Mind the Gap

Funding Repair and Maintenance of New York City Infrastructure

New York City's extensive public infrastructure creates an important and expensive responsibility on the part of public officials to repair, maintain and enhance these assets. Generally, regular maintenance is funded in the City's operating budget, while repairs and improvements are funded in the capital budget. With the fiscal year 2011 operating budget recently approved, and the $46 billion, five-year capital plan up for review in the coming months, it is worth asking how well current budgets provide for repair and maintenance of public infrastructure.

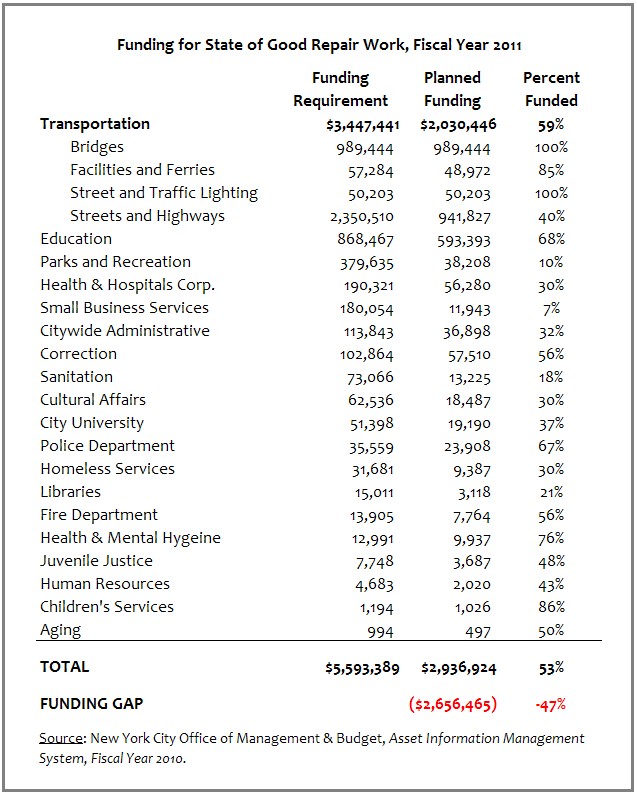

The answer is disappointing. Past neglect has created a need for nearly $5.6 billion in repair of existing facilities in order to bring them to satisfactory condition, defined by engineers as a "state of good repair." Yet the City's capital budget allocates only about half (53 percent) of what is needed, with the gap especially large for streets (40 percent funded), hospitals (30 percent funded) and parks (10 percent funded).

With respect to maintenance, current policies may lead to further deterioration and major repair needs. Across all facilities, only 70 percent of maintenance needs are funded in the operating budget, with cultural institutions, parks, libraries and higher education experiencing larger than average gaps in provision of adequate maintenance.

State of Good Repair

Achieving a state of good repair has been a central aim of the City's capital agenda for the past two decades. It is a goal that Mayor Michael Bloomberg explicitly endorsed for major infrastructure, i.e. transportation and water and sewer systems, in the PLANYC agenda.

The City Charter requires that the City report yearly on the spending required to reach a state of good repair in the Asset Information Management System (AIMS) report. The report has two parts. In the first, one quarter of the assets are surveyed on a rolling basis to assess their structural integrity and functionality, with spending requirements to remedy shortcomings identified. In the second part, agencies report how much of the necessary spending will be undertaken from both capital and expense budgets.

The AIMS report is far from comprehensive. The City Charter exempts assets with a replacement value of less than $10 million and a useful life of less than 1- years from AIMS, thereby omitting many assets from reporting requirements. It also excludes many assets that do not easily lend themselves to visual inspections by field engineers, such as piers and bulkheads. In addition, some important large assets, such as the East River Bridges and the water and sewer system, are not included (but are surveyed in other reports). Nevertheless, even with these limitations, AIMS provides a useful window into the City's management of its assets and the magnitude of spending necessary to properly maintain them.

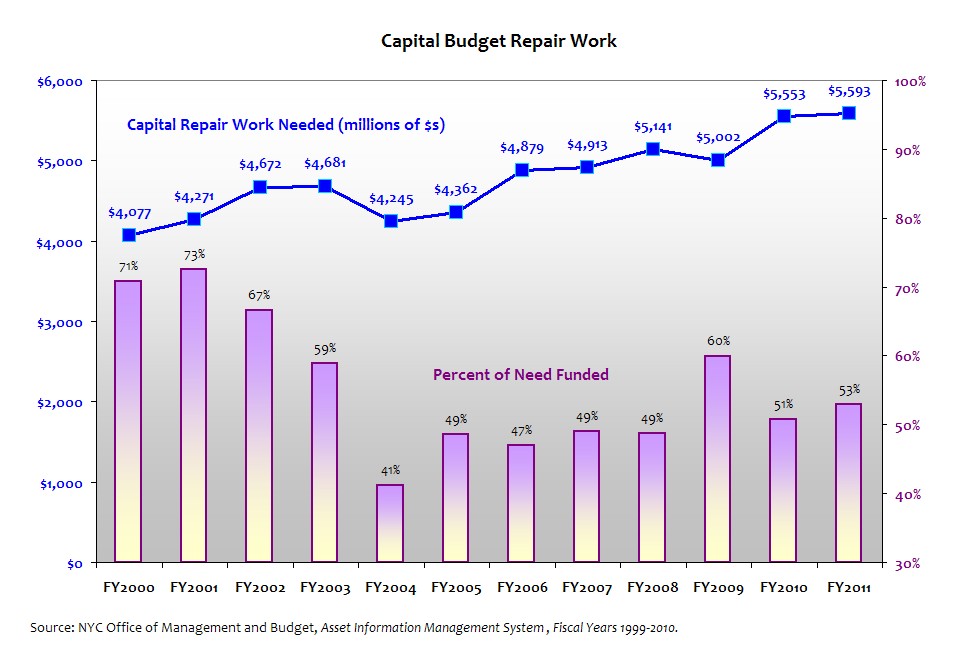

Review of AIMS reports since 2002 shows that the City has not made substantial progress in achieving state of good repair, and in fact, it may be falling further behind. The most recent report, detailing funding for projected needs for fiscal year 2011, was released last week. It indicates that $5.6 billion of capital work is needed to bring the assets surveyed to a state of good repair. To put this in perspective, this amount is 16.5 percent of the net value of all City-owned assets and is equal to approximately 50 percent of the City's capital budget in this fiscal year.

The amount required has increased sharply from fiscal year 2000, when needed capital repairs totaled $4.1 billion. While the estimated cost of repairs has increased by 36 percent since 2000, the funding devoted to addressing these requirements has decreased. In fiscal year 2011, funding for AIMS capital work will be $2.9 billion – 53 percent of what is required. Reluctance to fund AIMS requirements fully has resulted in a funding gap that has grown from 29 percent to 47 percent over the decade.

Most of the spending requirements for state of good repair cited in AIMS are for transportation assets. Within transportation, most of the need is for streets and highways; however, of the $2.35 billion required, only 40 percent will be funded. On the other hand, the City plans to fully fund almost $1 billion in state of good repair needs for bridges. Other agencies with high spending requirements include education ($868 million), parks and recreation ($380 million), and the Health and Hospitals Corporation ($190 million), but the percent of required work that will be undertaken varies widely: 68 percent for education, 10 percent for parks, and 30 percent for hospitals, respectively.

Routine Maintenance

The capital repair backlog has grown because the City is not adequately fulfilling its regular maintenance responsibilities, which are essential for keeping assets from falling into disrepair. These responsibilities include everything from periodic tune-ups and small repairs on equipment to replacing doors. Because this maintenance is funded from the expense budget, it competes with agency programs for funding, and is often a low-priority item; however, shirking these responsibilities can add costs down the road, as minor repairs may turn into major projects when neglected for too long. These major projects, in turn, become the state of good repair work that is eligible for funding through the capital budget; therefore, smaller investments in the expense budget on maintenance can prevent the need for capital spending later on.

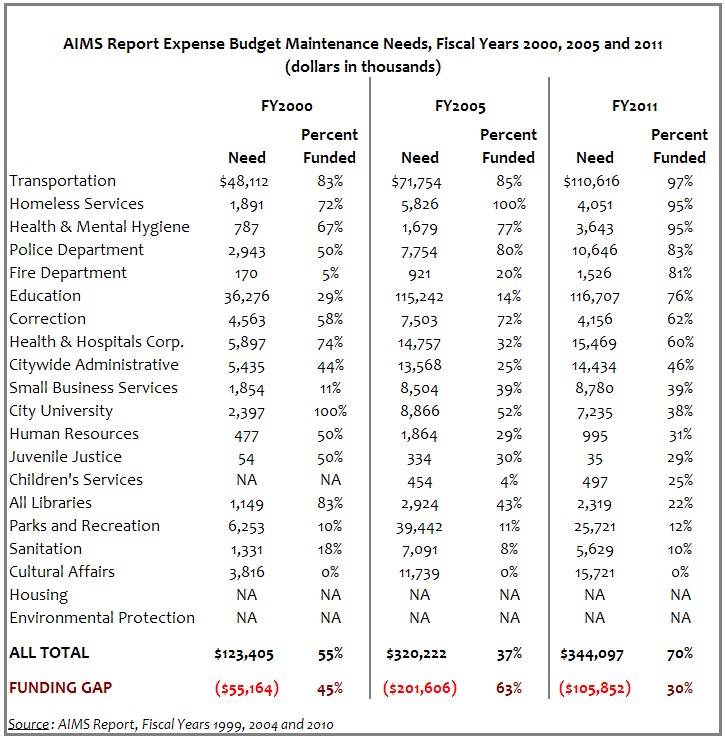

For fiscal year 2011, expense budget maintenance needs were estimated to be almost $350 million - almost triple the amount recorded in fiscal year 2000. Funding for maintenance out of the expense budget has grown over time, from $68.2 million to $161.6 million in fiscal year 2010; nevertheless, it has not grown fast enough to keep up with maintenance requirements. On average, only 46 percent of citywide maintenance needs have been funded since fiscal year 2000.

For the coming year, the AIMS report shows a large increase in overall maintenance funding, from $161 million to $243 million; however, this is mostly attributable to changes in reporting at the Department of Education. Even with this increase, there will still be a 30 percent gap between need and funding. Furthermore, funding among agencies varies widely. While the Department of Transportation will fund 97 percent of its reported need, the Department of Parks and Recreation will fund only 12 percent. The median level of funding for all agencies in fiscal year 2011 is 43 percent.

Rethinking Capital Management

In its 2007 report on capital budgeting, CBC recommended changes to the AIMS report, including expanding its scope and tying it directly to the capital plan. The City has initiated a review of AIMS focused on improving assessment methodologies, expanding the number of agencies included and providing more information to agencies to help them prioritize state of good repair.

These are important steps that will improve capital management, and should serve as a springboard for two additional reforms. First, the City should make full funding of maintenance requirements an explicit priority. Keeping up with routine maintenance work is necessary to prevent more costly capital repairs: it is more efficient to fix a leak in the roof today than to have to replace the entire roof down the road. While this requires resources from the operating budget, AIMS recommendations constitute less than one percent of the operating budgets of many agencies and no more than 10 percent of any agency budget other than transportation.

Second, the City should use the AIMS condition assessments as the starting point for developing the next ten-year capital plan, due this fall. More specifically, it should develop a strategy for upgrading all assets to a state of good repair. If $1.2 billion out of the capital program annually had been devoted to state of good repair instead of other projects between the boom years of 2006 and 2009, the need identified in the AIMS report for capital repair work would have been eradicated.

This does not mean that the City should be on the hook for fixing all infrastructure within the next ten-year period. Rather, it should consider a reasonable time-horizon for upgrading each class of assets and identify specific steps in the capital plan to make progress against those goals. Funding for state of good repair projects should be prioritized over expansion projects.