uninsured New Yorkers

Individuals remain uninsured for one of four reasons: (1) they are unaware of or do not understand their coverage options and the enrollment processes; (2) they choose not to enroll for political or religious reasons; (3) they have a high risk tolerance and self-perceived good health status; or (4) they consider the coverage available to them to be unaffordable.

Prior to the pandemic and the recession it caused, roughly 1 million New Yorkers lacked insurance. Assuming that 2023 insurance rates and distribution will mirror 2019, roughly 345,000 of these will be eligible for but not enrolled in public coverage options like Medicaid, the Essential Plan or Child Health Plua (CHP); another 421,000 will have access to employer or self-purchased coverage but have not enrolled due to cost, low perceived value, or other reasons; and 245,000 uninsured individuals will have an immigration status that renders them ineligible to participate in public programs like Medicaid, the Essential Plan, and Qualified Health Plans offered through the State’s Marketplace.

Five Strategies to Narrow the Coverage Gap

This report analyzes five strategies for reducing the number of uninsured in these three groups.

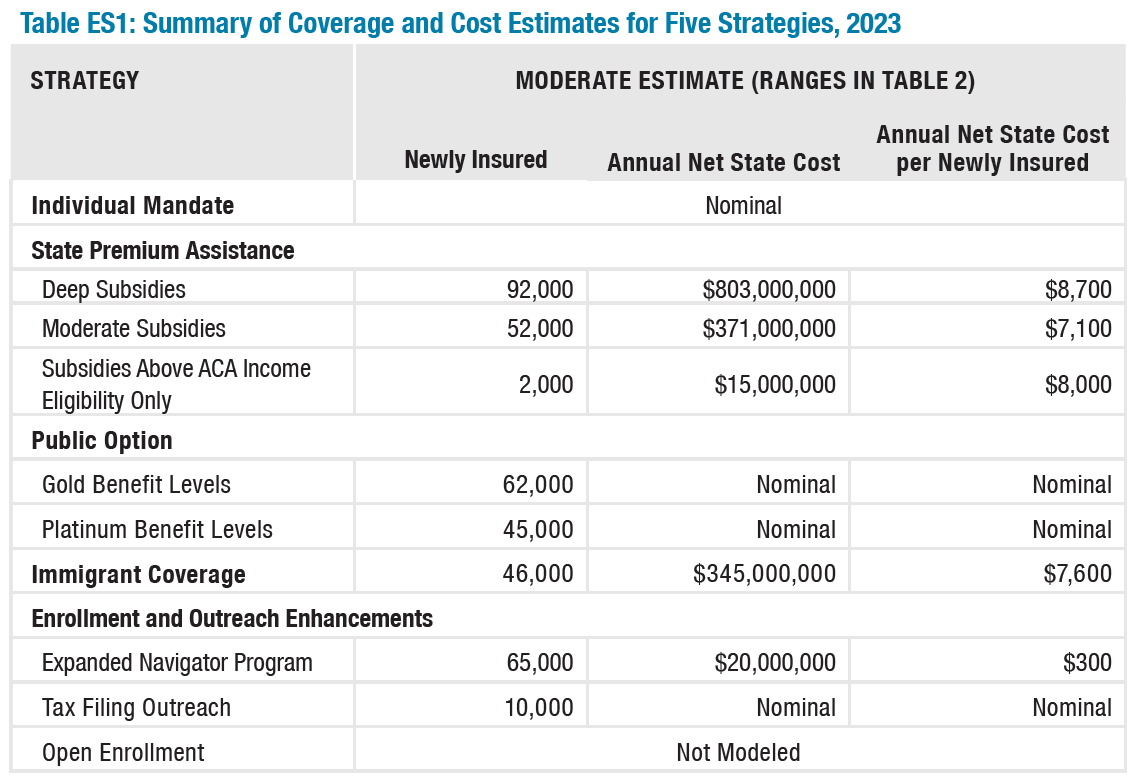

One strategy, a state individual mandate, would have only a nominal effect. The others – enhanced outreach and enrollment, a public option, expanded eligibility for immigrants, and premium subsidies – would increase the number of people with insurance by between 10,000 and 92,000 if implemented alone. The largest effect was from premium subsidies at the highest amount modelled with an estimated annual State cost of up to $803 million ($8,500 per new enrollee). (See Table ES 1.) Some of these strategies can be mutually reinforcing, such as a mandate and premium subsidies, but for this paper each is estimated separately. Importantly, ranges of cost and coverage impacts have been estimated to appropriately reflect the specificity of the evidence and assumptions used. Generally, moderate estimates are presented to best convey the estimated magnitude of the impacts.

Strategy #1: State Individual Mandate and Penalty

New York could replace the federal mandate penalty that was repealed in 2018 with an identical policy at the State level. There is little evidence, however, that the federal mandate elimination had a negative effect on insurance rates in New York, so imposing a State mandate is unlikely to significantly increase the number of people insured. Still, the administrative cost would be nominal and the State could consider implementing a mandate to protect against individuals relinquishing insurance in the future and causing instability in the individual market.

Strategy #2: State Premium Assistance Program

People who earn between 200 percent and 400 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) receive federal subsidies to buy individual market plans. The subsidies are calculated to cap the percent of their income they would need to use to purchase a Silver-level plan. However, many New Yorkers who would get these subsidies are not enrolled. New York could provide additional subsidies to reduce the cost of individual market plans for more people. Three premium subsidy designs were analyzed:

- Deep subsidies for people earning between 200 percent and 600 percent of the FPL that limit premium costs to between 1 percent and 6 percent of household income;

- Moderate subsidies for the same income levels that limit premium costs to between 3 percent and 8.5 percent of household income (which match the temporary enhanced subsidies created by the American Rescue Plan); and

- Subsidies only for those earning between 400 percent and 600 percent of the FPL that limit premium costs to 10 percent of household income.

The biggest effect is for the deepest subsidy, with a moderate estimate of 92,000 newly insured for an annual cost of $803 million. The moderate subsidies would produce about 52,000 newly insured for a cost of $371 million. The subsidies for people earning between 400 percent and 600 percent of FPL only would produce about 2,000 newly insured for an annual cost of $15 million. Other effects were not modelled including increased revenue for health care providers and stable or lower premium costs as a result of increasing the size of the individual market.

Strategy #3: State Public Option Plan

New York could procure and offer a plan through the State Marketplace with lower premiums and less cost-sharing than plans currently available. It could do this by imposing stricter limits on administrative costs and profits for insurers and paying lower provider reimbursement rates than currently paid by New York’s commercial insurers. Effects were analyzed for a Gold-level and a Platinum-level plan. Bronze-level plans were excluded after preliminary analysis suggested this would not have an impact on coverage rates, and Silver-level plans were excluded to avoid disrupting federal premium subsidy calculations.

The moderate estimates of the number of newly insured individuals are 62,000 for a Gold plan and 45,000 for a Platinum plan. This strategy would have little or no direct cost to New York State beyond marginal administrative costs. Federal costs would increase by between $110 million and $287 million for subsidies for the newly insured. There also could be significant impacts on providers (particularly safety-net providers with a lower portion of commercially insured patients), who would receive lower reimbursement rates for some of their patients, and on insurers, whose resources to pay for non-medical costs would be reduced for some of their members; these effects should be considered and are not modeled here.

Strategy #4: State Program for Low-income Immigrants

A large portion of uninsured New Yorkers are prohibited from federally-funded coverage options because they are undocumented or are lawfully present but remain ineligible for coverage due to their status. New York provides coverage to some members of this population through State-only funding for Medicaid and Child Health Plus, and could use a similar strategy to create a State-only funded Essential Plan. The Essential Plan is the brand name for New York’s Basic Health Plan and is fully funded by the federal government.

A State-funded Essential Plan that uses the same income eligibility (up to 200 percent of the FPL) would provide insurance for an estimated 46,000 new enrollees for an annual net State cost of $345 million, accounting for savings from spending offsets for emergency Medicaid. Other effects were not modelled including increased revenue for health care providers.

Strategy #5: Enhanced Outreach and Enrollment Strategies

Enhancing outreach to the uninsured and providing more enrollment assistance would help insure more of the New Yorkers who are already eligible for low-cost coverage. Three strategies analyzed are:

- Expanding the Navigator program to enroll people in areas where more are uninsured than the state average. The remaining uninsured population is not evenly distributed across the state. New York could provide additional funding for the State Navigator program to target areas where fewer people are insured than average. If New York increased insurance rates in those areas to the average (about 5 percent uninsured), an estimated 65,000 uninsured people would obtain coverage. Incremental costs for enrolling more people through the existing program would be up to $300 per enrollee or about $20 million in total.

- Enable enrollment through tax returns similar to the Maryland Easy Enrollment Health Insurance Program. Maryland’s tax returns ask individuals if they would like to check their eligibility for health insurance programs. People who qualify for Medicaid or CHP are sent plan options and are automatically enrolled if they do not respond. Those eligible for Marketplace coverage are given a special enrollment period. If New York had the same program outcomes as Maryland, an estimated 10,000 additional people would obtain health insurance.

- Expand enrollment opportunities outside of open enrollment. Uninsured New Yorkers who seek to purchase insurance outside of open enrollment can only do so under some circumstances including pregnancy, job loss, and moves. Massachusetts provides a special enrollment period for people who are buying Marketplace plans for the first time and earn up to 300 percent of the FPL. It also allows those who missed open enrollment to testify that their failure to enroll was unintentional and for those who lose coverage but miss the 60-day deadline to re-enroll to testify that they were unaware of the deadline. New York could adopt similar policies. The number of new enrollees and the possible market destabilization that could occur are not estimated. although there is no evidence of adverse selection or market destabilization from existing special enrollment periods in New York or in Massachusetts.

These strategies would increase the State’s costs for the health insurance programs that enrolled more already eligible people. Those costs are not modelled. Like the other strategies, they would increase revenue for health care providers by reducing uncompensated care.

Conclusion

Increasing the number of insured New Yorkers will improve their health outcomes and economic security. The strategies and findings described in this paper are meant to stimulate and ground the debate on how to increase

the number of New Yorkers that have health insurance.

Specific designs presented here are not exhaustive and permutations of each strategy exist and may be worthy of consideration. Some important effects of these initiatives, including those on the insurance marketplace, insurers, providers, and the cost of covering those already eligible, are not modelled here. These would have significant effects on New York’s patients, the health care system, and the State budget and should be seriously considered by policymakers when choosing strategies to narrow the coverage gap. Still, this paper’s findings, and strategies and designs should be productive starting points for discussion of the problem generally and each option specifically.

Download the Full Report

Narrowing New York's Health Insurance Coverage GapFootnotes

- This paper does not does not address a single-payer or universal coverage system for New York State, which was modelled in Jodi L. Liu and others, “An Assessment of the New York Health Act: A Single-Payer Option for New York State,” (Rand Corporation, 2018), https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2424.html.