Labor Costs in New York State – How to Save $1.2 Billion

Labor costs are one of the "big 3" categories of spending, along with school aid and Medicaid, that drive the size of the State budget. Yet Governor Paterson's Executive Budget included an unspecified plan for achieving savings from organized labor - a target of $250 million is included in the financial plan along with a menu of possible options for the labor unions to consider. In subsequent years the savings drops to $125 million in fiscal year 2011-12 and then to $0 in fiscal years 2012-13 and 2013-14.

Now that the Governor has decided he is not running for election this year he can be more aggressive with the State's public employee unions and begin to broadcast the fact that one of the pillars of any strategy to get New York's fiscal house in order must be a smaller, more effective and reasonably compensated government workforce.

The Problem: Unsustainable Trends

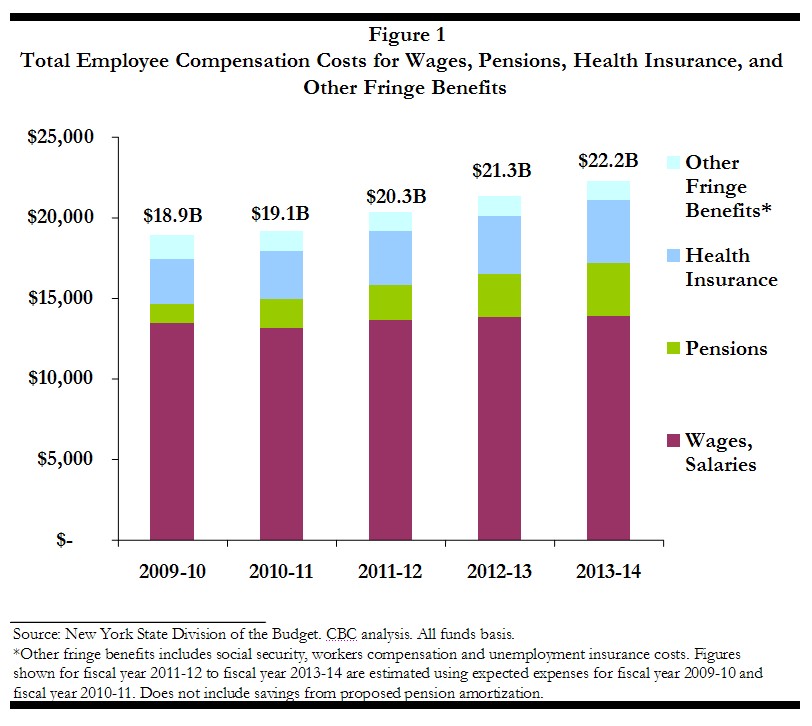

Employee compensation in fiscal year 2009-10 (the year that will end on March 31), including wages and salaries, health insurance, pensions and other fringe benefits is $18.9 billion. On a per employee basis this averages about $87,000 per year.[1] With rapid growth expected in pension and health insurance costs and no major changes to wages and salaries, in fiscal year 2013-14 total compensation will reach $22.2 billion, an increase of $3.3 billion, or 18 percent. These planned increases and a level number of employees translate into total average compensation costs of about $102,000 per employee by fiscal year 2013-14.[2]

Pension and health care costs are particularly fast growing. In fiscal year 2009-10 the cost of these two items consumed about 11 percent of general fund tax revenues; by 2013-14 the amount will grow to 16 percent. By fiscal year 2013-14 the fringe rate as a share of salary is projected to reach 60 percent. Health insurance costs are expected to grow by 40 percent over the financial plan period and pension costs by a whopping 184 percent. Pension costs reflect the phase-in of $45 billion in payments to compensate for assets lost last year from the stock market decline combined with benefit enrichments over the past decade. Changes in benefits for new employees, known as Tier V and enacted by the Legislature in December 2009, will not generate substantial savings until well into the future as new employees replace current ones. The new tier also does not cover uniformed services, which have the most costly pensions.

Pensions

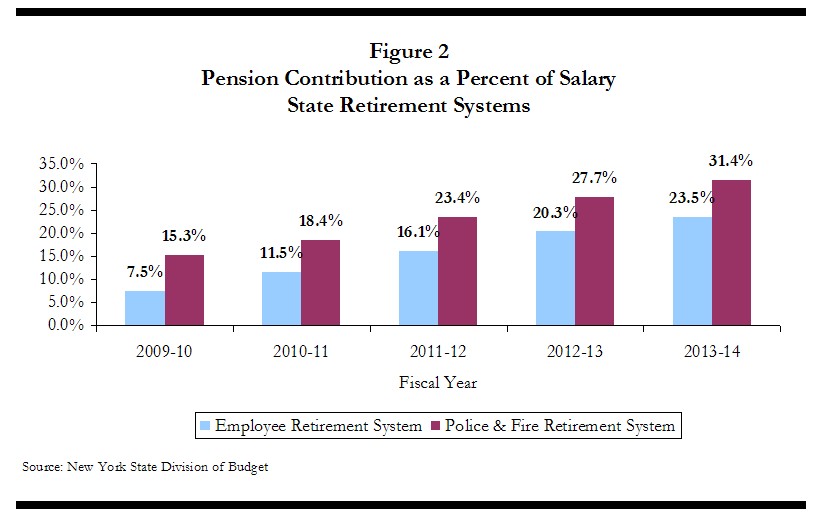

As a share of payroll costs, the required pension fund contributions are skyrocketing. In fiscal year 2013-14 for civilian state and local employees enrolled in the Employee Retirement Systems (ERS) the pension contribution to the pension system as a share of salary will triple, increasing from 7.5 percent in fiscal year 2009-10 to 23.5 percent in fiscal year 2013-14. (See Figure 2.) For uniformed employees with more generous retirement benefits in the Police and Fire Retirement System (PFRS) the required employer contribution in fiscal year 2013-14 will be the equivalent of nearly a third of an employee's annual salary.

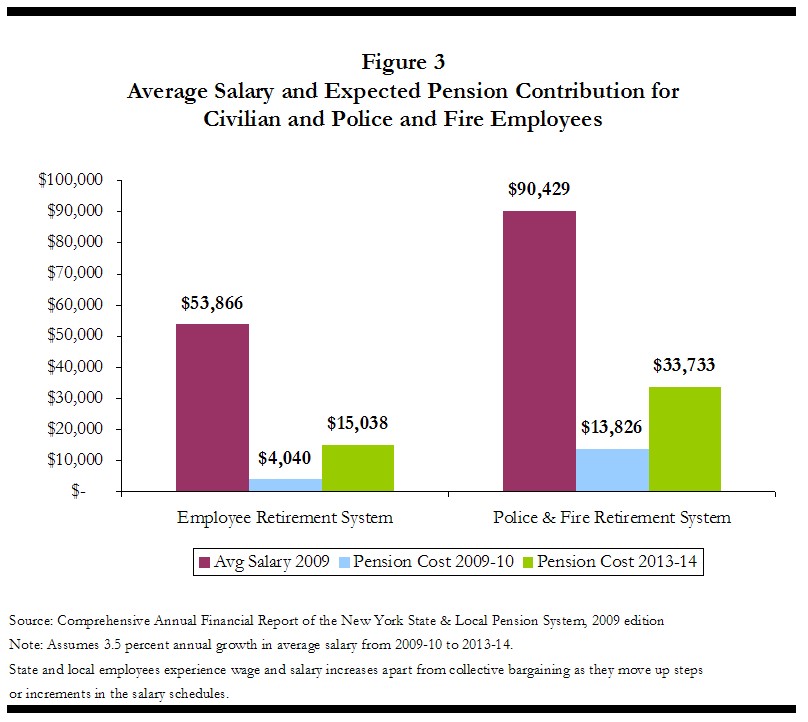

Salary alone (no benefits) for State civilian employees averaged $53,866 in fiscal year 2008-09; in comparison their uniformed counterparts received an average salary of $90,429. (See Figure 3.) The average amount the State is required to contribute to pension funds in fiscal year 2009-10 is $4,040 for the civilians and $13,836 for uniformed employees. By fiscal year 2013-14 these amounts are projected to grow to $15,038 for the civilian and $33,733 for the uniformed employee if current assumptions hold. If the pension funds experience further investment losses, then the amounts could be even higher.

Employees are required to contribute to their pensions. Newly hired Tier V members will be required to contribute 3 percent. Unlike most plans in the private sector the State's plans are defined benefit rather than defined contribution, meaning that employees are guaranteed a payment for life once they have vested and reached retirement age. The difference is significant. For example, assuming that State salaries grow about 3.5 percent annually a state employee beginning work today at an entry salary of $30,000 who works in state government for 30 years and retires at age 62, can look forward to an estimated three-year final average salary of $78,636.[3] The annual pension benefit would be 60 percent of that amount, or $47,182.[4] The amount needed to guarantee this payment annually for 20 years with an estimated 1.5 percent cost of living increase that is currently in place in State law from year 10 forward is $984,364.[5] Toward this nest egg the employee would have contributed an estimated $46,460.[6] An employee in the private sector with the same salary and a five percent return rate on investments would need to contribute $503,000 over his or her 30-year career to amass the same nest egg. At an eight percent return rate $315,000 would be required.

Health Insurance

Growth in health insurance costs is a national problem. New York purchases health insurance for its State employees, retirees, and participating local employers through the New York State Health Insurance Plan (NYSHIP). In recent years increases in premium costs have been averaging 5 to 6 percent, which is about the national norm. The financial plan uses a planning assumption of future growth of 8 to 9 percent per year.

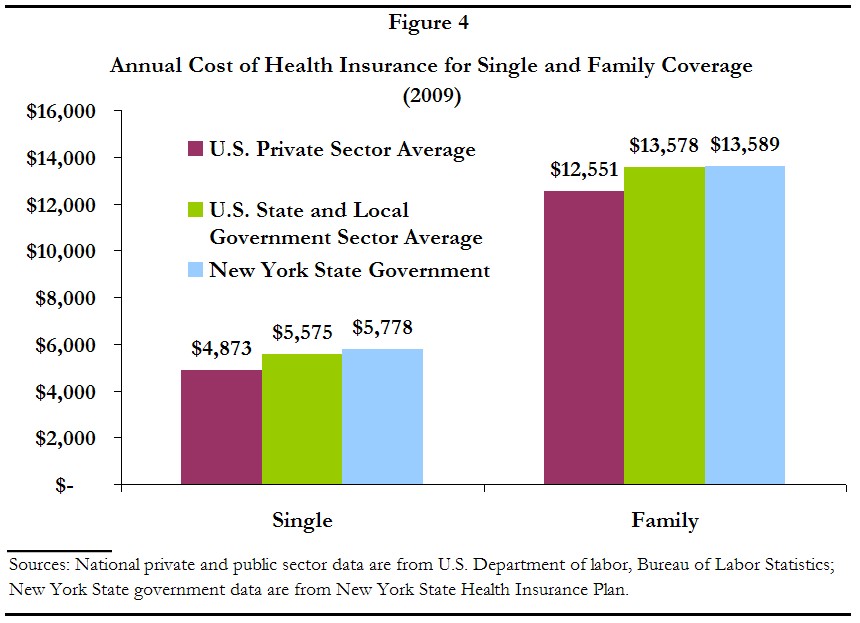

The basic cost of a health insurance policy in New York is about the same as for a public sector plan nationally. Single employee coverage is $5,575 annually in the nation and $5,778 in New York and family coverage is $13,578 nationally compared to $13,589 in New York. (See Figure 4.) In the private sector the average costs are $4,873 and $12,551 for single and family policies, respectively. Compared to national private sector norms New York's costs are 18.6 percent higher for a single policy and 8.3 percent higher for a family policy. Cost of living differences suggest that a higher premium in New York may be reasonable. However, estimates of cost differences that vary to such a large extent by policy type seem questionable; since family policies are closer in cost to national norms there may be room to improve the premium costs for single policies.

Premium sharing arrangements with current State employees are close to public sector norms, but greater contributions are typically required of private sector employees. Bureau of Labor Statistics data show that State and local public employers require employees to pay 10 percent of single policy premiums and 27 percent of family policy premiums. Among private sector employers nationally employees are required to pay 20 percent of single policy costs and 30 percent of family policy costs. The Federal Employee Health Program requires that 25 percent of the premium be paid for both single and family coverage. New York's current requirements are 10 percent for single policy holders and 25 percent for family policy holders.

For retirees, however, New York is significantly out of line. A recent comprehensive compensation survey of private employers shows that retirees under 65, so-called "early retirees" because they do not yet qualify for Medicare, on average contribute 51 percent of the cost of their medical coverage.[7] The same survey shows that even retirees that are 65 and over pay 48 percent of their medical coverage costs. On paper New York's current premium sharing arrangements are 10 percent for single policies and 25 percent for family policies. In practice premiums are even lower because when they retire employees can "buy down" the cost of future premiums by using unused sick days. Retirees are also reimbursed the cost of Medicare Part B premiums, which is $1,152 per year per retiree. Total expenses for Medicare Part B in fiscal year 2009-10 are $138.8 million.[8]

Minimal Recent Reductions in State Employment

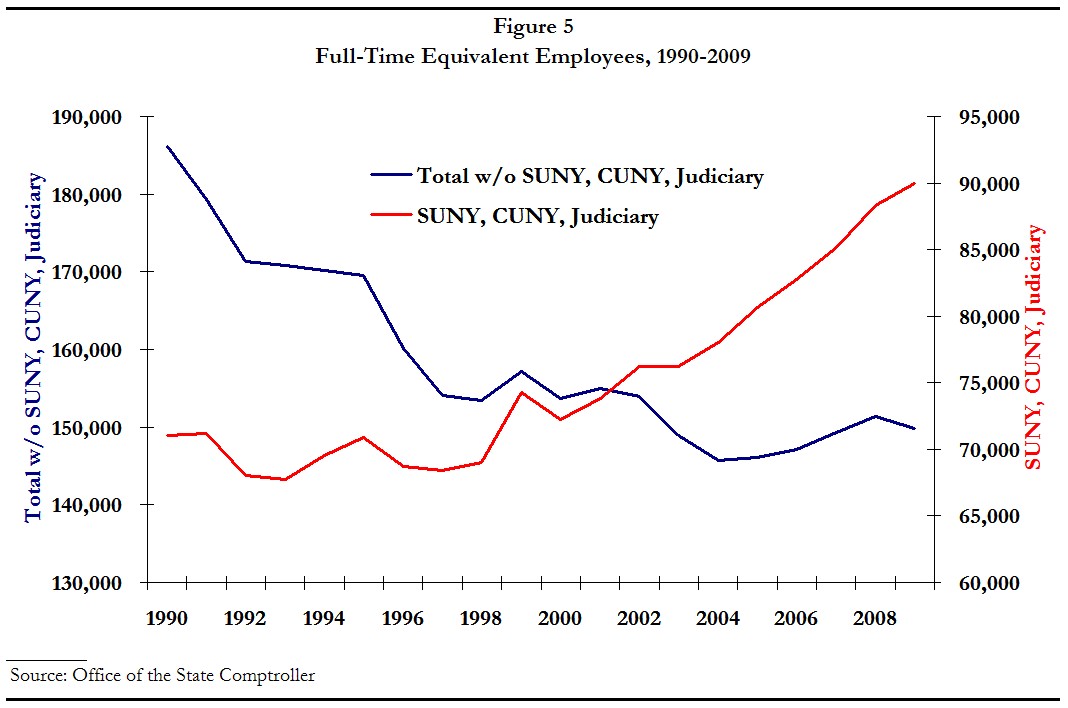

Increases in the cost of State operations are being driven by rising costs-per-employee not the addition of employees to deliver new programs and services. Since 1990, the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) employees in the Judiciary, State University of New York (SUNY), and City University of New York (CUNY) has grown by 19,000, while the rest of State government has shrunk by 36,000. (See Figure 5.) Employment levels in the Judiciary, SUNY, and CUNY are not under the control of the Executive branch and hence, not subject to gap-closing measures imposed on other state agencies by the Governor.

When the revenue forecast began to deteriorate in January 2008 the State employed 230,450 full-time equivalents. In January 2010 when the Executive Budget was released the FTE employment was 228,595, a net reduction of 1,856 or 0.8 percent. The Office of Mental Retardation and Development Disabilities, Office of Mental Health, Office of Children and Family Services, and the Department of Corrections have sustained cuts of over 4,000 FTEs. Over the same period the number of FTEs at SUNY and CUNY grew by over 2,900. The Department of Tax and Finance and the Department of Labor have also grown to meet staffing needs for new policy initiatives (to meet new tax compliance targets and federally-backed employment programs). (See Figure 6.)

he Division of Budget reports that at the end of fiscal year 2007-08 199,754 people were employed in full-time positions. By the end of fiscal year 2009-10, that number will be reduced by 3,379 positions to 196,375. For the coming fiscal year the Executive Budget proposes another reduction of 674. The small drop is anticipated despite the budget expectation that attrition across the agencies would reduce full-time positions by more than 16,000 in the coming year. If the Executive proposals are accepted, the total three-year reduction in full-time employment will be 4,053, or 2 percent.

The Solution: A More Comprehensive Approach than a $250 Million Plug

If every action the Governor proposed in the Executive Budget is accepted by the Legislature, the fiscal year 2013-14 budget gap will still be at least $12.4 billion. This size of a gap cannot be closed without more comprehensive adjustments to the State's employee compensation structure than a $250 million short-term gimmick, such as wage deferrals, can provide.

State employee contracts with the major unions are set to expire on March 31, 2011. In two days, on April 1, 2010, a 4 percent increase will go into effect. A wage freeze in which State employees forego that increase (as opposed to a deferral that will push costs into the future) would be a good start, but not at the expense of failing to take the other necessary actions discussed here. Greater recurring savings and more thoughtful approaches for the long run should be the first priority.

Changes to Fringe Benefits - Sharing More Downside Risk with Employees and Retirees

With the depressing impact of lower revenue streams New York must be realistic about how far above national norms its employee compensation can be. Although a typical point of comparison for New York's public sector compensation is other jurisdictions' state and local public sector compensation, if New York is to become more competitive in a difficult and uncertain economic climate, private sector norms should prevail. In the private sector a greater share of downside risk is borne by employees. The greatest downside risks are the rapidly mounting costs of health insurance and pensions for current and retired employees. The funding requirements associated with the pension system are doubling and tripling in three years time, health insurance costs are expected to grow by 40 percent, and the unfunded liability of providing retiree health care for State employees is estimated at $56.3 billion.[9]

Because New York has paid the annual bill for its retirement system reliably over time it is a relatively well funded system relative to other states. The answer is not to start a pension borrowing scheme as proposed in the Executive Budget. This pushes costs out to later years and jeopardizes the long run funding stability of the plans. The solution for the long run is to share risk in two ways.

First, more of health insurance premium costs should be shared with current and retired employees. For single policies the individual's share of the premium should increase from 10 to 20 percent. For families the premium sharing should increase from 25 to 30 percent from its current level of 25 percent.[10] For retirees the premium sharing should be increased to 50 percent for both single and family policy holders. In addition, the practice of allowing retirees to buy down the future costs of health care premiums by applying unused sick days should be discontinued and the highly unusual reimbursement for the cost of Medicare Part B premiums ended.

The estimated fiscal benefits associated with these changes are $581 million. (See Table 1.) As health insurance costs in the plan grow so would the savings.

Second, a defined contribution option should be added to the pension system for all State employees. The SUNY system already has one that could be used as a starting point for negotiations on how to structure the option. New hires could be given the option to enroll at the outset of their employment with incentives to join. Since the current matching rate in the defined benefit plans is expected to rise to 25 to 34 percent of salary depending on the pension system, a very substantial match could be affordable. An initial "seed" deposit from State funds could also be offered for less than a typical year's employer deposit. New employees who anticipate greater mobility in their careers might prefer a portable option to a fixed plan. Ultimately the State should move away from a system where its downside risk for contributions can range from 5 to 11 to 33 percent of salary while the employee's is fixed at 3 percent. If, for example 10 percent of the workforce could be enrolled in the new plan by fiscal year 2013-14 and they were matched at $5,000 per civilian employee and $10,000 per uniformed employee, then estimated savings for the State would be $194 million.[11]

Greater Reductions in State Employment - A Broader Examination Is Needed

Since the State's fiscal crisis began State employment has been reduced by just 1.6 percent, or 3,640 positions. In this coming year the Executive Budget proposes to reduce full-time positions even less, by just 0.03 percent, filling nearly 16,000 positions expected to be vacated through attrition to reach a total position count that is 674 less at the end of fiscal year 2010-11.

This plan is insufficient in the face of a future budget gap in year three that is likely to exceed $12.4 billion. The need to fill any position in State government in the coming year should be reexamined. The savings from not filling the 16,000 positions is estimated to reach $800 million.[12] Part of the negotiations with the public employee unions should include adding hours to the workweek in order to reduce needed staffing levels and overtime. The current workweek for the majority of the State workforce is 37.5 hours. Even if half the savings from not filling vacant positions were allocated to paying current employees for covering additional duties, $400 million still would be saved.

By Elizabeth Lynam and Tammy Pels

Footnotes

- The calculation divides total spending numbers for personal services shown in Figure 1 - $18.9 billion - by a headcount of 217,965 (196,375 full-timers plus 18,080 employees of the Judiciary and 3,510 employees of the Legislature).

- The calculation divides the fiscal year 2013-14 spending estimate shown in Figure 1 - $22.2 billion - by 217,965 employees.

- $75,947, $78,605, and $81,356 divided by three equals $78,636.

- After year 25 on Tier V the annual credit earned increases from 1.875 percent to 2 percent per year. Over 30 years this equals 60 percent of final average salary.

- Assumes amount is converted to an annuity with no further investment gains.

- Assumes employee contributes 3 percent per year for the entire length of employment.

- Survey data are from Towers Perrin, 2009 Health Care Cost Survey: 20th Annual Results Report, p. 8.

- New York State Division of Budget.

- New York State, Office of the State Comptroller, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, fiscal year 2009 edition.

- These changes would take New York's premium-sharing arrangements to the private sector norms nationally. In contrast, the City of New York has no premium-sharing with its employees or retirees and CBC has advocated for the City of New York to change its policies to at least reflect public sector norms

- The 2009 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report of the New York State pension system shows that there are 187,219 State members of the civilian Employee Retirement System and 5,700 State members of the Police and Fire Retirement System. Pension contributions in fiscal year 2013-14 are expected to be $14,671 for ERS and $32,909 for PFRS (See Figure 3). If $5,000 were deposited for 18,722 employees, or ten percent, of the ERS membership and $10,000 for 570, or 10 percent, of PFRS membership instead of the current contribution amounts, $181 million would be saved for civilians and $13 million for uniformed employees. This calculation assumes level membership.

- This calculation assumes an average starting salary of $35,000 and benefit costs of $15,000 for all 16,000 positions.