Overboard on OT

Reductions in Uniformed Overtime Needed

While overtime can be a win/win for the employer and employee—providing managers with flexibility and employees with premium pay for extra work—in New York City, overtime is increasingly a fiscal problem as spending rises rapidly, especially among uniformed employees, who receive two-thirds of all overtime pay.

The most recent effort by the City of New York to control uniformed overtime has been to institute caps on city-funded annual uniformed overtime expenditures at the New York Police Department (NYPD), the Fire Department of New York (FDNY), and the Department of Correction (DOC). 1 There is no cap for the Department of Sanitation (DSNY). The caps were set based on recent usage trends and anticipated changes to headcount. Since the majority of all overtime spending is concentrated at the uniformed agencies, this brief will be limited to those agencies.2

Since most changes to address overtime require collective bargaining, and the City is about to embark on another round with the relevant unions, achieving a reduction in uniformed overtime spending should be part of the bargaining pattern. A uniformed labor-management committee, modeled on the collaborative effort between the Municipal Labor Committee and the Office of Labor Relations to develop health savings, could be convened to study the drivers of overtime and propose efforts to reduce the costs by a target percentage.3 While some solutions may be applicable to all uniformed unions, others will need to be tailored by union or by agency.

Overtime Spending Has Exceeded Projections and Grown Sharply

Overtime is hours worked in excess of one’s regularly scheduled workweek, generally more than 40 hours per week. Overtime is usually compensated at 1.5 times the regular rate of pay, though some employees may receive compensatory time (an hour of leave time for each additional hour of work). In addition to federal and state laws that regulate work hours and compensation, labor contracts set overtime parameters for most City employees.

Overtime is beneficial for employers because it provides flexibility, allowing management to respond to bottlenecks, emergencies, and staff absences without hiring new staff. In some instances, consistently high overtime might indicate the need to hire new employees; however, for City workers, especially those in the uniformed services, overtime can be cost-effective because of the high cost of fringe benefits. Fringe benefits, including pensions, exceed 65 percent of base pay for uniformed workers. Therefore, increased uniformed headcount would not necessarily generate savings for the City.

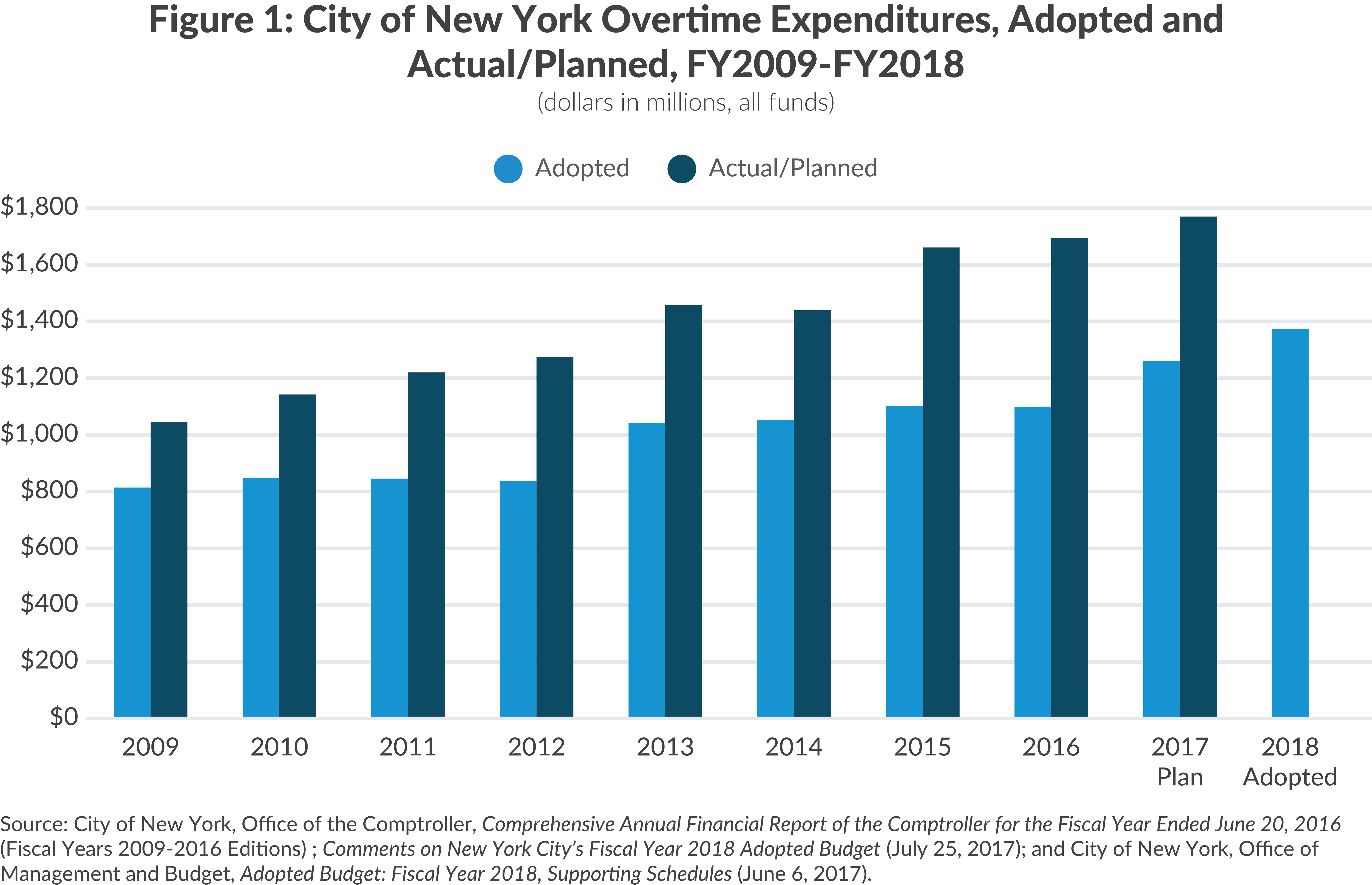

Overtime has exceeded the adopted budget in each of the past nine years by an average 42 percent, ranging from 28 percent in 2009 to 54 percent in 2016. The increase from the adopted budget was $230 million in fiscal year 2009 and reached nearly $600 million in fiscal year 2016; current projections put the fiscal year 2017 overtime budget at $509 million over the adopted amount. This pattern suggests both underfunding of overtime in the adopted budget and inadequate controls on overtime hours during the course of the fiscal year.

The City has increased overtime expense in the Adopted Fiscal Year 2018 budget to $1.4 billion, a nearly 25 percent increase over the Fiscal Year 2016 Adopted Budget. However, given the pattern in recent years, this level is likely to be insufficient; City’s fiscal monitors concur and estimate that the fiscal year 2018 uniformed overtime budget is between $125 million and $169 million too low.4

Growth in overtime is a function of both the number of hours and wage increases. Events and disasters can significantly impact overtime spending; for example, fiscal year 2013 saw a 14 percent increase over 2012, in part due to Superstorm Sandy. From fiscal years 2009 to 2016, overtime spending grew by 7.1 percent a year (See Figure 1); cumulative growth was 62 percent, from just over $1 billion to $1.7 billion.

The fiscal year 2016 spending of $1.7 billion is equal to 8 percent of City’s spending on salaries.5 The New York City Comptroller reported that, as of June 2017, overtime spending for fiscal year 2017 was projected to be $1.8 billion, a 4.5 percent increase over the prior year.6 (A portion of this overtime expenditure is attributable to security at Trump Tower with the City expected to receive Federal funds to cover the expense in part.7)

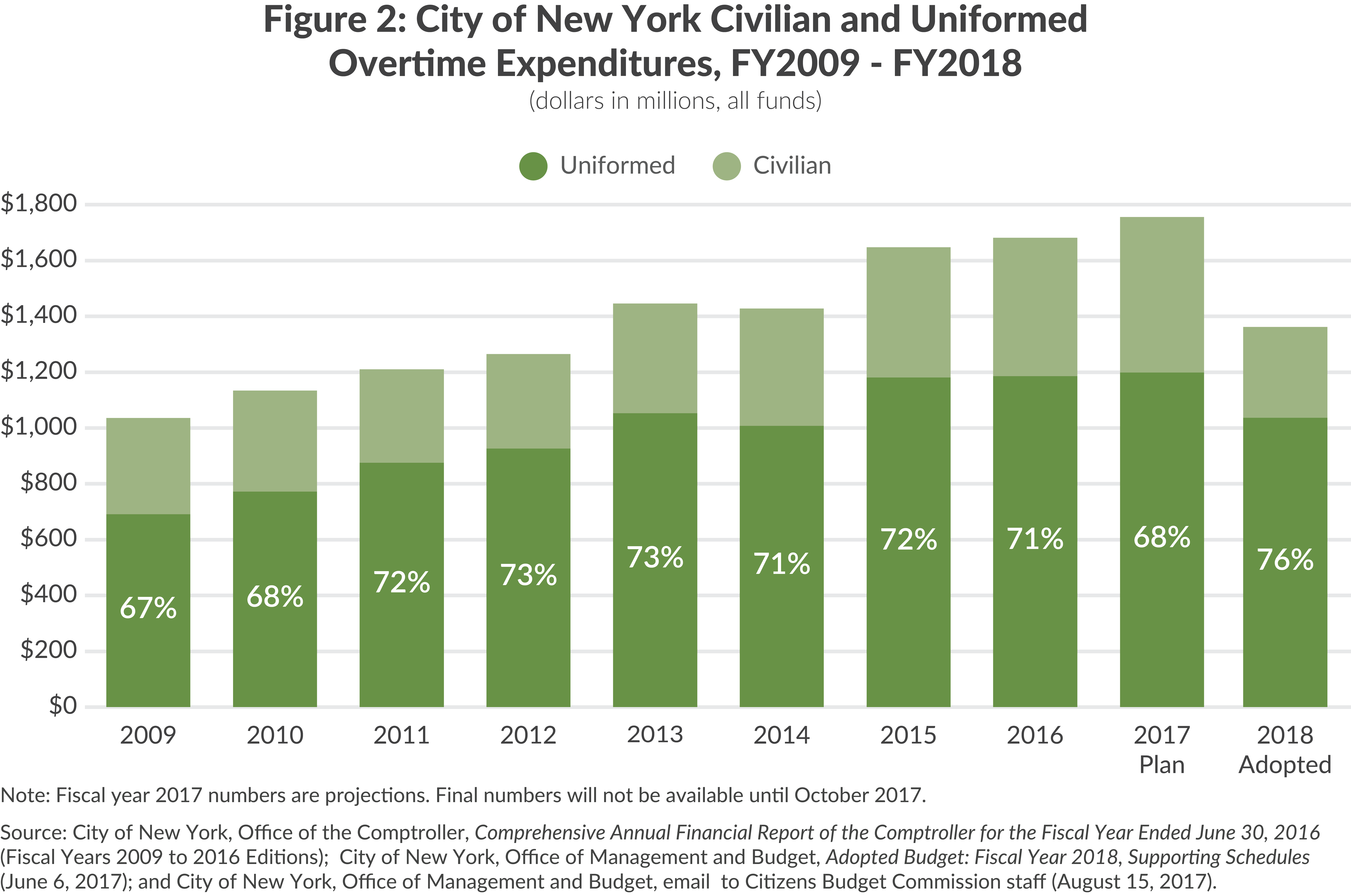

Since 2009 at least two-thirds of all overtime spending has been uniformed overtime, earned by roughly one-fifth of the City’s workforce. (See Figure 2.) From fiscal year 2009 to fiscal year 2016, uniformed overtime grew an average of 8.0 percent a year compared to 5.0 percent a year for civilian overtime; the increase in uniformed overtime was nearly $500 million during that time. For fiscal years 2015 and 2016, uniformed overtime costs have been roughly $1.2 billion a year.

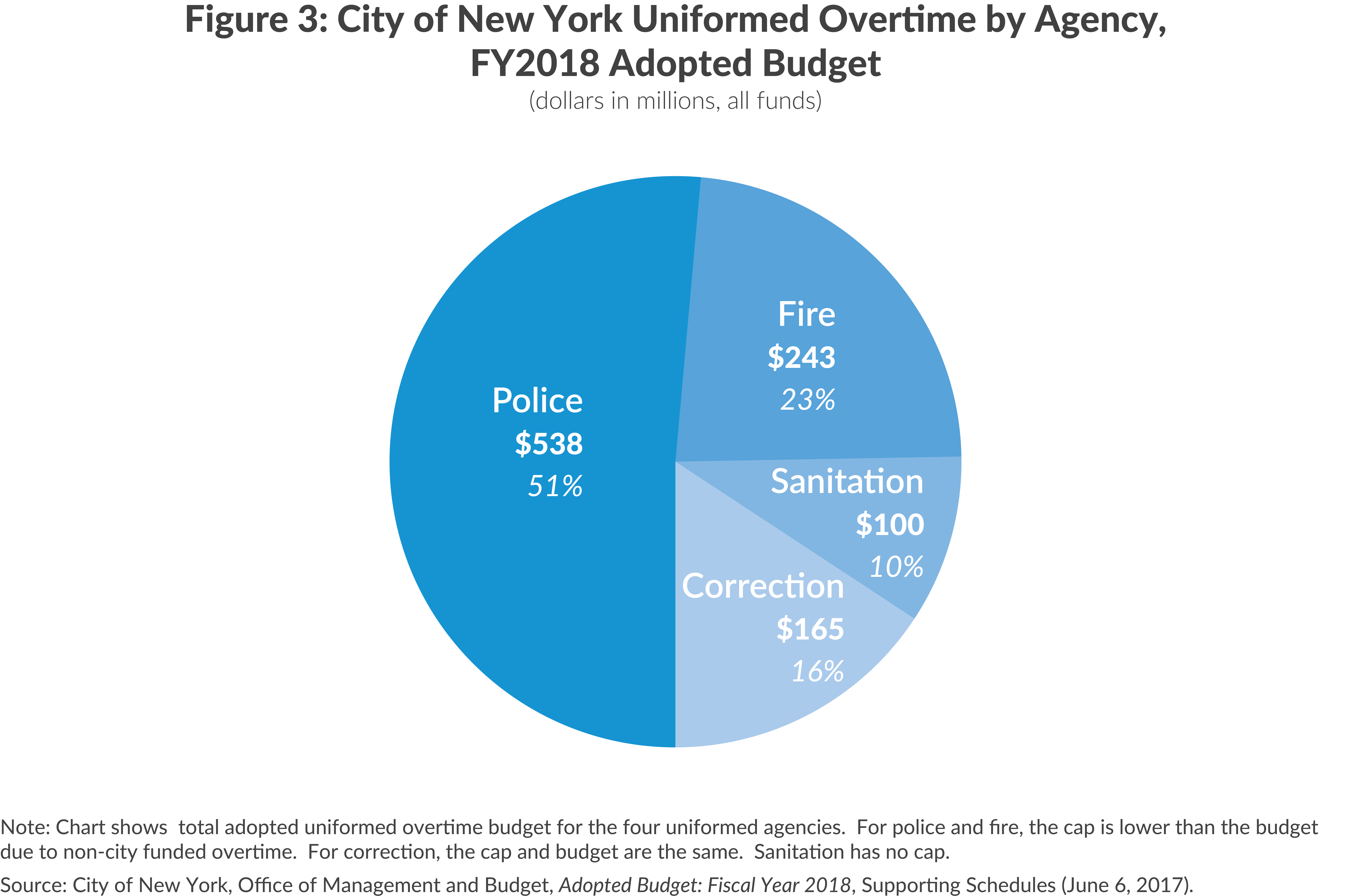

Uniformed overtime in fiscal year 2018 is budgeted at $1.1 billion, about $160 million less than the projection for fiscal year 2017. Figure 3 shows the breakdown for fiscal year 2018 by department. More than half, $538 million, is for the NYPD, and nearly one-quarter, $243 million, is for the FDNY. DOC is budgeted to spend $165 million, or 16 percent, and DSNY is budgeted to spend $100 million, or 10 percent.

Overtime expenses are about 18 percent of regular salaries for uniformed employees in the NYPD and DSNY, 20 percent at DOC, and 26 percent at FDNY; relative to the total departmental budget for salaries and other pay, uniformed overtime remains a substantial share, between 11 and 14 percent.8

Overtime Caps for Three Uniformed Agencies May Be Exceeded

The budgeted decline in uniformed overtime in fiscal year 2018 assumes the successful implementation of overtime caps in three of the four uniformed service agencies. While the caps are an acknowledgement that spending on uniformed overtime must be controlled, they are dollar amounts based on recent usage, trends, and projected increases in uniformed headcount.

In June 2015, as part of negotiations for the Fiscal Year 2016 Adopted Budget, the de Blasio Administration and the City Council agreed to significant new police hiring and an overtime cap for the NYPD.9 At that time the cap was set at $513 million in fiscal year 2016 and $453 million in fiscal year 2017 and beyond.10 However, as one factor in determining the cost of uniformed overtime is the salary of employees, the City has increased the cap to reflect collective bargaining wage increases. Following an arbitration award for 2010 to 2012 and a negotiated contract for 2012 to 2017, the Office of Management and Budget reports that the cap is now $496 million in fiscal year 2017 and $506 million in fiscal year 2018.11

The Preliminary Financial Plan for Fiscal Year 2018 established uniformed overtime caps for FDNY and DOC; the current levels for fiscal year 2018 are $228 million and $165 million, respectively. There is no explicit cap for DSNY.

It is not clear that the NYPD will comply with the cap because the City contends the cap applies only to city-funded overtime and available data do not specify what portion of the uniformed overtime is paid for by non-city funds. The City maintains that the police department conformed to the city-funded cap of $529 million in fiscal year 2016 and will meet the cap in fiscal year 2017. As of June 2017 NYPD uniformed overtime spending for fiscal year 2017 was $581 million (all funds). According to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), the city-funded portion is $496 million, which meets the cap.12

Staying below the overtime caps at FDNY and DOC next year will require significant reductions in spending from the current year. As of June 2017 fiscal year 2017 city-funded FDNY uniformed overtime was $263 million according to OMB, while city-funded uniformed overtime at the correction department reached $231 million, both in excess of prospective fiscal year 2018 caps.13

Drivers of Overtime at Uniformed Agencies

Unexpected events, work culture, collective bargaining rules, and aspects of uniformed agency staffing and workload contribute to the high rate of overtime. Some of these factors apply to all four uniformed agencies, while others are applicable to only some agencies.

Unexpected events or circumstances can require use of significant overtime in the short-term. For example, NYPD, FDNY, and DSNY all incurred significant overtime following Superstorm Sandy and the need to provide enhanced protection at Trump Tower drove up NYPD and FDNY overtime in fiscal year 2017.

A culture of working overtime exists at many agencies and employees expect the bump in earnings. In fiscal year 2016 53 percent of uniformed employees received overtime that exceeded 20 percent of their base pay and 6 percent (over 3,800 employees) exceeded 50 percent of their base pay. Nearly $1.2 billion in overtime compensation was paid to roughly 63,000 uniformed employees—about $19,400 per employee.14

Collective bargaining agreements between the City and the uniformed labor unions often limit the ability of managers to alter schedules and work assignments.15 For example, contract provisions generally prohibit changes to tours or shifts “in order to preserve spirit” of overtime.16 Some contracts require minimum overtime hours for employees called in to work, or guarantee overtime pay for travel time to assignments other than the employee’s permanent location.17

The uniformed agencies, except for the NYPD, rely on fixed post staffing, which means that a minimum number of staff must be on duty to fill the positions. Fixed post staffing contributes to overtime in two ways: coverage for vacant positions and filling in for staff out on leave.

First, if the agency is understaffed due to high rates of turnover or a large number of vacant positions, existing staff will be called in on overtime to meet staffing needs. As the process for hiring employees is lengthy, this can significantly impact overtime.18 Most of the uniformed agencies hire in classes, meaning a large group of entry-level employees is hired at once and undergoes training prior to being assigned to posts.

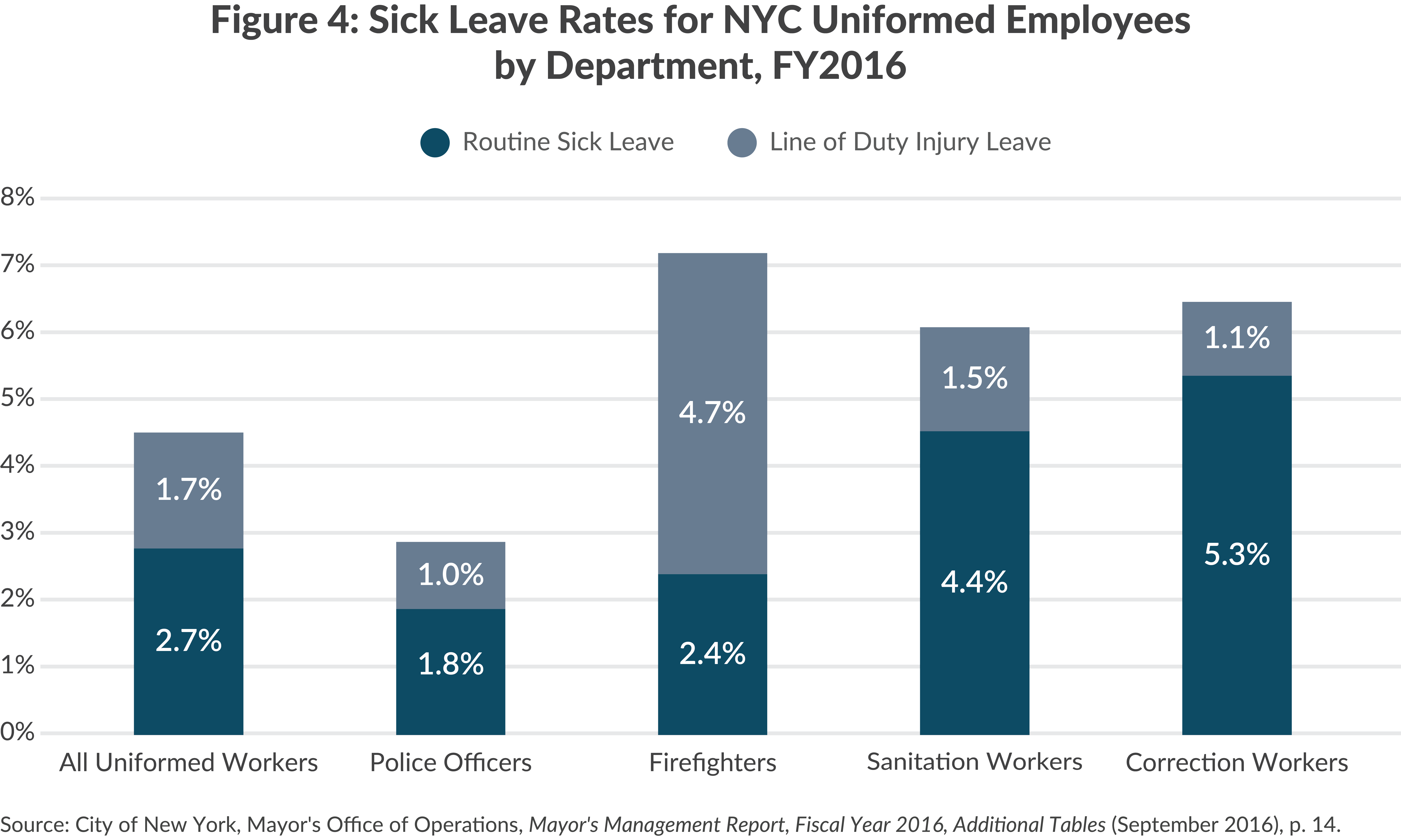

Second, high rates of absenteeism can exacerbate the use of overtime and the collective bargaining contracts for uniformed employees provide unlimited sick leave. 19 As shown in Figure 4, in fiscal year 2016 the sick leave rate for line-of duty injuries (LODI leave) was 1.7 percent for all uniformed employees, while the routine sick leave rate (for non-work related illness) was 2.7 percent, for a combined sick leave rate of 4.4 percent.20 However, there is considerable variability among the uniformed agencies.

Police Department

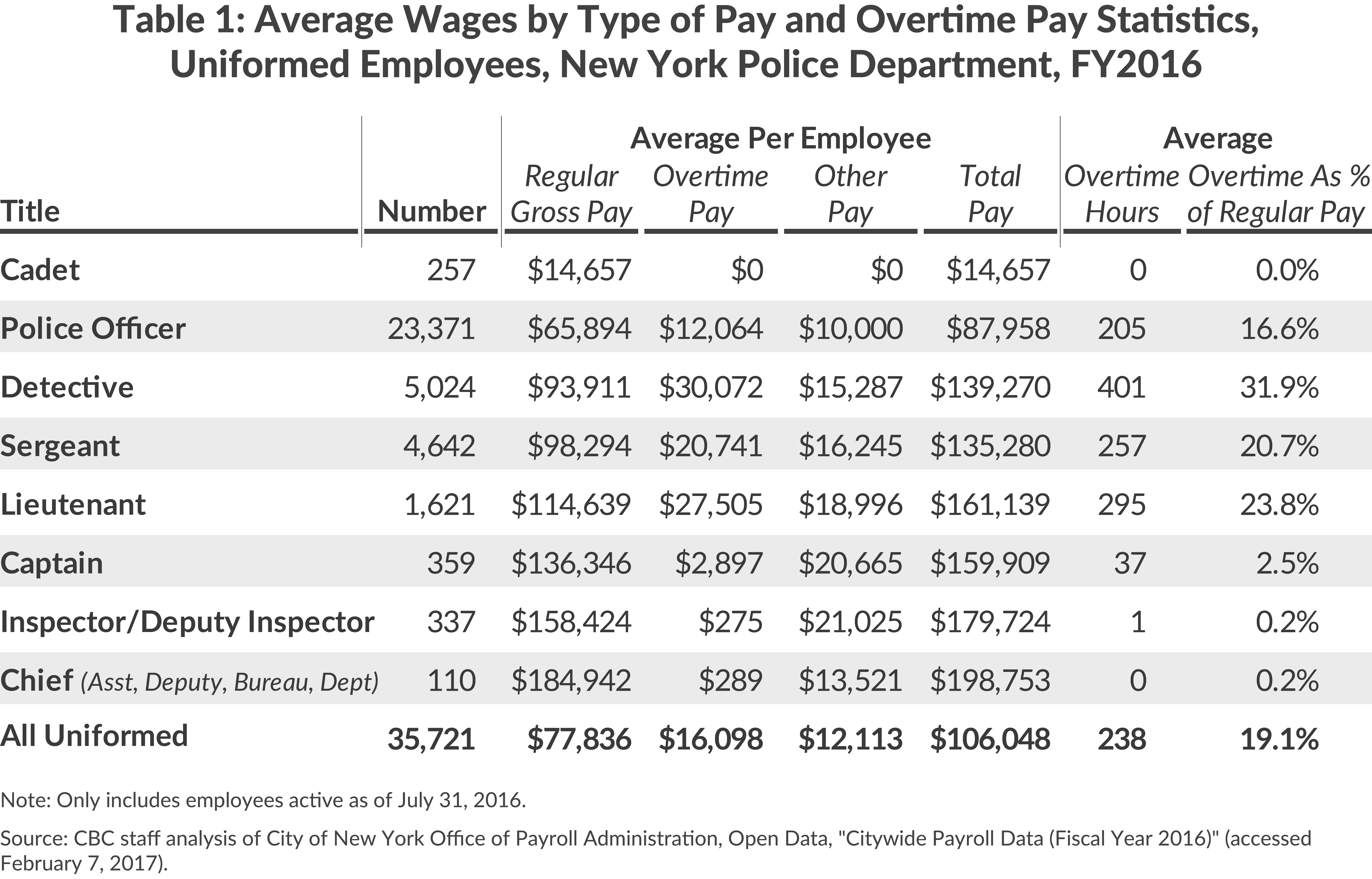

While there is some variation by title, all uniformed NYPD employees in ranks through that of lieutenant earn substantial overtime. (See Table 1.) Detectives earn the most on average, about $30,000 a year in fiscal year 2016, working 401 hours of overtime a year. Lieutenants, who are often supervising investigations or a bureau, squad, or unit, average 295 hour of overtime a year, earning nearly $28,000 in overtime compensation. Sergeants, who supervise patrol officers, average 257 hours of overtime and receive more than $20,000 in overtime pay. Police officers clock in more than 200 hours of overtime each year, earning about $12,000 in overtime pay on average. Generally, captains and higher ranks are ineligible for overtime.21

Unlike the other uniformed agencies, the police department is not staffed based on fixed posts. The department has more flexibility in staffing assignments and while officers are assigned to precincts or special units, these units don’t have fixed staffing ratios. Furthermore, absenteeism is not a driver of overtime as the rate at NYPD is the lowest of the uniformed agencies. (See Figure 4.)

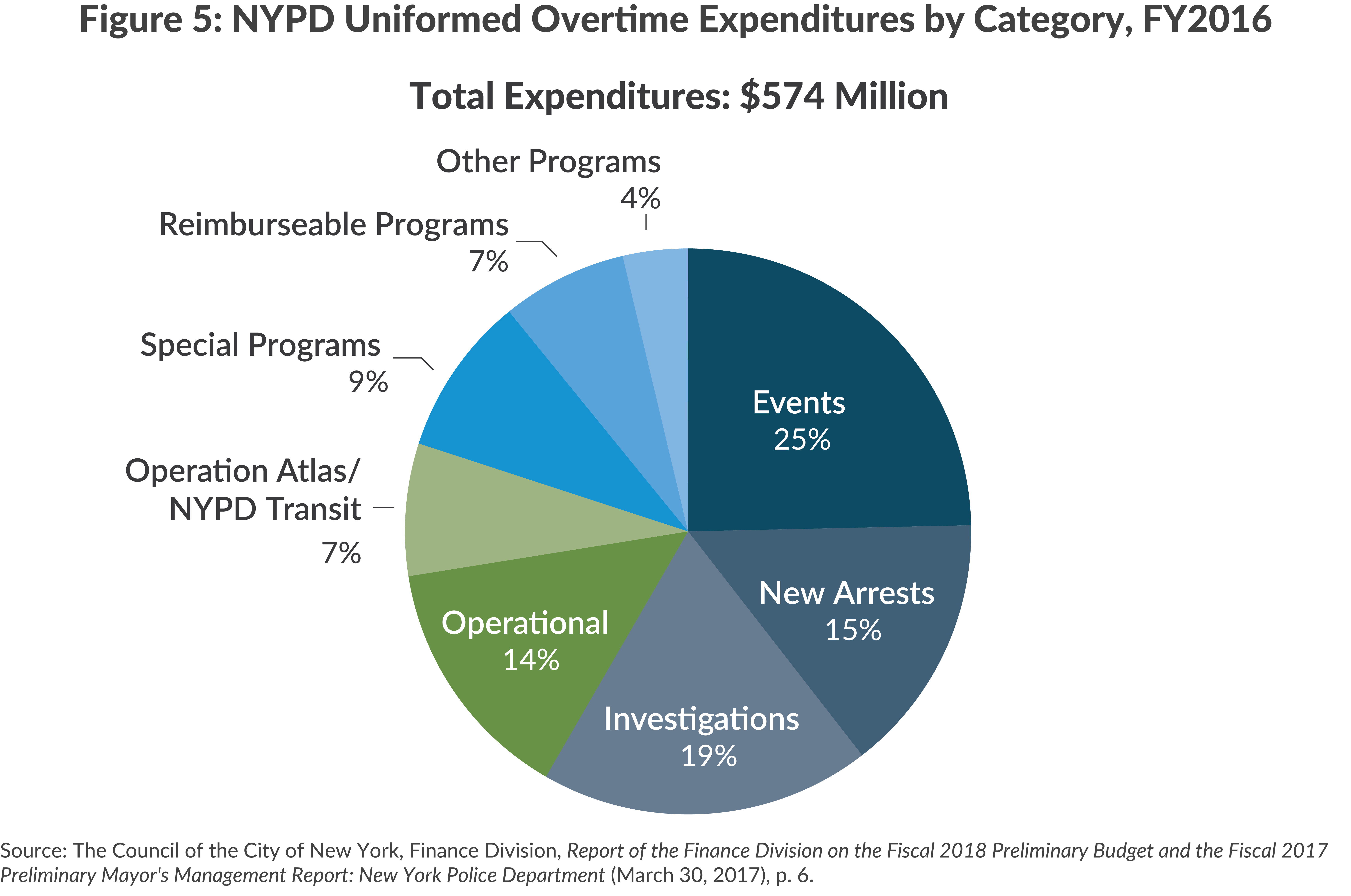

Three causes of police department overtime stand out. (See Figure 5.) The first is special events, which accounted for one-quarter of the uniformed overtime in fiscal year 2016. This category includes overtime related to parades, which are fairly consistent from year to year. Less consistent are emergencies and other unanticipated events that generate overtime, such as Trump Tower security, Occupy Wall Street, and Superstorm Sandy. While the nature and timing of these events is unpredictable, the City can count on a certain amount of overtime due to unplanned events and emergencies each year. Investigations (19 percent) and new arrests (15 percent) are two other areas that significantly contribute to overtime. Both categories are driven by the need to extend the workday in order to complete police work.

Fire Department

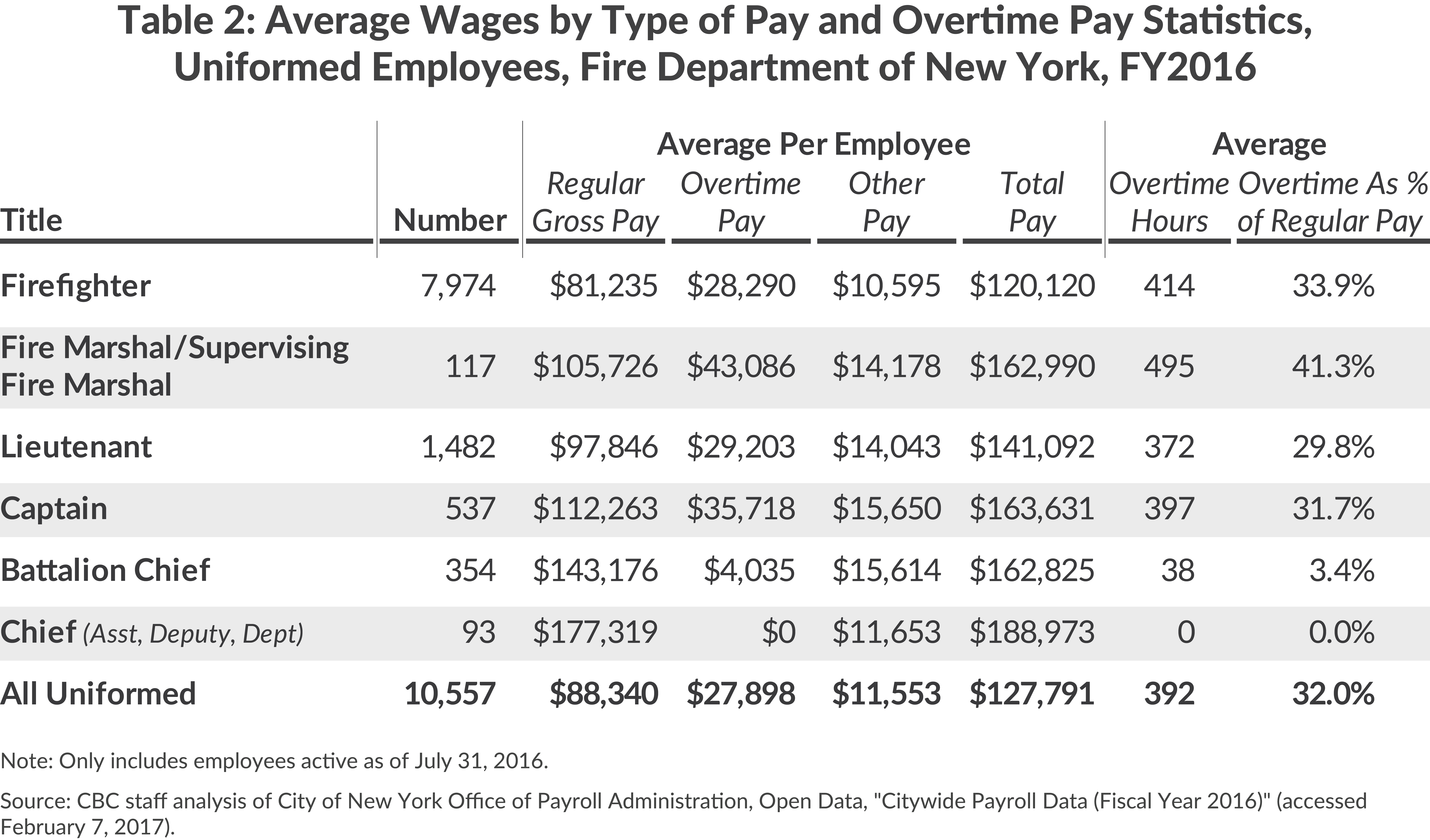

Payroll data bear out the high use of overtime at the FDNY. (See Table 2.) Firefighters, lieutenants and captains worked between 372 and 414 overtime hours, on average, in fiscal year 2016. The average increase in compensation was between $28,000 for firefighters and $36,000 for captains, approximately one-third of the regular pay. Fire marshals had even higher rates, but there were significantly fewer on staff. Battalion chiefs and chiefs do not generally receive overtime compensation.

Staffing and work rules significantly impact FDNY overtime. The labor contract guarantees 96 hours of roster (scheduled) overtime each year.22

Staffing at FDNY is based on fixed posts. There are six types of companies, though most are engine or ladder companies.23 Currently, the City has 198 engine companies, which operate fire engines that secure water and extinguish the fire. An additional 143 ladder companies operate fire trucks that are responsible for search and rescue, entry, and ventilation at a fire. Staffing for engine companies is 4 or 5 firefighters and 1 officer, while ladder companies are staffed with 5 firefighters and 1 officer. Because the City is required to maintain these staffing ratios if a firefighter is unable to report to duty, the department must call in a firefighter (generally on overtime) to cover the post.

Decreasing headcount at the department contributed to an increase in overtime. (See Figure 6.) In 2007 a lawsuit was filed alleging discrimination in FDNY hiring.24 While this litigation was pending, the department was prohibited from hiring and there were no new firefighter classes from July 2008 until January 2013.25 Due to employees leaving the department for reasons such as retirement or resignation, uniformed headcount decreased from 11,459 at the end of fiscal year 2009 to 10,180 at the end of fiscal year 2013, an 11 percent decline. Concurrently, the use of overtime to maintain staffing ratios more than doubled, going from $128 million to $280 million. FDNY hiring has resumed, and uniformed headcount increased nearly 8 percent from fiscal year 2013 to fiscal year 2016; however, overtime spending decreased just $3 million over that time period.26

Firefighter schedules are based on groups which are scheduled to work either 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. or 6 p.m. to 9 a.m. (a 9-hour day shift and a 15-hour night shift). Based on the official schedule, a group would be on for two consecutive 9-hour shifts, off for two days, on for two consecutive 15-hours shifts, than off for three days, before repeating the cycle.27 Shift changes at 6 p.m. can increase the use of overtime because these are fairly busy times for the FDNY; some cities with 24-hour shifts have one shift change in the morning, thereby avoiding the busy 6 p.m. period.28

Absenteeism is also a major factor. Uniformed firefighters have the highest rate overall, at 7 percent; due to the nature of the work, two-thirds of the sick leave is attributable to work-place related injuries. (See Figure 4.) An analysis by the New York City Independent Budget Office for fiscal year 2016 found that among uniformed FDNY employees, 31 percent used no sick leave, 26 percent were only out for line of duty injury sick leave, and the remaining 43 percent were responsible for all of the routine sick leave.29 Furthermore, the analysis found that the top 10 percent of sick leave users were responsible for nearly 60 percent of the agency’s routine sick leave.

Department of Correction

Like the FDNY, much of the staffing at DOC is based on fixed posts. There are minimum staffing needs at each facility and unit, and a minimum number of officers are needed for functions like inmate transportation to courts, and medical emergencies. While the inmate population has declined substantially in recent years, the City has increased staffing needs to address high rates of violence and maltreatment.30

According to data from DOC, 65 percent of overtime in fiscal year 2017 is scheduled overtime for regular posts. Other reasons include overtime related to construction work (7 percent), medical transport (5 percent), staff shortage (3 percent), and suicide watch (3 percent).31

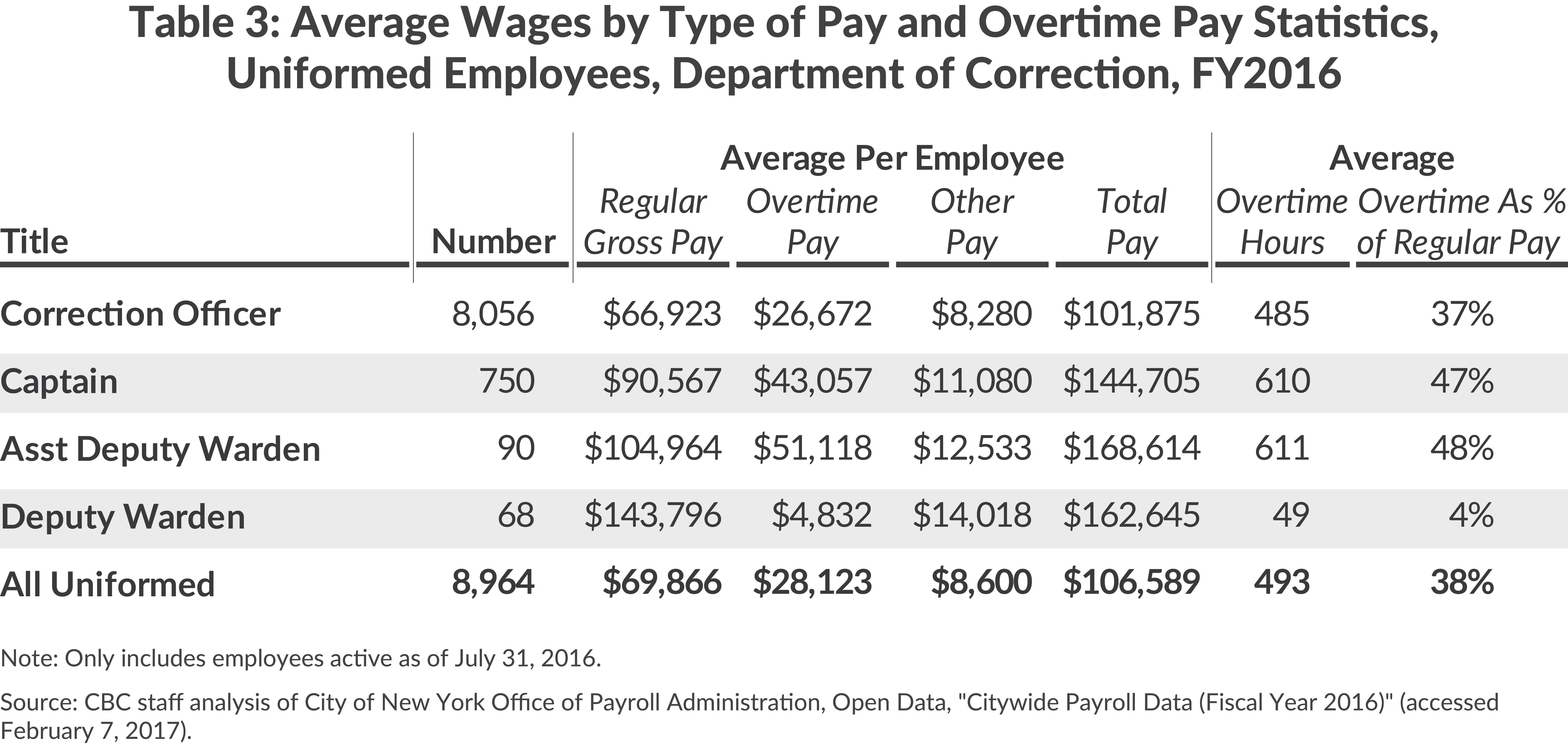

Average overtime hours and earnings at DOC were higher than in the other uniformed departments in fiscal year 2016. (See Table 3.) Furthermore, higher ranking uniformed officers generally work more overtime. Captains and Assistant Deputy Wardens averaged 610 hours of overtime (nearly 12 hours a week), with average overtime pay of $43,000 and $51,000 a year, respectively. While Correction officers work less overtime than supervisors, they still exceed other uniformed titles at 485 hours a year, on average.

Staffing and absenteeism are challenges for the department. Hiring has not kept up with uniformed vacancies and the department has been expanding its capacity to train new classes of officers.32 Additionally, turnover and dismissal rates are higher than in other uniformed departments. In fiscal year 2015 7.1 percent of corrections officers left the department (including retirements) compared with rates between 3.3 percent and 4.3 percent for police officers, firefighters, and sanitation workers.33 Data on the reason why employees left shows higher rates of dismissal in DOC than the other uniformed agencies.34 In addition, as Figure 4 shows, uniformed DOC employees have high rates of sick leave usage. The overall rate is 6.4 percent: LODI-related sick leave is 1.1 percent while routine sick leave is 5.3 percent.

Department of Sanitation

Overtime at DSNY is very much a function of weather and snow-removal activities. (See Figure 7.) Non-snow overtime has ranged from $31 million to $62 million, with an exception in fiscal year 2013 when debris removal following Superstorm Sandy increased non-snow overtime to $85 million. Overtime related to snow removal activities is directly related to the number and severity of winter storms—from a low of $7 million in fiscal year 2012 to a high of $60 million in fiscal year 2014.

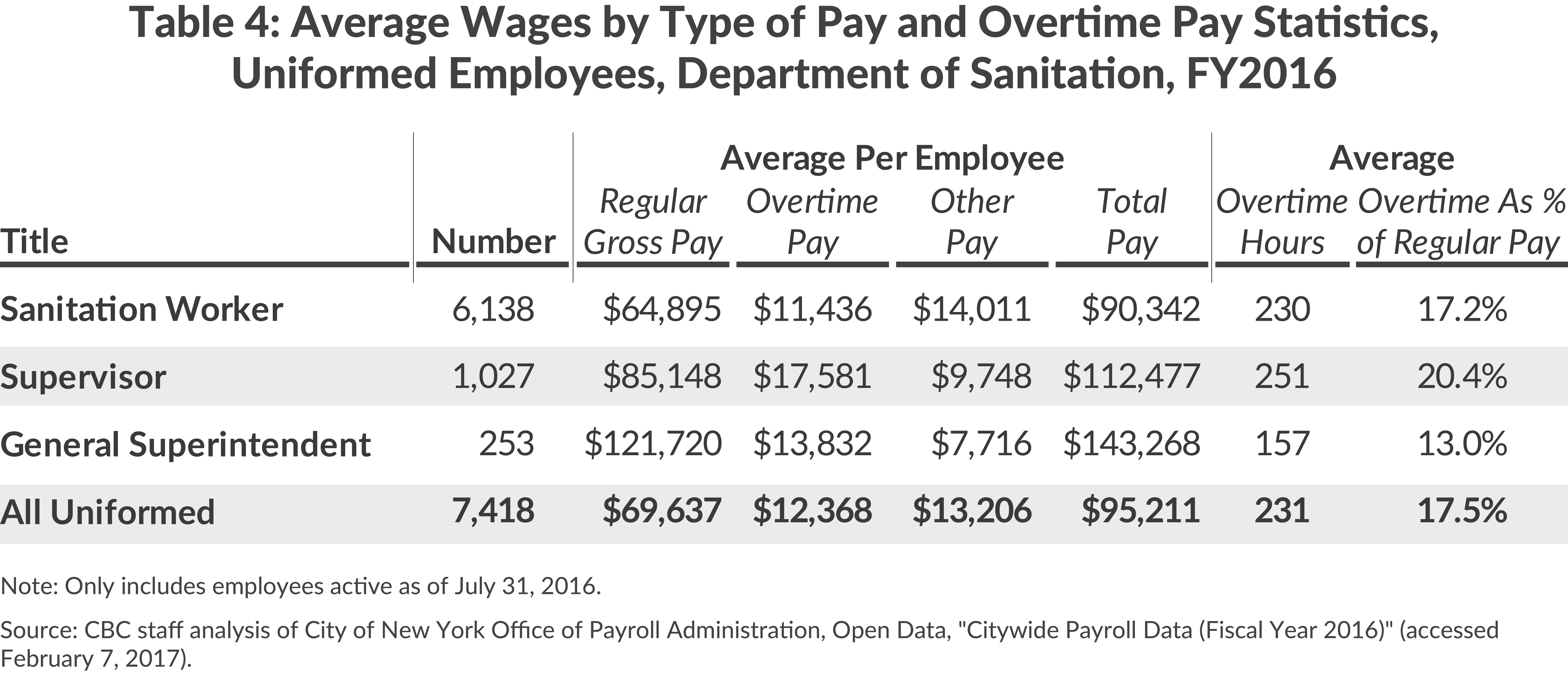

Sanitation workers average between 157 hours of overtime for general superintendents and 251 hours for supervisors, increasing average pay by about $14,000 and $17,500, respectively. (See Table 4.) Front-line sanitation workers average 230 hours a year, earning approximately $11,500 in overtime pay.

Recommendations

With uniformed overtime continuing to grow and previous efforts to control costs falling short, the City should establish a uniformed labor-management committee as part of the next round of collective bargaining in order to reduce uniformed overtime spending. The City’s recent experience with healthcare savings shows that bringing both sides to the table can be an effective tool to resolve fiscal challenges across a number of agencies.

Employees and their supervisors are in the best position to devise proposals to reduce uniformed overtime. Some ideas that should be considered include:

- Adopting a system in which routine sick leave usage is accrued and capped (as for NYC civilian employees). The high rates of routine sick leave, especially when concentrated among a small set of uniformed employees, call for greater oversight.

- Changing certain work rules, such as eliminating overtime for travel to alternate work locations, and guaranteed minimum overtime hours. Minimum staffing levels could also be altered.

- Instituting a per employee cap on overtime hours or overtime earnings, as exists for civilian employees.

- Capping or eliminating overtime earnings in calculating final average salary for pensions.35 The cap would require State legislative approval. As it would only apply to new hires, the City would not realize significant savings for many years.

Conclusion

Uniformed overtime remains a significant fiscal challenge for the City’s budget. If the caps instituted by the de Blasio Administration are to be achieved, more concerted, systemic efforts to directly address the reasons for the high overtime must be made. A labor-management committee should be established to negotiate a set a of work policy reforms to reduce overtime as part of the next round of collective bargaining.

Download Report

Overboard on OT: Reductions in Uniformed Overtime NeededDownload Appendix

Average Wages and Overtime Pay Statistics, Uniformed Employees, FY2016Footnotes

- All caps are based on city-funded uniformed overtime expenditures.

- The City is pursuing efforts to curtain civilian overtime as well, with a number of initiatives introduced as part of the Citywide Savings Plan. These include greater oversight of the civilian overtime cap; a cap on skilled trades’ overtime; and a centralized pool of skilled trades workers that can be deployed to specific agencies to address work needs and backlogs. See City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Executive Budget: Fiscal Year 2018, Citywide Savings Program (April 26, 2017), p. 8, http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/csp4-17.pdf.

- Alternatively, the City could set overtime reduction targets for individual uniformed bargaining units as a condition of getting a higher uniformed pattern of wage increases.

- New York State Financial Control Board, Review of the FYs 2018-2021 Financial Plan: Staff Report (July 26, 2017), p. 5, www.fcb.state.ny.us/pdf/FCBNY20170726_StaffReport.pdf; Office of the New York State Comptroller, Review of the Financial Plan of the City of New York (August 2017), p. 6, www.osc.state.ny.us/osdc/rpt3-nyc-2018.pdf; and Office of the New York City Comptroller, Comments on New York City’s Fiscal Year 2018 Adopted Budget (July 25, 2017), p10, http://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/Comments-on-New-York-Citys-Fiscal-Year-2018_AdoptedBudget.pdf.

- Includes all funds. City of New York, Office of the Comptroller, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report of the Comptroller for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2016, pp. 312-313, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/CAFR2016.pdf.

- Final audited financial data for fiscal year 2017 will not be available until release of the Comprehensive Annual Financial Report on October 31, 2017.

- Available data do not indicate the amount of NYPD overtime spent on Trump Tower security or the amount to be reimbursed by the Federal government. The City reported that NYPD overtime was $23.8 million from the election to the inauguration; the department estimated overtime through the end of the fiscal year would run $42.5 million. See Testimony of Vincent Grippo, Deputy Commissioner, New York City Police Department, before the City Council of the City of New York Committee on Finance Jointly with Committee on Public Safety (May 22, 2017), p. 48, http://legistar.council.nyc.gov/View.ashx?M=F&ID=5304013&GUID=4EFE669E-82CB-4097-86AD-61695372EFBE.

- Salaries and other pay includes base salary, overtime, differentials such as longevity and shift differential, and other pay, such as holiday pay, for uniformed and civilian employees at the department. CBC staff analysis of City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Open Data, "Expense Budget" (accessed June 14, 2017), https://data.cityofnewyork.us/City-Government/Expense-Budget/mwzb-yiwb.

- City of New York, Office of the Mayor, “Mayor de Blasio, Speaker Mark-Viverito, City Council Reach Early Agreement on Balanced FY2016 Budget” (press release, June 22, 2015), http://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/432-15/mayor-de-blasio-speaker-mark-viverito-city-council-reach-early-agreement-balanced-fy2016-budget#/0

- The mechanics of setting the cap in the budget were to increase city-funded uniformed police overtime to a level roughly in-line with the average for the preceding four years: $530 million in fiscal year 2016 and $516 million in fiscal years 2017 to 2020. The City then made a second adjustment to reflect the expected decrease in uniformed overtime due to the cap, which included the impact of hiring new officers. The City estimated a reduction of $16 million in fiscal year 2016 and $63 million a year going forward. See The Council of the City of New York, Report on the Fiscal 2017 Preliminary Budget and the Fiscal 2016 Preliminary Mayor’s Management Report: New York Police Department (March 21, 2016), https://council.nyc.gov/budget/wp-content/uploads/sites/54/2016/05/056-NYPD.pdf

- City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, email to Citizens Budget Commission staff (June 4, 2017). The City has not published the revised overtime cap figures nor the method for determining the increase. Note that for the police department, the cap is for city-funded uniformed overtime, while the total uniformed overtime budget includes non-city funds, which explains why the cap is $506 million and the total uniformed overtime in Figure 3 is $538 million.

- City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, email to Citizens Budget Commission staff (August 14, 2017). This number is subject to change as the final audited financial statements will not be available until October 2017.

- City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, email to Citizens Budget Commission staff (August 15, 2017). According to OMB, total uniformed overtime will be $272 million at FDNY and $240 million at DOC.

- CBC staff analysis of City of New York Office of Payroll Administration, Open Data, "Citywide Payroll Data (Fiscal Year)" (Accessed February 7, 2017). Includes employees on active status as of July 31, 2016.

- CBC staff contract analysis based on review of recent labor contracts with the following unions: Correction Officer’s Benevolent Association, Correction Captains Associations, Assistant Deputy Wardens Association, Uniformed Firefighters Association, Uniformed Fire Officers Association, Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, Sergeants’ Benevolent Association, Lieutenants’ Benevolent Association, Captains’ Endowment Association, Uniformed Sanitationmen’s Association, Sanitation Officers Association, and the Uniformed Sanitation Chiefs Association. See City of New York, Office of Labor Relations, “Collective Bargaining: Past Agreements – Uniformed Contracts” (accessed August 4, 2017), http://www1.nyc.gov/site/olr/labor/labor-recent-agreements.page; and City of New York, Office of Labor Relations, “Collective Bargaining: Recent Agreements & Prevailing Rate Consent Determinations” (accessed August 4, 2017), http://www1.nyc.gov/site/olr/labor/labor-uniformed-contracts.page.

- For example, the contract between the City of New York and the Correction Officers Benevolent Association says “In order to preserve the intent and spirit of this Section on overtime compensation, there shall be no rescheduling of days off and/or tours of duty.” See City of New York, Office of Labor Relations, Executed Contract: Correction Officers: Term: November 1, 2011 to February 28, 2019 (January 6, 2017), p. 3, http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/olr/downloads/pdf/collectivebargaining/coba-final-agreement-2011-2019.pdf.

- These provisions are found in many of the uniformed contracts. Two examples from the contract between the City of New York and the Uniformed Firefighters Association are: 1) “When Firefighters are not continued on duty but are ordered to report for emergency duty from a scheduled off tour or a scheduled rest period, they shall be compensated for a minimum of four hours if not assigned to duty and for a minimum of six hours if assigned to duty. Such compensation shall be by cash payment at the rate of time and one-half based on the regular salary for Firefighters” (Article III, Section 3, p. 2); and 2) “In the event that a Firefighter or Fire Marshal is detailed to a unit other than the unit to which that employee is permanently assigned, if the employee is required to report at the other unit at the start of a respective tour (e.g., 0900, 1800, etc.), that employee shall receive compensation for travel to the unit to which that employee is detailed at the rate of time and one-half for 45 minutes of travel time if the detailed unit is within the same borough as that employee’s permanent unit or 1-1/4 hours if the detailed units is in a different borough than that of the employee’s permanent unit.” (Article XXIII, Section 1.A, p. 26). See City of New York, Office of Labor Relations, Executed Contract: Firefighters: Terms: August 1, 2008 to July 31, 2010 (November 23, 2009), p. 2 and p. 26, http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/olr/downloads/pdf/collectivebargaining/cbu41-fire-uniformed-080108-to-073110.pdf.

- For example, in the Department of Correction employees file to take a written exam; sit for the exam; wait for the exam to be graded; undergo a medical exam; complete a background investigation; undergo a psychological exam; take a agility test; and attend and complete a 5-month training at the Academy prior to starting work as a Correction Officer. See New York City Department of Correction, Candidate Journey (accessed July 27, 2017), http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/jointheboldest/downloads/pdf/Candidate_Journey.pdf.

- Uniformed employees receive unlimited sick leave for both line of duty injuries and illness/injury unrelated to their employment. Uniformed agencies have policies regarding sick leave usage and monitoring usage to limit abuse. City of New York, Office of Labor Relations, Executed Contract: Police Officers: Term August 1, 2010 to July 31, 2012 (February 26, 2016), Article X. Section 1.a., p. 9, http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/olr/downloads/pdf/collectivebargaining/Police-Officers-08-01-2010-07-31-2012.pdf.

- City of New York, Mayor's Office of Operations, Mayor's Management Report, Fiscal Year 2016, Additional Tables (September 2016), p. 14, http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/operations/downloads/pdf/mmr2016/full_report_additional_tables_2016.pdf.

- Due to challenges in recruiting captains because the loss of overtime pay generally results in lower total compensation after promotion, the City negotiated changes in the labor contract to allow newly promoted captains to receive overtime for up to 180 hours a year. See Larry Celona, “NYPD offering $10K in overtime to increase number of captains” (October 1, 2015), New York Post, http://nypost.com/2015/10/01/nypd-offering-10k-in-overtime-to-increase-number-of-captains.

- City of New York, Office of Labor Relations, Executed Contract: Firefighters: Terms: August 1, 2008 to July 31, 20010 (November 3, 2009), p. 68, http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/olr/downloads/pdf/collectivebargaining/cbu41-fire-uniformed-080108-to-073110.pdf.

- The other four types of companies are: rescue companies (5), squad companies (7), marine/fireboat companies (3), and the HazMat unit (1). The department has other special units.

- United States and Vulcan Society v. City of New York.

- City of New York, Office of Payroll Administration, Open Data, “Citywide Payroll Data (Fiscal Year 2016)” (accessed February 7, 2017).

- One reason for the minimal decline in overtime spending is higher salaries for uniformed FDNY employees following collective bargaining increases.

- Many firefighters routinely switch shifts with other firefighters to be on duty for 24 hours and then off for a longer stretch.

- In New York City, nearly 15 percent of calls for structural fires are between 5:00 p.m. and 7 p.m., the highest frequency of any two hour window. In Houston, for example, a shift change occurs at 6:30 a.m. and in Chicago at 8 a.m. See: CBC staff analysis of Fire Department of New York City, Open Data, “Fire Incident Dispatch Data” (accessed July 18, 2017); City Of Houston, Houston Fire Department: Firefighters Shift Calendar (accessed August 4, 2017), www.houstontx.gov/fire/firefighterinfo/shifts.html; and City of Chicago, Labor Contract Between Chicago Fire Fighters Union, Local No 2, and the City of Chicago, Illinois: July 1, 2012 – June 30, 2017, p. 10, www.cityofchicago.org/content/dam/city/depts/dol/Collective%20Bargaining%20Agreement3/POLICEFIRE-Local2CBA2012-2017final.pdf.

- Bernard O’Brien, “How Does Sick Leave Usage Vary Across the City’s Workforce” (October 25, 2016), NYC By the Numbers, NYC Independent Budget Office, http://ibo.nyc.ny.us/cgi-park2/2016/10/how-does-sick-leave-usage-vary-across-the-citys-workforce.

- Shannon Hakh, Focus on: The Preliminary Budget: Overtime for Correction Officers Continues to Increase (New York City Independent Budget Office, March 2017), www.ibo.nyc.ny.us/iboreports/overtime-for-correction-officers-continues-to-increase-march-2017.pdf.

- The Council of the City of New York, Report of the Finance Divisions on the Fiscal 2018 Preliminary Budget and the Fiscal 2017 Preliminary Mayor’s Management Report: Department of Correction (March 9, 2017), p. 7, http://council.nyc.gov/budget/wp-content/uploads/sites/54/2017/03/072-DOC.pdf.

- The DOC academy class sizes have been increasing to meet hiring needs, from about 300 recruits to 600 recruits, with the December 2016 class reaching 929 recruits. See The Council of the City of New York, Report of the Finance Divisions on the Fiscal 2018 Preliminary Budget and the Fiscal 2017 Preliminary Mayor’s Management Report: Department of Correction (March 9, 2017), http://council.nyc.gov/budget/wp-content/uploads/sites/54/2017/03/072-DOC.pdf. Additionally, the City has announced $100 million in capital funding for a new training academy for the department. See City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Executive Budget: Fiscal Year 2018, Message of the Mayor (April 26, 2017), p.105, http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/mm4-17.pdf.

- New York City Department of Citywide Administrative Services, NYC Government Workforce Profile Report (Fiscal Year 2015), http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcas/downloads/pdf/misc/workforce_profile_report_fy_2015.pdf.

- Separation reason is not available by title, but rather for the entire agency. Dismissals were 13 percent of all DOC separations, compared with 6 percent at DSNY, 4 percent at FDNY and 4 percent at NYPD. See New York City Department of Citywide Administrative Services, NYC Government Workforce Profile Report (Fiscal Year 2015), http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcas/downloads/pdf/misc/workforce_profile_report_fy_2015.pdf.

- Current policy incentivizes an uptick in overtime prior to retirement. Actuarial assumptions for the police and fire pension funds assume a higher overtime rate at 20 years. See New York City Police Pension Fund, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report: A Pension Trust Fund for the City of New York: For the fiscal years ended June 30, 2016 and June 30, 2015, p. 213, www.nyc.gov/html/nycppf/downloads/pdf/CAFR%202016.pdf; and New York Fire Department Pension Funds, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report: A Pension Trust Fund of the City of New York: For the Fiscal Years Ended June 30, 2016 and June 30, 2015, p. 149, http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/fdny/downloads/pdf/about/fire-pension-fund-cafr-2016.pdf.