The Challenge of Staying Under the 2 Percent State Spending Cap

New York State’s leaders deserve credit for keeping state-financed budget growth below a self-imposed 2 percent spending cap since fiscal year 2011, a sharp departure from historical norms. The discipline has markedly improved the State’s fiscal condition and spurred key reforms in Medicaid and State operations.

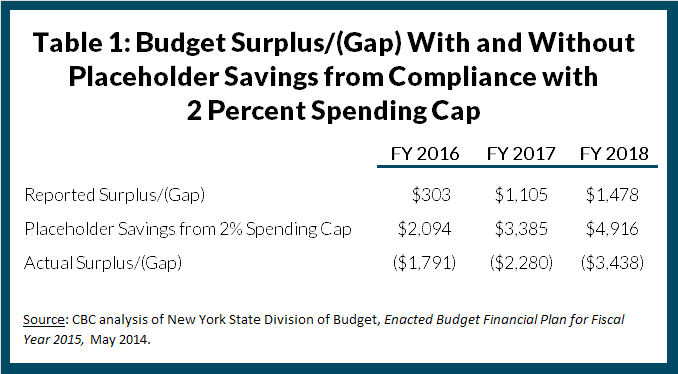

But now the enthusiasm for spending control is starting to exceed what is realistic. The Enacted Budget report released on May 9 continues the device that first appeared in the Executive Budget of plugging gaps in future years with unspecified “future savings” ranging from $2.1 billion in fiscal year 2016 to $4.9 billion in fiscal year 2018. (See Table 1.) In reality the State faces budget gaps that grow from $1.8 billion to $3.4 billion by fiscal year 2018 that will need to be closed with concrete savings plans. With large parts of the budget, including school aid and Medicaid, growing at rates of 4 to 5 percent annually reaching the savings targets will require sizeable cuts in spending elsewhere in the budget. School aid and Medicaid could also be cut, although separate statutory caps set at rates higher than 2 percent and prior commitments in these two areas of the budget make it more difficult to reduce spending.

Medicaid and school aid are supposed to be growing at rates set by separate statutory caps that are higher than 2 percent. Simple math dictates that accommodating higher growth in these two areas, which comprise 42 percent of the state operating fund budget, requires lower rates of growth or cuts in other areas. Under a cap tied to the annual increase in New York personal income, school aid is supposed to grow 4 percent next year and 5 percent in the following two years. Medicaid is expected to grow about 4 percent on average annually under a cap linked to the 10-year average of healthcare inflation.

Lower growth rates in these areas could be achieved, but doing so will be challenging. For two years the adopted budget has included school aid increases well above the cap, and in order to pay for the increases and hold overall state operating fund growth under 2 percent on a fiscal year basis, state officials have resorted to accounting tricks to push part of each school year’s funding into the first quarter of the next fiscal year. Last year a 5.3 percent school aid increase on a school year basis was financed by a 1.5 percent increase in fiscal year 2014 and a 6.0 percent increase in fiscal year 2015. The problem with relying to such an extent on the school aid “tail” is that growth promised in one budget year is pushed to the next, bumping up the fiscal pressure on each subsequent year of the financial plan. For example, while the Enacted Budget provides a 5.3 percent increase for school year 2015, aid will actually rise 6.1 percent in fiscal year 2015 and 7.5 percent in fiscal year 2016. To make cuts in school aid either these “tails,” or prior year commitments, will have to be broken or the new school aid agreed to in the current year budget will need to be below the school aid cap. Baseline reductions in school aid could be achieved, however, if resources were better targeted to the neediest districts and overly rich reimbursement formulas for functions such as transportation and capital construction were reformed.

In contrast to school aid, Medicaid spending by the Department of Health (DOH) has remained under its statutory cap, set at the rate of medical inflation, and has been a source of budget relief for other areas of state operations in recent years. In fiscal year 2014, for example, when the federal government reduced the reimbursement rates for institutional facilities for the developmentally disabled run by the Office for Persons with Developmental Disabilities, DOH was able to absorb $730 million through the creation of a “stabilization fund” for mental hygiene services within the amount of spending allowed under the cap. DOH is planning to distribute $8 billion over the next five years in federal funds from a waiver to the State’s Medicaid Plan. If the federal aid is spent on reforms that reduce costs, Medicaid spending projections could be lower. However, to some extent the effects of the waiver are already accounted for in the financial plan, which shows budget relief under the Medicaid cap ranging from $270 million in fiscal year 2015 to $688 million in fiscal year 2018. Although additional relief may be possible, it is unrealistic to budget for more at this time.

Other areas of the state budget, such as pension contributions and debt service, are difficult, if not impossible, to change in the short term. Savings from the significant pension reforms enacted two years ago will not generate substantial savings over the length of the financial plan because they only apply to new hires. Savings accumulate only through the gradual turnover of the workforce. Similarly, debt service largely funds prior capital obligations and cannot be reduced all that much in the short term. In addition, the adopted budget included $7.6 billion in new bond authorizations that will add to debt service costs.

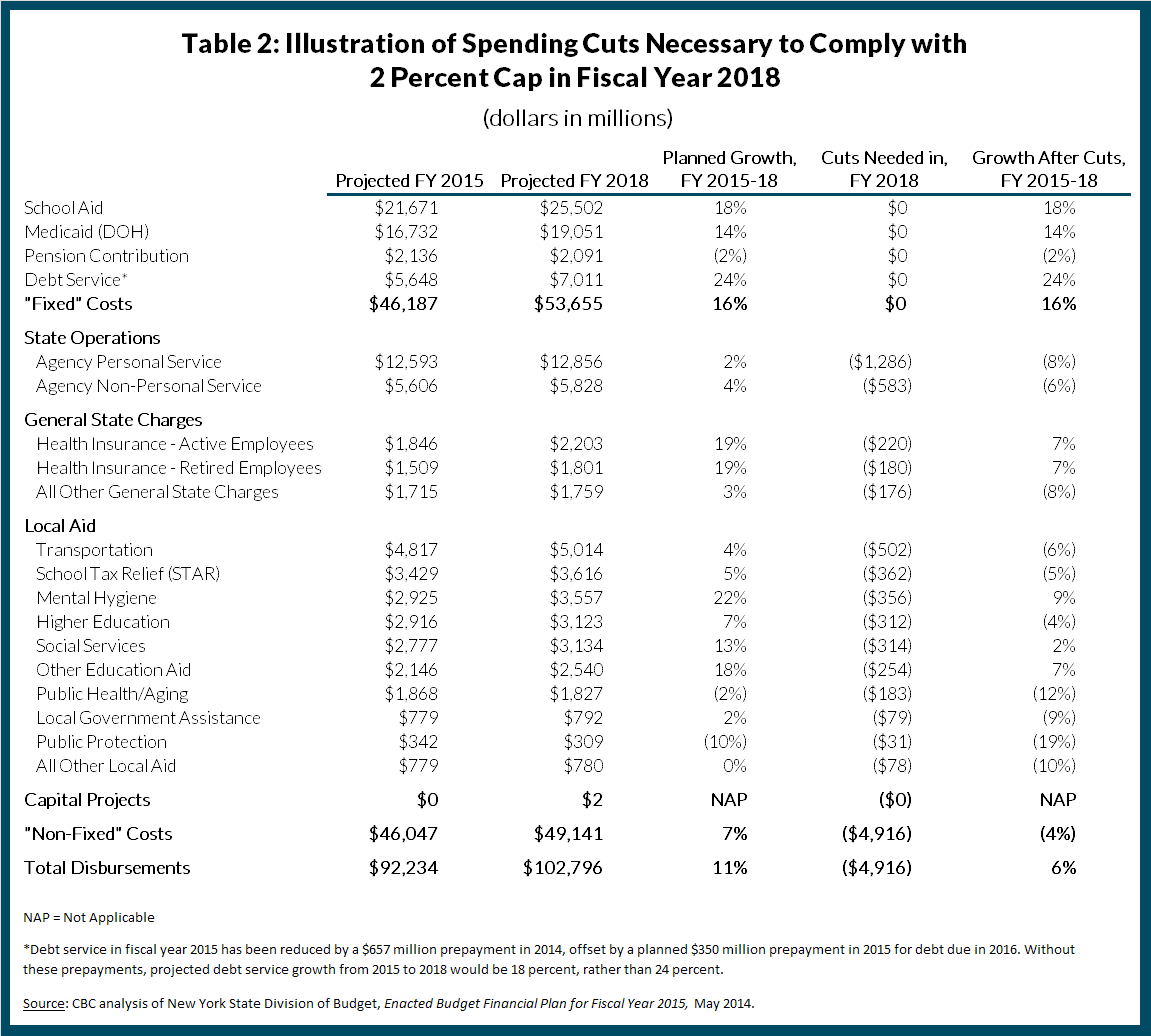

Together school aid, Medicaid, pension contributions, and debt service are projected to grow 16 percent from fiscal years 2015 to 2018. (See Table 2.) If no adjustments are made to projections in these more fixed parts of the budget, adhering to the 2 percent spending cap for state operating funds would require spending 4 percent less in fiscal year 2018 than is budgeted this year for all other categories of state spending. Assuming proportionate reductions, over the next three years agency personal service would need to be reduced by 8 percent, or $1.3 billion less than current projections, a difficult task even without likely wage increases in the next round of labor contracts. Reductions of this magnitude would cause year-to-year drops in most categories of local aid, including a drop of 6 percent over the next three years in transportation aid and a 12 percent drop in aid for public health/aging.

Until realistic plans are made to adhere to the 2 percent spending cap, there should be no illusions about spending a “surplus.” A more sensible approach to presenting the fiscal challenges that lie ahead is to return to a straightforward and transparent financial plan, one that shows the baseline budget gaps that result from the actions taken in this year’s budget.

By Elizabeth Lynam and Tammy Gamerman