Opportunity Zones In New York State and City

Created as part of the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA), the Opportunity Zone (OZ) program is a place-based economic development tax incentive intended to increase private investment in low-income communities. The program, however, may come at a high price to taxpayers. Congress’ Joint Committee on Taxation estimates the OZ program will cost $2 billion in lost federal revenue annually. State and local governments that provide incentives conforming to the federal program will face additional losses. In New York those losses may amount to as much as $63 million annually for New York State and an additional $31 million annually for New York City before rising substantially in 2029. Despite these potential revenue losses, TCJA did not require the Treasury Department to track investments in OZ funds or investments made by funds in specific projects.

New York has decided to conform to the federal program; capital gains deferred or excluded from taxation at the federal level will be similarly deferred or excluded from state and local taxes. Given this decision, State lawmakers can take steps to ensure that the OZ program is well targeted and that the public can evaluate its implementation and impact.

This report summarizes the OZ program, explains how New York State chose the areas that are eligible for the program, estimates the program’s cost to state and city taxpayers, and identifies options for how New York can make it more transparent and better targeted.

How the Opportunity Zone Program Works

The OZ program is designed to encourage individuals and corporations to invest in real estate projects and businesses in low-income communities. Under the program, individual and corporate taxpayers can defer the taxes due on realized capital gains by investing in Qualified Opportunity Funds, which are required to invest in projects, businesses, and real estate in census tracts designated by states as Opportunity Zones.1 Depending on the duration of their investment, taxpayers are able to defer and potentially reduce taxes on their original gains. As an additional incentive, appreciation on the gains invested in an Opportunity Fund are exempt from federal capital gains taxes. Maximum benefits are available to investors who invest in Opportunity Funds by the end of 2019 and hold their investments for a minimum of 10 years.2 (See the text box for a description of how the tax benefits work for a typical investor.)

For investors and fund managers, the combination of deferring gains, reducing tax bills, and excluding future gains from taxation will boost returns on investment. For cities and states, the program presents an opportunity to attract additional private investment to low-income or high poverty neighborhoods. For developers and business owners, the program promises to increase the availability of equity capital.

How Opportunity Zone Tax Benefits Work

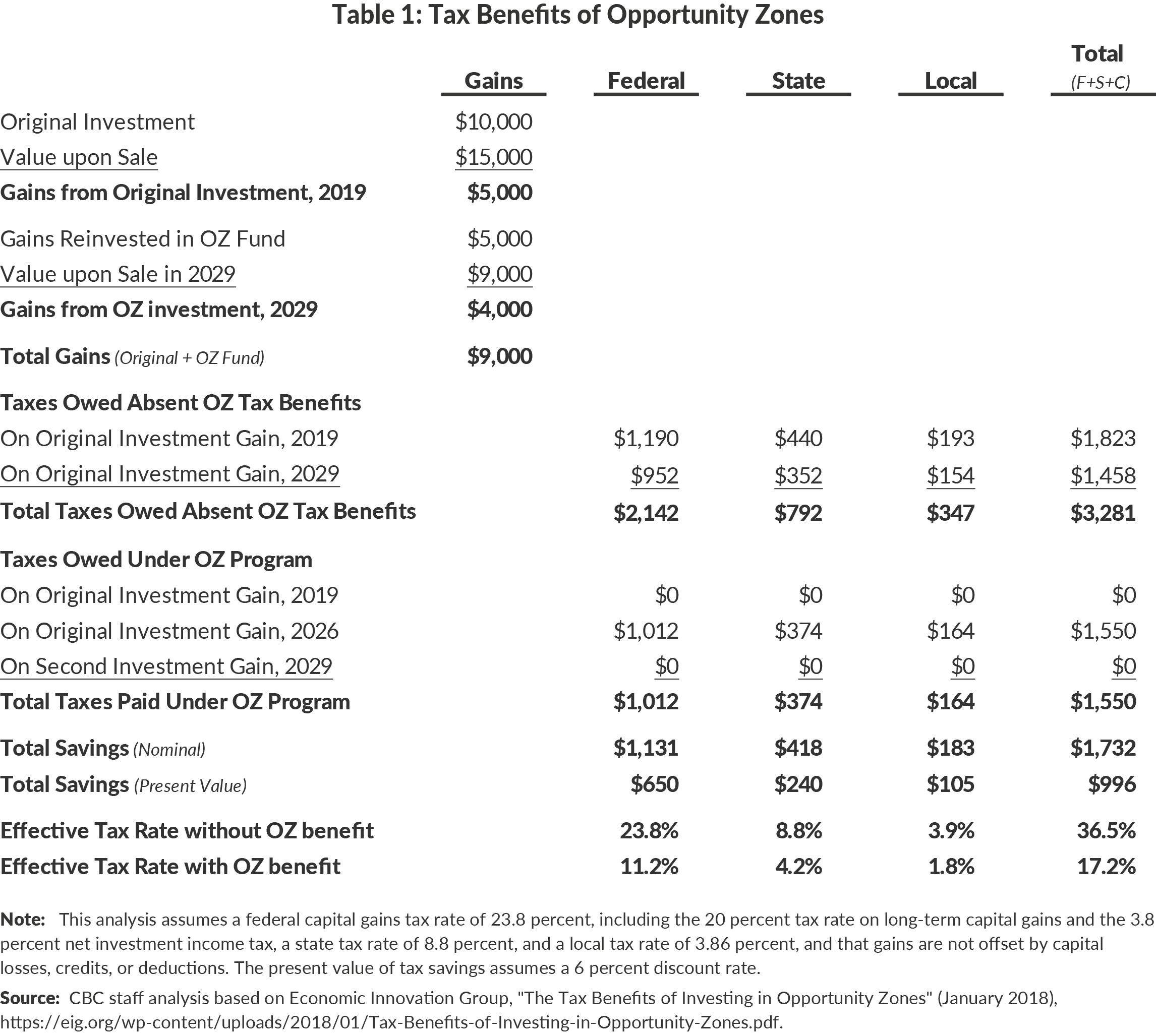

The Opportunity Zone program allows both individuals and corporations with capital gains to reinvest the gains into Qualified Opportunity Funds. In the hypothetical example below, an individual New York City resident sells an asset in 2019 and realizes a capital gain of $5,000. That same year, she invests her $5,000 gain in a Qualified Opportunity Fund and holds it until 2029, at which point she liquidates the investment for $9,000, realizing an additional $4,000 in capital gains. This allows her to realize the maximum benefits allowed under federal law, which include the deferral of taxation on the original gain until 2026, a 15 percent increase in the basis of the original investment (which reduces the gains subject to taxation), and a full exclusion from taxation on any appreciation on investments in the Qualified Opportunity Fund because it has been held for a minimum of 10 years.

With the OZ benefits, she can defer taxes on her original gain until 2026, at which point she would owe $1,550. The gains on the second investment are excluded from taxation. The combined federal, state, and local effective tax rate with OZ benefits is 17.2 percent. (See Table 1.)

Without the OZ program, she would have owed $1,823 in federal, state, and local taxes on the sale of her original investment in 2019. If she were to make a second investment of $5,000 in 2019 that achieved the same rate of return as the OZ project, she would owe $1,458 in taxes on the sale of her subsequent investment in 2029 for a combined tax payment of $3,281—an effective tax rate of 36.5 percent.

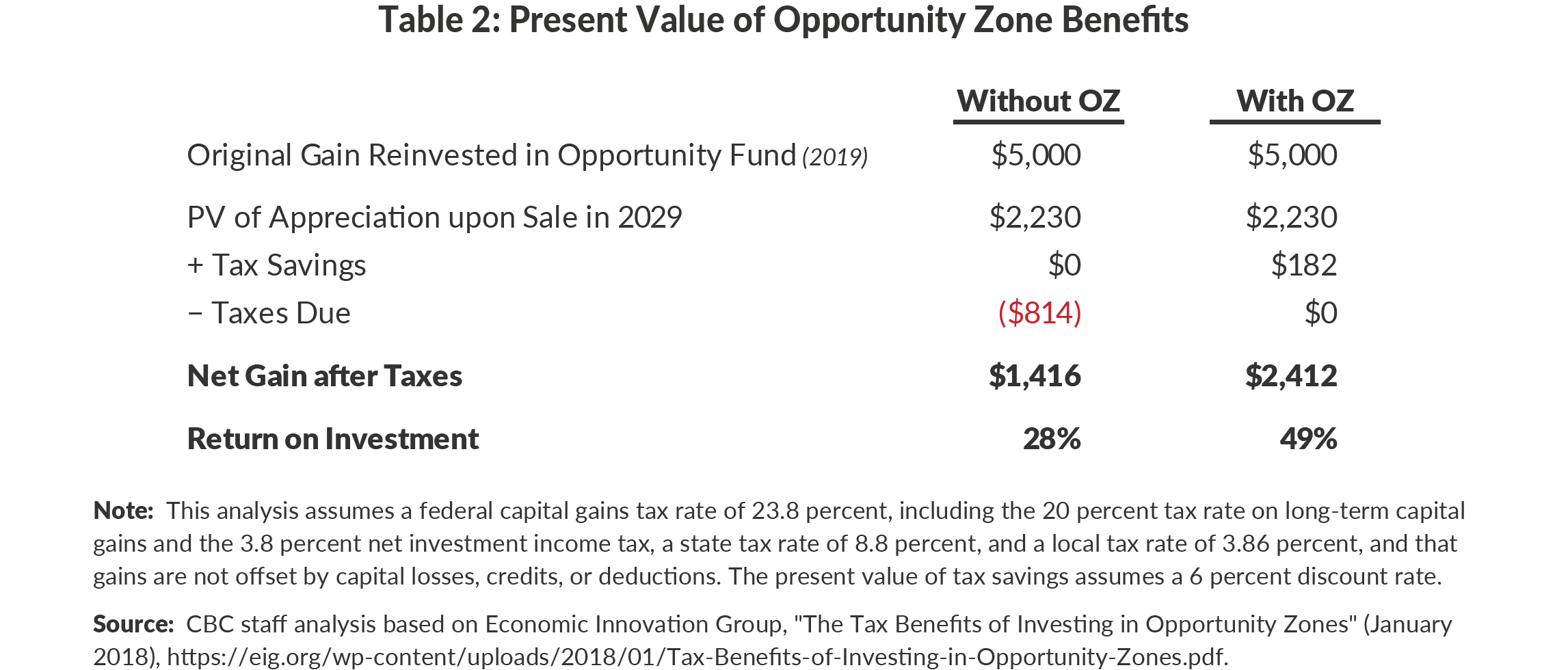

On a present value basis, using a discount rate of 6 percent, the tax benefits offered by the OZ program would save her $996. The vast majority of the savings (82 percent, or $814) is generated by the exclusion of future gains from taxation.

These tax benefits also allow her to boost the rate of return on the subsequent investment. Table 2 shows that the combined impact of the deferral, step-up in basis, and exclusion of future gains from taxation increases the return on her investment over the ten-year period from 24 percent to 49 percent. (For the non-OZ investment, this analysis does not take into account the need to invest additional capital to make up for taxes paid on the original gain in 2019. For the OZ investment, it assumes that she uses outside funds to pay the deferred tax bill in 2026 rather than liquidating a portion of her OZ investment.)

How New York’s Opportunity Zones Were Selected

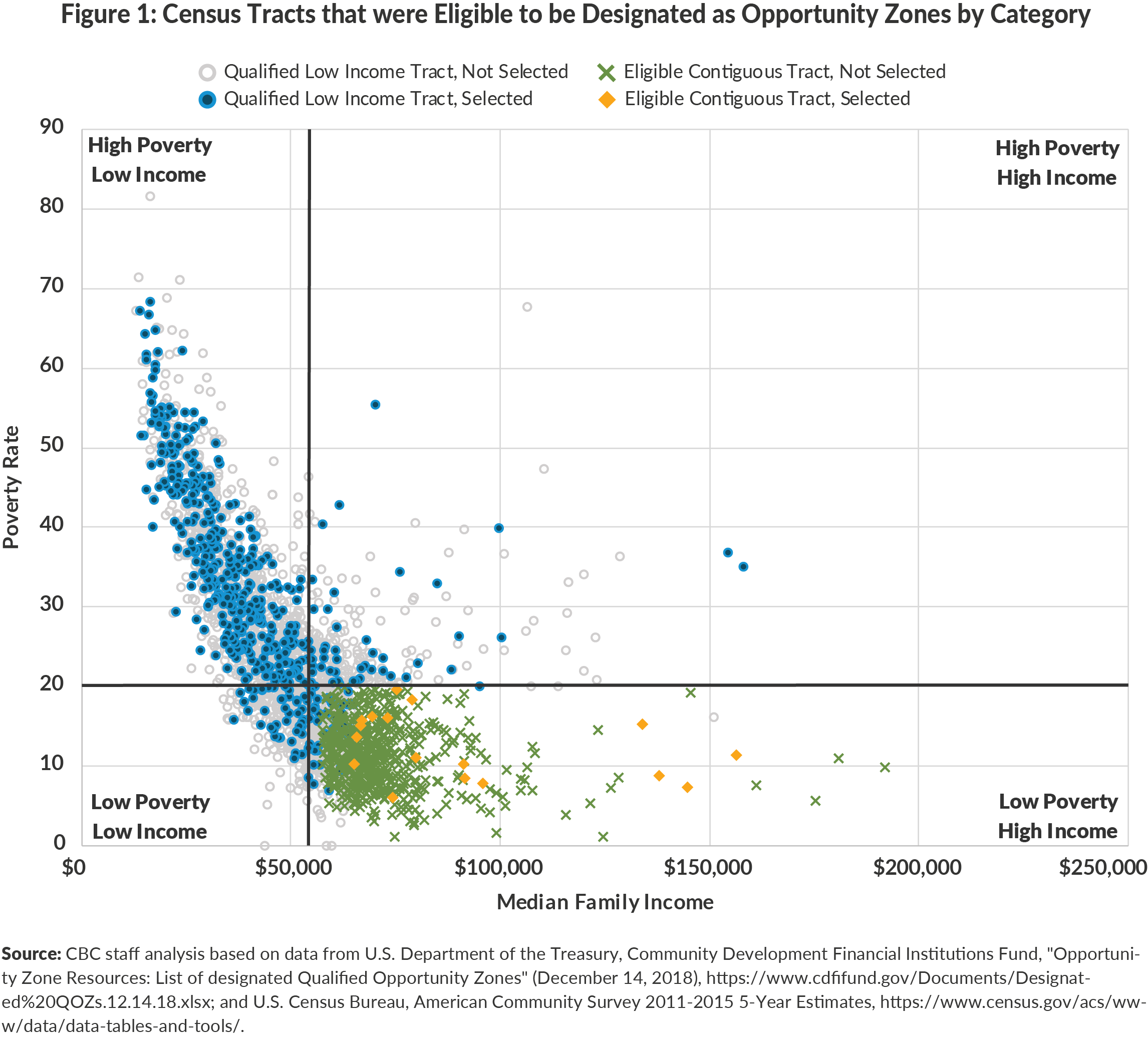

TCJA allowed governors to designate up to 25 percent of census tracts that meet specific demographic criteria in their states as OZs. To be eligible a census tract must have a poverty rate greater than or equal to 20 percent, or have a median family income less than 80 percent of the greater of its statewide median or the median for its metropolitan area.3 These measures were based on data from the 2011-2015 American Community Survey (ACS) Five-Year Estimates. Governors could also designate up to 5 percent of their states’ OZs from a list of tracts that were ineligible based on criteria but that were contiguous with eligible low-income tracts and had a median family income that was no more than 125 percent of the adjacent eligible tract. In the 2015 ACS, the statewide poverty rate in New York was 15.7 percent, and 80 percent of the statewide median income was $57,530.

In New York, Governor Andrew Cuomo tasked Empire State Development Corporation (ESD), the state’s economic development entity, and New York State Homes and Community Renewal, its housing agency, with designating OZs. After informal consultations with the Regional Economic Development Councils (REDCs) and local officials, ESD and the Governor selected 514 tracts. Of these 496 were qualified low-income tracts and 17 were non-low-income contiguous tracts. Unlike some states, the selection of zones in New York was not subject to public discussion or review.4

As shown in Table 3, the tracts selected fall into four categories:

- High-Poverty/Low-Income: Nearly three-quarters of the census tracts selected met both the income and poverty criteria. These high-poverty/low-income tracts were also the most likely to be selected; 30 percent of all eligible high-poverty/low-income tracts were designated as OZs. These tracts include some of the poorest and most disadvantaged communities in the state, including much of the Bronx, Central Brooklyn, and many Upstate cities.

- Low-Poverty/Low-Income: Seventeen percent of selected tracts meet the income threshold but not the poverty threshold. These tracts are not as disadvantaged as the high poverty tracts, but still are home to a significant number of low-income households.

- High-Poverty/High-Income: Six percent of selected tracts meet the poverty threshold despite having median family incomes at or above than their regional median. A number of the tracts that fall into this category have family incomes that are well above the statewide median; several outliers have median family incomes in excess of $100,000.5

- Low-Poverty/High-Income: ESD also selected 17 tracts that met the standard for contiguous, non-low-income eligible tracts. This is fewer than the number that could have been selected under federal law, which allowed New York to designate up to 26 non-eligible contiguous tracts. The contiguous tracts selected by ESD have median family incomes similar to the high-poverty/high-income tracts. Most (14 of the 17) are located in New York City. The three outside New York City are in Calverton (Suffolk County) at the site of the former Grumman air field, Cobleskill (Schoharie County), and a portion of Tioga County home to Tioga Downs casino and race track. A majority of the contiguous tracts in New York City are also adjacent to tracts in the high-poverty/high-income quadrant, which suggests that some of the outlier high-poverty/high-income tracts may have been picked in part to select contiguous tracts that otherwise would have been ineligible. (All but one of these outlier parings are located in New York City.) Figure 3 highlights the contiguous tracts in New York City along with bordering high-poverty/high-income tracts designated as OZs.

Revenue Impacts in New York

The OZ program could be costly to taxpayers. Analysts estimate that taxpayers have up to $6 trillion in unrealized capital gains nationally.6 Unlike other federal community development programs (such as New Markets Tax Credit), TCJA did not cap the amount of gains taxpayers could invest in Opportunity Funds or the amount that funds could invest in projects. As of August 2019 organizations tracking the public statements of fund managers report that funds intend to raise up to $53 billion to invest in OZ projects.7

The Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates the OZ program will cost the federal government $2 billion annually, with $1.5 billion claimed by corporations and $500 million claimed by individuals, for a total cost of $9.4 billion for federal tax years 2018 to 2022.8 This would make it the costliest federal community development tax expenditure program, and one-third more expensive than the annual cost of the New Markets Tax Credit program, another federal program that allocates tax credits to encourage investment in businesses and real estate projects in low-income communities.

At the federal level, long-term capital gains are taxed at lower rates than ordinary income. Following the passage of TCJA, the top marginal income tax rate is now 37 percent, while the top tax rate on capital gains is 20 percent, plus an additional 3.8 percent net investment income tax. C corporations are also subject to capital gains taxes, but do not receive preferential tax treatment. Gains realized by corporations are taxed at the regular corporate tax rate of 21 percent.9

New York State has elected to conform to the federal tax treatment of capital gains invested in qualified opportunity funds. Any gains deferred or excluded from taxation at the federal level also will be deferred or excluded from the calculation of tax liability at the state and local levels in New York.

New York residents stand to benefit more from the OZ program than residents of other states. Unlike the federal government, New York does not tax capital gains at a preferential rate. Taxpayers are taxed on gains at the same rate as earned income – an 8.8 percent top marginal rate at the state level and an additional 3.876 percent top rate for New York City residents. For individual taxpayers living in New York City, the top marginal tax rate on gains, combining federal, state, and local taxes, is 36.48 percent. New York City also taxes gains earned by some pass-through entities through the Unincorporated Business Tax. Income earned by S-corps is subject to the General Corporation Tax. (Data on the gains claimed by corporations are not available.)

New York State also accounts for a disproportionate share of the nation’s capital gains income. In tax year 2014, New York had 6 percent of the U.S. population but its $93.5 billion in realized capital gains accounted for 14 percent of all capital gains claimed by individual taxpayers. New York City had less than 3 percent of the national population, but individual taxpayers realized $49.2 billion in gains, more than 7 percent of all gains nationwide. (See Table 4.)

New York State businesses also represented about 8 percent of business income taxes collected at the federal level. In state fiscal year 2018, corporations, banks and insurance companies paid $4.2 billion in taxes, while in New York City, the general corporation and unincorporated business income taxes generated nearly $6.4 billion in revenue. The portion of both state and local corporate tax revenue generated from capital gains is not publicly available.

Estimating the State and Local Revenue Impact of Opportunity Zones

The New York State Department of Taxation and Finance’s preliminary report on the impact of TCJA estimated the cost of conforming to the OZ provision to New York State as $7 million per year.10 (It did not estimate local costs.) This estimate, which was produced in January 2018 based on a preliminary federal fiscal impact figure, may be too low.

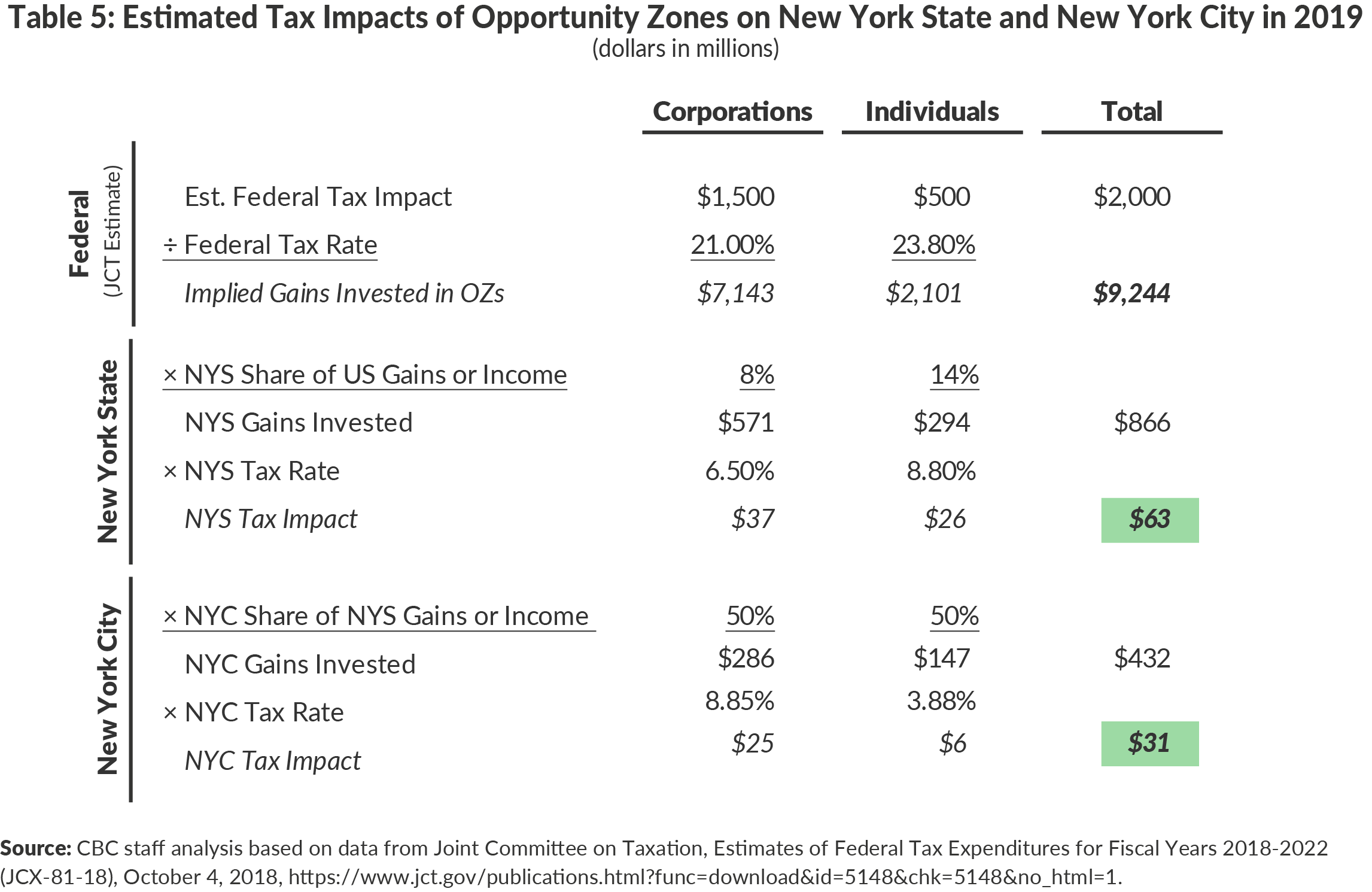

JCT’s estimated $2 billion federal fiscal impact implies taxpayers will defer taxation on $9.2 billion in capital gains each year based on current federal tax rates for corporations and individuals. Assuming New York State’s historic shares of U.S. corporate business income receipts and individual capital gains and New York City’s share of statewide income remain at their current levels, CBC estimates New York State taxpayers will invest approximately $866 million annually in Qualified Opportunity Funds, with half coming from New York City. At current tax rates the 2019 fiscal impact of that level of investment could be as much as $63 million on New York State and $31 million on New York City. (See Table 5.) The actual fiscal impact will depend on the amount of gains that taxpayers realize, the share of gains reinvested in OZs, the timing of initial investments and liquidations, and taxpayers’ effective tax rates.

Some of this forgone tax revenue may be deferred to 2026, at which point governments may see a one-time boost in tax receipts. The JCT’s initial cost estimate of the OZ program for federal tax years 2018 to 2027 assumed $12.4 billion in lost revenue through 2025, which would be offset by a $10.8 billion increase in revenue in 2026 and 2027 as taxpayers make deferred tax payments. If New York State conforms, it would likely see a similar increase in those years, which would offset a portion of the revenue foregone in previous years.

These costs, however, represent a small share of the tax benefits enjoyed by investors and the costs borne by federal, state, and local governments. The fiscal impact of excluding future gains from taxation, which represent 80 percent of the tax benefits offered by the OZ program, will not occur until 2029 at the earliest.

In the example shown in Table 2, every dollar of tax benefits from the initial deferral of taxes in 2019 would generate an additional $4.50 in tax benefits from the exclusion of future gains from taxation. If this occurs, the fiscal impacts on New York State and New York City could increase dramatically to $284 million and $140 million in 2029, respectively. These losses will occur only as Opportunity Funds sell assets and investors realize gains that would otherwise be subject to taxation.

Some of these losses may be offset by increases in other revenue sources, such as sales taxes on construction materials or taxes on increased corporate profits, if the OZ program incentivizes investment that would not have happened otherwise. On the contrary, if the OZ investments flow to projects that would have happened anyway, the exclusion of future gains from taxation means that New York will forgo future revenue that it likely would have been able to collect.

Three Concerns about the OZ Program

Three issues merit consideration by State lawmakers, as the New York taxpayers continue to invest in OZ funds and as funds begin to deploy capital.

1. OZs Could Subsidize Investments that Would Have Occurred Anyway

It is unclear how many projects that will benefit from OZ investments would have happened in the absence of an incentive. The OZ program’s benefits–preferential tax treatment for gains on equity investments–may not induce projects that would not otherwise have been feasible. While stakeholders have expressed hope that the program will increase investment in marginal projects, some investors have said the program would not incentivize them to make investments they would not make without the tax benefits.11 Equity investors who receive the tax benefits will still demand a return on their investments, whether through a share of annual operating income or proceeds upon sale, independent of the incentive.

In many cases, OZ tax benefits would be in addition to other incentive programs that are available in OZs. This “layering” of incentives is a common and problematic feature of New York State and local economic development policies.12 The NMTC and Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) programs allow developers to sell federal tax credits to investors in exchange for equity investments that effectively act like capital grants. Private activity bonds and publicly subsidized loans allow companies or developers access to low-interest debt financing. In New York developers active in OZs can receive tax breaks from local Industrial Development Agencies, tax credits through the Excelsior program, and grants from REDCs. In New York City, commercial projects can also benefit from the Industrial and Commercial Abatement Program and the Relocation and Employment Assistance Program, and most large residential development receive property tax abatements or exemptions through the 421-a housing program.

To date the State has not analyzed how the OZ program will interact with other State and local incentive programs or whether it would induce projects that otherwise would not have been feasible.

2. Lack of Oversight and Accountability

Currently there is no commitment from federal officials to track, monitor, or evaluate the Opportunity Zone program. Without additional legislation or rulemaking, the public will not be able to monitor how much taxpayers are investing in funds, where funds are investing their assets, or whether the OZ program is meeting its stated goals. The NMTC program, for which projects are vetted according to their projected community benefits, had a similar voluntary reporting and evaluation framework when it was first created. The voluntary approach yielded little information and was ultimately replaced with a mandatory compliance and reporting framework.13

Following the passage of TCJA, legislators have introduced bipartisan legislation in the U.S. Senate that would require funds to report on their investment activities and their impacts on job creation and housing production. The U.S. Treasury has also issued a request for information on how it can best measure the effectiveness of the program.14 These efforts may yield robust reporting and transparency measures, but their passage and implementation remain uncertain.

3. Zone Designations Remain Fixed Over Time

The initial OZ designations will remain in place through at least 2026. This is problematic for two reasons. First, eligibility was based on data from the 2011-2015 American Community Survey, which was already outdated at the time of selection. Second, the OZ boundaries will not adjust to account for neighborhood change and development over time.

The demographics of most high-poverty/low-income tracts will likely remain constant, but a number of tracts designated as OZs in New York have undergone substantial demographic changes over the last decade.

Using data from the 2013-2017 ACS 5-Year Estimates instead of the 2011-2015 Estimates, just 69 percent of high-poverty/high-income tracts and 82 percent of low-income/low-poverty tracts that were selected still meet OZ eligibility guidelines. By contrast, 99 percent of high-poverty/low-income tracts still qualify. These figures are even starker within New York City: just 57 percent of high-poverty/high-income tracts still qualify. These neighborhoods will remain eligible for new OZ investment even though their demographics no longer meet the criteria for the program.

Options for Improving the Implementation of Opportunity Zones in New York State

New York State lawmakers can improve the New York’s Opportunity Zone implementation through two potential approaches: taking steps to increase transparency; and exploring decoupling in part or in full.

1. Increase Transparency

The State can require Opportunity Funds operating in New York State to report on their activity in order to qualify for state tax benefits. CBC’s blueprint for economic development reform includes a framework for how these reports can be structured. The Opportunity Zone Reporting Framework developed by U.S. Impact Investing Alliance, the Beeck Center at Georgetown University, and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York offers an additional approach that can be adopted.15 At a minimum, these reports would include information on the location of projects, the amount invested, the intended use of the funds, estimates of the number of jobs or housing units built, and the actual number of jobs created or housing units built.

In addition, the State could require funds to report annually on the value of gains invested by New York State taxpayers in qualified opportunity funds. Requiring funds to report on the investments made by New York taxpayers who would otherwise be subject to New York state and local taxation is necessary to understand the fiscal impacts of the OZ program on personal income and business income revenue.

Data on where OZ funds are investing and how much New York taxpayers are investing would allow the State to publish annual reports on the OZ program and include the information in a database of economic development deals.16 This would facilitate an appropriate periodic evaluation of OZ performance and impact, including reporting on the “layering” of incentives granted to specific projects or businesses. It would also mirror the reporting requirements of other place-based state and city incentive programs. State law, for example, requires recipients of the Excelsior job creation program and START-UP NY to submit annual performance reports showing the number of jobs created and investments made.

2. Decouple from the Federal OZ Program

There are several steps the legislature can take to decouple partially or fully from the federal OZ program.

One option to decouple in part would be to limit the types of OZ projects that would qualify for state tax benefits. For example, the legislature could pass a bill that would limit benefits to residential projects that meet a minimum affordability threshold for a fixed set of time or to commercial projects that are consistent with an REDC strategic plan. Adding this certification step would ensure that OZ projects deliver public benefits in order to get tax benefits. It could also allow state and local governments to reduce the value of subsidies that they would provide through other programs.

Another option would be to limit the number of OZs in which taxpayers could claim state benefits. The State could limit benefits to zones that meet both the poverty and family income thresholds, or to those that meet the criteria based on the most recently available Census data. This would ensure that state tax benefits are limited to the communities most in need of investment and would address concerns about the changing demographics of zones that were selected based on outdated census data.

A third option is to decouple fully from the federal program. There is no requirement that New York State conform to the tax benefits offered by the OZ program. In fact, New York already opted not to follow many other changes included in TCJA, such as the changes to itemized deductions.17 New York also does not follow other areas of federal tax law affecting corporate taxation and treats capital gains income differently from the federal government.

If New York decoupled from the Opportunity Zone program, taxpayers would continue to treat realized gains as income for state and local tax purposes. This would minimize the direct impact on state and local tax revenue from the program.

Conclusion

Economic development spending in New York continues to increase without meaningful improvements in transparency, program design, or performance measurement. The State’s decision to conform to the federal OZ program without imposing additional transparency or accountability measures adds to this trend. Even though New York State and City investors are likely to be among the most significant beneficiaries of the OZ program, the State has yet to pass legislation that would allow the public to understand the cost of the OZ program to State and local governments or the information needed to evaluate whether it makes sense for to conform with the federal program.

Download Report

Opportunity Zones In New York State and CityFootnotes

- To be eligible to receive OZ tax benefits, federal law requires that the investments must be made through Qualified Opportunity Funds (QOF), which are corporations or partnerships organized for the express purpose of investing in opportunity zone projects. QOFs are required to hold 90 percent of their assets in qualified OZ property. QOFs self-certify that they are qualified and in compliance with the 90 percent investment test by attaching a form to their federal income tax returns. See: Internal Revenue Service, “Opportunity Zones Frequently Asked Questions” (July 29, 2019), https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/opportunity-zones-frequently-asked-questions.

- Investors have to hold their investments in a fund for 7 years to get the 15 percent reduction of the deferred gain, and they have to hold for 10 years to get the full exclusion from taxes on appreciated value. Partial benefits are available if investors withdraw their investments early. See: Economic Innovation Group, "The Tax Benefits of Investing in Opportunity Zones" (January 2018), https://eig.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Tax-Benefits-of-Investing-in-Opportunity-Zones.pdf.

- These criteria are derived from another federal place-based community development program, the New Markets Tax Credit, in which the federal government allocates tax credits to community development entities that syndicate the credits and invest the proceeds in businesses and real estate projects in low-income communities. For more information on the NMTC program, see: U.S. Department of the Treasury, CDFI Fund, “New Markets Tax Credit Program Fact Sheet” (January 2018), https://www.cdfifund.gov/Documents/NMTC%20Fact%20Sheet_Jan2018.pdf.

- Some states selected opportunity zones using a transparent, data-driven process that invited comment and public feedback. For example, Colorado’s economic development agency created a statewide metric to evaluate need and investment potential and convened stakeholder groups consisting of local officials, community organizations, and private investors as part of the selection process. California established thresholds for business establishments, poverty rates, and income that exceeded the federal standards, submitted an initial list of census tracts for public comment, and refined its final submission based on feedback it received. See: Colorado Office of Economic Development & International Trade, “Gov. Hickenlooper Announces Opportunity Zone Nominations” (press release, March 23, 2018), https://choosecolorado.com/gov-hickenlooper-announces-opportunity-zone-nominations; and California Opportunity Zones, “Frequently Asked Questions,” https://opzones.ca.gov/faqs.

- The tracts with median family incomes more than $100,000 were located in Downtown Brooklyn, the East Side of Manhattan, and in Buffalo. By 2017, two additional tracts in Red Hook and Bay Ridge neighborhoods of Brooklyn had median family incomes that exceeded $100,000.

- Economic Innovation Group, “Opportunity Zones: Tapping into a $6 Trillion Market” (March 21, 2018), https://eig.org/news/opportunity-zones-tapping-6-trillion-market.

- Novogradac Opportunity Zone Resource Center, “Opportunity Funds Listing” (accessed August 12, 2019), https://www.novoco.com/resource-centers/opportunity-zone-resource-center/opportunity-funds-listing

- Joint Committee on Taxation, Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2018-2022 (JCX-81-18), October 4, 2018, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=download&id=5148&chk=5148&no_html=1.

- Tax Policy Center, “Key Elements of the U.S. Tax System: How are capital gains taxed?” (accessed June 1, 2019), https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/how-are-capital-gains-taxed.

- New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, “Preliminary Report on the Federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act” (January 2018), https://www.tax.ny.gov/pdf/stats/stat_pit/pit/preliminary-report-tcja-2017.pdf.

- Miriam Hall, “Opportunity Zone Investors Weighing Risk vs Social Impact in Program’s Early Days,” Bisnow New York (March 6, 2019), https://www.bisnow.com/new-york/news/opportunity-zones/oz-follow-97841.

- Jamison Dague, Tammy Gamerman, and Elizabeth Lynam, “Bigger Not Better: New York’s Expanding Economic Development Programs” Citizens Budget Commission (February 18, 2015), https://cbcny.org/research/bigger-not-better.

- Mark O’Meara, “Impact Reporting and the Opportunity Zones Incentive,” Novogradac Journal of Tax Credits (May 3, 2019), https://www.novoco.com/periodicals/articles/impact-reporting-and-opportunity-zones-incentive.

- John W. Gahan III, “Industry Has Role to Play in OZ Reporting,” Affordable Housing Finance (May 16, 2019), https://www.housingfinance.com/news/industry-has-role-to-play-in-oz-reporting.

- The U.S. Impact Investing Alliance and the Beeck Center, “Prioritizing and Achieving Impact in Opportunity Zones” (February 2019), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c5484d70b77bd4a9a0e8c34/t/5c61f96ca4222f25386e275a/1549924718674/Opportunity+Zones+Reporting+Framework+-+February+2019.pdf.

- Riley Edwards, “10 Billion Reasons to Rethink Economic Development in New York,” Citizens Budget Commission (February 11, 2019), https://cbcny.org/research/10-billion-reasons-rethink-economic-development-new-york.

- New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, “New York State Decouples from Certain Personal Income Tax Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Changes for 2018 and after” (December 28, 2018), https://www.tax.ny.gov/pdf/memos/income/m18-6i.pdf.