MTA’s New Capital Plan Not on Track with Need for Better Service

At its latest meeting, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) Board approved a revised capital plan that adds $2.8 billion in investments to bring the current five-year plan total to $29.5 billion.1 The amended plan follows months of criticism in the press of the declining performance of the subways and commuter railroads. But the new money and other changes to the capital plan are not wholly aligned with what is needed to get the trains running on time.

Prior to the May 24 MTA Board meeting Governor Andrew Cuomo and MTA leadership each released separate proposals to improve performance, but neither required substantial changes in the capital plan. The agency’s plan consisted of six points relating primarily to operational improvements to the subways; only the proposal to expedite the delivery of 300 new subway cars was financed in the capital program, and that funding that was already available.2 The governor called for changes in the management of Penn Station and announced a competition for innovations to speed implementation of already-planned improvements to subway signal systems, replacement and maintenance of subway cars, and installation of systemwide cellular and Wi-Fi connectivity.3 The capital requirements of any such innovations are unknown and will not be identified until the conclusion of this competition at a yet-to-be-specified date. Instead of linking to these ideas and to other long-standing investments needed to reverse declining performance—the first among equals being the modernization of the subway’s antiquated signal system—the capital plan amendment increases resources for lower-priority expansion projects.

The Amended Capital Plan Underfunds Priority Needs

Since 1982 the MTA has had a series of five-year capital plans intended to bring the region’s transit system to a state of good repair, maintain this state of good repair, and enhance and expand operations. These five-year plans identify specific capital projects to be funded, the year in which they are to be started, and their estimated costs.4 The current capital plan, covering the 2015 to 2019 period, was first proposed in September 2014. The Capital Program Review Board (CPRB)—a State oversight body that approves the capital plan for the subways, buses, and commuter railroads—rejected the plan without prejudice to any particular project.5 The MTA retooled the plan, addressing the governor’s concerns that it was “bloated”, by cutting nearly $2.6 billion.6 The CPRB approved this revised plan in May 2016, more than 16 months after the plan period was scheduled to begin.7

Capital plans are amended periodically to reflect the addition or elimination of specific projects, changes in cost estimates, and changes in anticipated project start dates. If amendments alter the total amount to be spent in the five-year period, they must be approved by the CPRB. The comprehensive amendment presented in May 2017 increased the size of the plan subject to CPRB review more than 10 percent above the originally-approved $26.6 billion.8 Most of the net increase came from increased commitments to network expansions, including the addition of nearly $2 billion for the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) Expansion Project and $700 million for Phase II of the Second Avenue Subway.

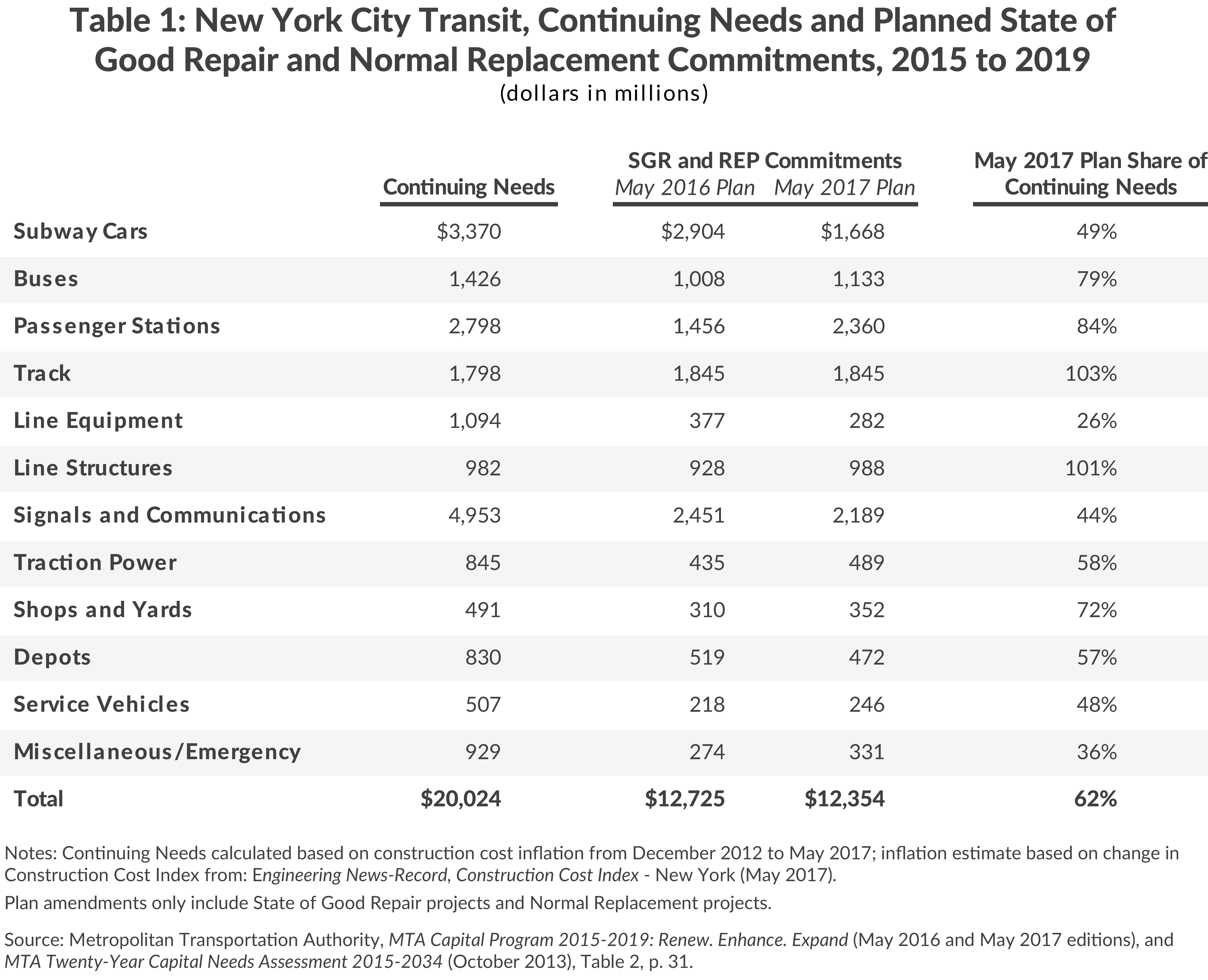

Despite the 10 percent increase in the size of the plan, the agency still intends to invest less than is required to keep the system in state of good repair and to enable current capacity to be used effectively. According to the MTA’s Twenty-Year Needs Assessment, used to guide the 2015-2019 capital plan, New York City Transit required $16.1 billion in Continuing Needs in nominal 2012 dollars, a total that includes nearly $4 billion for signals and communications systems, $2.7 billion for new subway cars, and $2.3 billion in passenger station projects.9 In 2017 dollars, the size of that need is more than $20 billion.10

Yet the recent amendment reduced total state of good repair and normal replacement commitments from $12.7 billion to less than $12.4 billion, decreasing sums dedicated to signals and communications systems, subways cars, and line equipment. (See Table 1.) Of 12 categories of assets, only track and line structures will receive sufficient funding to keep pace with continuing needs identified by the needs assessment.

Though the agency’s six-point plan is designed to address the increase in delays caused by signal malfunctions, rolling stock breakdowns, and power failures, all three categories will receive less than 60 percent of their continuing capital needs during the 2015-2019 period. Instead of accelerating the signal modernization program, which can allow trains to run closer together safely and increase the system’s reliability, the MTA will maintain the current pace of work.11 This despite the share of New York City Transit capital funding for signal modernization falling from 20 percent in the 2005-2009 and 17 percent in the 2010-2014 plan to to 14 percent in the 2015-2019 plan.12

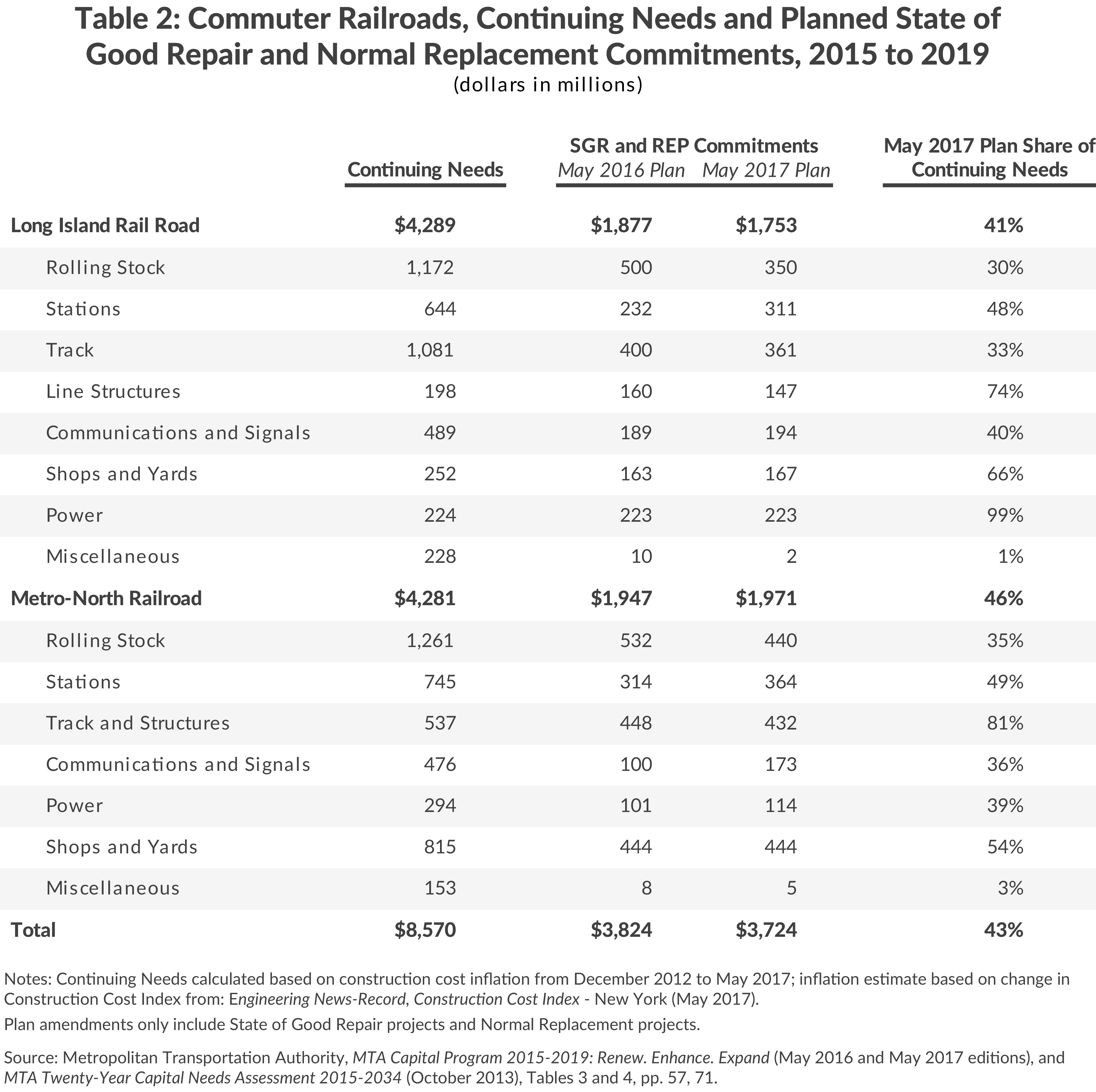

At Metro-North Railroad (MNR) less than two-fifths of continuing needs are funded for rolling stock, communications and signals, and power; at LIRR less than one-third of continuing needs are funded for rolling stock and track, and only 40 percent of needs are funded for communications and signals. (See Table 2.)

Added Money Goes to Expansions that Could be Deferred

Despite significant underinvestment in maintaining existing infrastructure the May amendment includes $2.7 billion in new capital commitments for two system expansions. The largest of the two, nearly $2 billion, will fund the Long Island Rail Road Expansion Project to build a third track for the 9.8-mile stretch of the railroad’s Main Line between Floral Park and Hicksville. The third track is intended to improve service reliability and flexibility as well as meet long-term demand growth.13 The Governor announced this project in January of last year , but it was not included in the 2015-2019 capital plan approved in May 2016.14

Accelerating this project’s timetable is arguably not the MTA’s best use of limited resources. The expansion is expected to be completed in 2021. It will ease congestion on a busy rail corridor and allow for more reverse commutation during peak periods; however, benefits from increased capacity to Manhattan is constrained and contingent on the completion of East Side Access—now delayed until the end of 2023.

The May 2017 Amendment also adds $700 million in commitments for Phase II of the Second Avenue Subway, extending it from 96th Street to 125th Street. The MTA initially considered delaying Phase II after the CPRB vetoed the September 2014 capital plan proposal citing a lack of time and capacity to implement the project during the five-year period.15 However, amid pressure from elected officials, the MTA promised to continue Phase II and assumed that the Federal Transit Administration’s (FTA) New Starts program would fund necessary commitments.16 The recent plan addition supports a local match.17

Prioritizing Phase II of the Second Avenue Subway over state of good repair work in the system is not prudent because federal funding may not materialize. New Starts is a competitive program with a finite amount of funding; the Phase II project must compete for funds, including against the new Hudson River tunnel which is an even higher priority for the region’s transportation network. Additionally, it is unclear if New Starts will be continued at its current levels; the Trump administration has zeroed out the program in its budget outline.18

Conclusion

Despite increasing the 2015-2019 capital plan more than 10 percent, the added investments do not address the causes of service deterioration head on. Instead of an all-hands-on-deck approach to improve transit service and reliability, the amendment adds funding for highly visible and popular expansion and enhancement projects. It is noteworthy that board members seemed surprised at the amendment’s submission. In voting against the amendment, one board member voiced his worry that the proposal had not been subjected to the kind of rigorous, public discussion it warranted. An increase in capital spending for projects in this amendment limits the MTA’s capabilities to address difficulties the riding public confronts on a regular basis.19 Though the MTA is halfway through the 2015-2019 capital planning period, future amendments can still reprioritize funds for more appropriate state of good repair work and for the modernization of the subway’s aging signal system. Going forward the board should require more transparency of changes to the capital program and emphasize what the agency can accomplish if capital funds are spent on state of good repair projects, existing system improvements, or both.

Soon the agency will embark on the first step of the 2020-2024 capital planning period. The 20-year needs assessment that will guide the next capital plan is scheduled to be released before the end of next year. Board members and the public must remain engaged in the MTA’s capital planning process to ensure the region does not squander another opportunity to reinvest.

Footnotes

- Metropolitan Transportation Authority, MTA Capital Program 2015-2019: Renew. Enhance. Expand. (as proposed to the MTA Board May 2017), http://web.mta.info/capital/.

- Metropolitan Transportation Authority, “MTA Announces 6-Point Plan to Restructure Management of the MTA, Improve System Reliability and Service” (press release, May 15, 2017), www.mta.info/news/2017/05/15/mta-announces-6-point-plan-restructure-management-mta-improve-system-reliability-and.

- New York State Office of the Governor, “Governor Cuomo Challenges MTA to Modernize Subway System With Launch of “The MTA Genius Transit Challenge” (press release, May 23, 2017), www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-challenges-mta-modernize-subway-system-launch-mta-genius-transit-challenge.

- Selma Mustovic and Charles Brecher, Working in the Dark: Implementation of the MTA’s Capital Plan (Citizens Budget Commission, October 2009), p. 1, https://cbcny.org/research/working-dark-0.

- The CPRB is composed of four voting members who represent the governor, State Senate, State Assembly, and New York City mayor. See: Joan McDonald, Letter to Thomas F. Prendergast, “Capital Program Veto Letter,” (October 2, 2014; accessed October 20, 2014), www.scribd.com/doc/241839626/Capital-Program-Veto-Letter.

- The Governor questioned the MTA’s initial proposal calling it a “bloated” first request sent to the Governor as part of the “dance” in coming up with a final, more realistic budget. See: Kate Hinds, “New York Governor Says MTA’s $15 Billion Budget Gap Is Part of the ‘Dance’,” WNYC, Transportation Nation (October 7, 2014), www.wnyc.org/story/cuomos-mta-dance/.

- Metropolitan Transportation Authority, MTA Capital Program 2015-2019: Renew. Enhance. Expand. (as approved by the CPRB May 2016), http://web.mta.info/capital/pdf/MTA_15-19_Capital_Plan_Board_WEB_Approved_v2.pdf.

- The MTA board approved a smaller amendment in February, which added three station investment projects totaling $399 million. These changes are funded by changes in other work and funds from prior capital plans and brought the CPRB plan’s total to $26.7 billion. See: Metropolitan Transportation Authority, Board Materials, Capital Plan Amendment (February 23, 2017), http://web.mta.info/mta/news/books/.

- Continuing needs include investments necessary to continue restoring the system to a state of good repair and replacing assets that reach the end of their useful lives before they fall into disrepair. Continuing needs exclude investments in new routes and extensions. See: Metropolitan Transportation Authority, Twenty-Year Capital Needs Assessment, 2015-2034 (October 2013), pp. 28-30, http://web.mta.info/mta/capital/pdf/TYN2015-2034.pdf.

- This is calculated based on construction cost inflation of 4.4 percent from 2012 to 2017; inflation estimate based on change in Construction Cost Index from: Engineering News-Record, Construction Cost Index - New York (accessed June 8, 2017), www.enr.com/economics/historical_indices/NewYork.

- Regional Plan Association, Moving Forward: Accelerating the Transition to Communications-Based Train Control for New York City’s Subways (May 2014), http://library.rpa.org/pdf/RPA-Moving-Forward.pdf.

- Ronnie Lowenstein, Director, City of New York Independent Budget Office, letter to the Honorable Gale Brewer, Manhattan Borough President, (June 11, 2017), www.ibo.nyc.ny.us/iboreports/mta-service-delays-disruptions-letter-2017.pdf.

- The project will also eliminate seven existing grade crossings; modify signal systems, substations, culverts, interlockings, crossovers, sidings, track bed, power systems, communications and signals; relocate utilities; and improve passenger stations along the route. See: Metropolitan Transportation Authority, MTA Capital Program 2015-2019: Renew. Enhance. Expand. (as proposed to the MTA Board May 2017), p. 93, http://web.mta.info/capital/.

- The governor announced that the MTA would move forward with the project’s environmental impact statement, a necessary step before it could be included in the 2015-2019 capital plan. See: Metropolitan Transportation Authority, Long Island Rail Road Expansion Project from Floral Park to Hicksville Final Environmental Impact Statement (April 2017), www.amodernli.com/environmental-study/#feis.

- Kate Hinds, Transportation Nation, WNYC “New MTA Capital Plan Slashes Funding for Second Avenue Subway” (October 28, 2015), www.wnyc.org/story/mtas-capital-steeplechase-clears-latest-hurdle/.

- Ross Barkan, “Members of Congress Fume After MTA Slashes Second Avenue Subway Funding,” Observer (October 20, 2015), http://observer.com/2015/10/members-of-congress-fume-after-mta-slashes-second-avenue-subway-funding/.

- New Starts are discretionary capital improvement grants that require a local funding commitment. Moreover, the Federal Transit Administration, the grant awarding agency, highly rates projects with substantial local commitments. See: Kate Low and Sandra Rosenbloom, The Federal New Starts Program: What Do New Regulations Mean for Metropolitan Areas? (Urban Institute, March 20145), www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/22481/413084-The-Federal-New-Starts-Program-What-Do-New-Regulations-Mean-for-Metropolitan-Areas-.PDF.

- Emma Fitzsimmons, “Trump Budget Leaves New York-Area Transit Projects Up in the Air,” New York Times (April 3, 2017), www.nytimes.com/2017/04/03/nyregion/trump-budget-leaves-new-york-area-transit-projects-up-in-the-air.html.

- Comments from David Jones, Boardmember, Metropolitan Transportation Authority, before Metropolitan Transportation Authority Board Meeting (May 24, 2017), https://youtu.be/HbaV_zIXlGM?list=PLZHkn788ZQJO31CGz8nJVYE5jwaHgqWfg&t=6660.