Needed Mandate Relief on the Way?

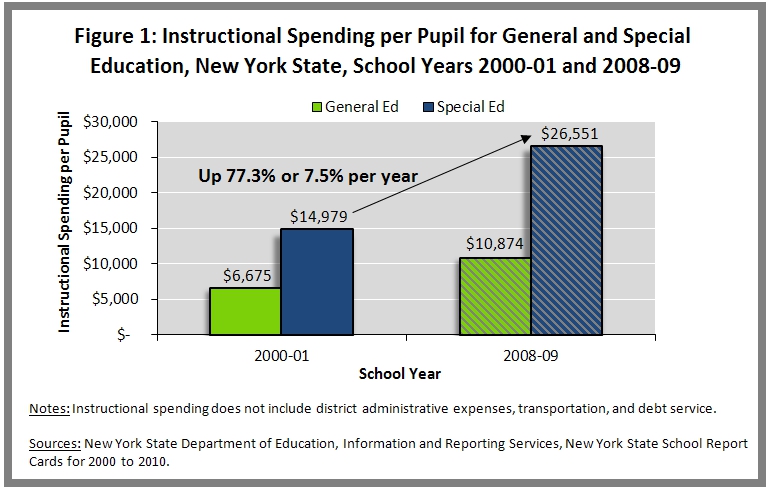

New York State imposes more than 200 special education mandates above and beyond those required by federal law.[1] Some were put in place to protect due process or guarantee timely services, while others limit class sizes and caseloads. All translate into higher costs and help fuel rapid spending growth. In 2008-09, the most recent school year for which data are available, the average cost of instruction per general education student in New York State was $10,874; for special education students the cost was 2.4 times greater, at $26,551. Instructional spending for special education has increased over the past decade at an average annual rate of 7.5 percent, growth that is 20 percent faster than for general education. School districts may find some relief if reforms moving through the New York State Department of Education are approved. The changes would bring New York’s special education procedures more in line with federal requirements.

A set of proposals was released by the State Education Department early in June with the expectation that it would go before the Regents in September after a period of public comment. In September action on the proposals was put off until November. There is no shortage of adversaries. Public employee unions, professional associations, and special education advocacy groups around the State have mounted considerable opposition to the changes. Jobs are at stake to be sure—New York is running one of the most intensively staffed special education systems in the nation. Across all occupational special education titles New York’s school districts employ 1 staff person for every 5.5 students compared to the U.S. average of 10.1.

The Regents should resist the temptation to weaken the proposals or postpone them once again. The original list of changes under consideration should be on the agenda for the November meeting and approved. Then the forum will shift to the legislature, which can do its part by passing the necessary changes to State law. With special education costs growing exponentially and revenue stream limited by the new property tax cap, school district leaders need greater flexibility to manage services.

What is Special Education and how much does it cost?

Special education began as a federal mandate in 1975. Current federal law requires public schools to offer students aged 3 to 21 with special needs an individually tailored program that enables them to participate with and learn the same material as other students to the maximum extent feasible. In New York there are 13 defined disabilities that can trigger special education services, including autism, learning disabilities as well as visual, hearing, orthopedic, and other health impairments.[2] Services range from “related” services - speech therapy, occupational therapy, physical therapy, and/or psychological counseling - in individual or group settings, to special school placements and one-on-one schooling in the student’s home.

Each student that is “classified” as needing special education is given an Individualized Education Program, or IEP, which spells out educational goals and objectives, and the accommodations and interventions necessary to achieve them. This document is prepared by an interdisciplinary team known as a Committee on Special Education (CSE) for school-age children or a Committee of Preschool Education (CPSE) for preschool children; the Committees include the student’s teachers, parents/guardians, and a variety of other mandatory members. The IEP confers on the classified student a federal right to these exact services. Any variation or change in services provided by the school district must be made on the IEP.

The cost of special education is substantial. In school year 2008-09 instructional spending per pupil for general education (an amount that includes a pro rata cost for building level administration but not district level expenses, such as debt service or transportation) was $10,874. For students in special education the instructional costs were 2.4 times greater, $26,551 per pupil (See Figure 1.) Although the costs for general education instruction have been rising, the costs for special education have been rising even more rapidly. From school year 2000-01 to 2008-09 per pupil instructional expenditures in general education increased an annual average of 6.3 percent; in special education over the same period per pupil instructional expenditures increased an annual average of 7.5 percent.

These growth rates are unsustainable. The federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) provided a temporary boost in school aid and in particular provided funds specifically for special education to help states adjust to the economic downturn, but these funds have run out. State aid for school year 2011-12 was cut $1.3 billion from the previous year’s level and the Governor’s planned growth in school aid is the historical average growth of personal income or about four percent. Moreover, local revenue from the property tax, which provides more than 50 percent of local school district resources outside of New York City, is now constrained by the state-wide property tax cap to growth of 2 percent. It will be nearly impossible to curb school spending to the extent required by these realities without addressing the significant and rapidly increasing expenditures for special education.

Although many factors influence school district staffing decisions, New York’s additions to federal mandates add personnel and, therefore, cost. For example, New York requires that students receiving only related services for a few hours a week or more be classified and given IEPs. Federal law does not require this and other states provide these students with related services without prescribing it on an IEP. New York also requires a psychological exam as part of the process for classification and placement, and that a psychologist be on the committee that decides about special education services. Caseloads, frequencies of service, and class size are also regulated.

These State mandates contribute to a system of special education that is one of the most intensively staffed in the nation. Across almost all categories New York ranks in the top ten states for student-to-special-education-personnel ratios. In three categories—psychologists, occupational therapists, and physical therapists—New York ranks number one. (See Table 1.) For teachers and speech and language pathologists New York ranks number two. For social workers New York ranks third. Overall New York employs nearly two times as many professionals per special education pupil than the national norm—the student-to-staff ratio in New York is 5.5 compared to the U.S. average of 10.1.

Changes under Consideration by the Board of Regents

The Board of Regents has been making progress in reducing special education mandates. Mandate relief proposals were approved at the November 2010[3] and March 2011[4] Board of Regents meetings. A third round of relief is expected to be on the agenda for the Regents November 2011 meeting. The proposals under consideration have been the subject of a public comment period that began in June. These should go to the Regents unchanged by pressure from special interest groups. The agenda for the meeting should contain the following special education mandate relief items:

- The membership of the CSE be conformed to the federal IEP team membership; the state-imposed additional requirement to include a school psychologist, a parent of a student with a disability, and a physician if requested by the school or parent 72 hours before the meeting, would be repealed. If State law is changed to conform, the law that applies to New York City would also be changed.[5] In addition to Regents approval, this alteration in CSE membership requires statutory change.[6]

- The State Education Department’s view is that state regulations allow parents and school districts the discretion to invite other individuals who have knowledge or special expertise regarding the student to CSE meetings. If New York aligns with the federal IEP team membership, the parent and/or district could, in light of the needs of a particular student, continue to include as members, the school psychologist, another parent or a physician. In addition, the school psychologist could be a regular member, serving as one of the other federally mandated participants.

- The CPSE membership would be aligned with the federal IEP team, by repealing the requirement that CPSE include an additional parent member. The municipality representative would continue until such time that the county no longer has a role in the provision or payment of special education to preschool students, and then be eliminated. In addition, the requirement that the parent select the preschool evaluator would be replaced with the requirement that the school district consult with the parent regarding the selection of an evaluator. All school districts would be approved preschool evaluators. These changes must be made in State law after Regents approval.[7] An additional mandate relief is to align the preschool initial evaluation timeline to the evaluation timeline for school-age students (60 calendar days) a change that can be made in regulation.

- The federal standard for initial evaluations would be adopted by repealing the requirement in State law that each evaluation of a student suspected of having a disability include a physical examination, psychological evaluation, social history, observation, other appropriate evaluations and functional behavioral assessment when behavior impedes learning.[8] This change would provide flexibility to Committees to determine the most appropriate evaluations (e.g., not every student would require a physical evaluation as part of the CSE evaluation.) and could prevent administration of unnecessary tests and examinations. Also, the requirement that a school psychologist determine the need to administer an individual psychological evaluation and provide a written report when such evaluation is determined not to be necessary would be eliminated from State regulation and statute.[9]

- The requirement in law that Boards of Education have plans and policies for appropriate declassification of students with disabilities would be repealed.[10] Regular consideration of whether a student should be declassified is already given at every annual review. The State Education Department notes that the current requirement has not led to increased declassification rates.

- Two changes to the Commissioner’s approval policies would reduce administrative overhead. The requirement in law that the Commissioner of Education, in addition to the Department of Health, approve early intervention services by preschool providers would be repealed and sole responsibility transferred to the Department of Health, the lead State agency for Early Intervention Services.[11] The Commissioner of Education’s role in appointments to State-supported schools and the requirement that State-supported schools conduct student evaluations in addition to the evaluations conducted by the school district would be removed from regulation.[12] This would cut down on duplicative assessments.

These proposals would provide school districts greater flexibility to meet student needs and control spending. One of the core principles of special education is to provide individualized services. Blanket policies that govern district spending and lock in more intensive services than students may need should be abolished. Service quality as measured by student performance should be the indicator of success, not specific staffing ratios.

The Regents are to be commended for their efforts to relieve school districts from burdensome, unnecessary mandates in the face of significant opposition from public employee unions and professional associations throughout the State. The parents of special education students are understandably concerned about changes to regulations that impact their children’s education, but there is no evidence that the pending proposals (or those adopted previously by the Regents) will diminish the quality of special education in New York State. The Regents should approve this third round of mandate relief proposals as is, and the Legislature should follow suit and move swiftly to make the necessary statutory changes.

Footnotes

- For a full list of State special education mandates and how they compare to federal law see http://www.p12.nysed.gov/specialed/publications/partb-analysischart.htm.

- New York State Education Department, Special Education Regulations of the Commissioner of Education Parts 200 and 201, Section 200.1 Definitions, available at http://www.p12.nysed.gov/specialed/lawsregs/sect2001.htm

- At the November 2010 meeting two significant proposals were approved that give more discretion and flexibility to school administrators. First, in certain classrooms, an additional two students will be allowed to be added to “co-teaching” classrooms (above the current limit of 12) in the course of the year with sufficient educational justification for the placement, proof that the instruction of other student is not hindered, and the approval of the Commissioner. Co-teaching classroom students are taught by a general educator and a special educator. Second, the Regents repealed the minimum service requirement for speech and language services for students with disabilities and students with autism. Formerly, at least two 30-minute sessions for speech and language services per week were required; now the duration and frequency of service is at the discretion of the CSE or the CPSE. Other changes included: 1) requiring Boards of Education to keep an “updated” district plan of service for special education rather than requiring that one be prepared every two years; 2) a clarification of requirements for parents’ notification of who will attend CSE or CPSE meetings. For a full description see James P. Delorenzo, Office of Special Education: Office of Special Coordinator for special Education, Special Education Programs and Services: Amendments, December 2010, Available at http://www.p12.nysed.gov/specialed/publications/amend-mandaterelief-1210.pdf

- At the March 2011 Regents meeting additional mandate relief proposals were approved. These included: 1) repealing the requirement for the school district to inform other agencies prior to the graduation or maturity of a student with disabilities; 2) repealing the mandate that the Boards of Cooperative Educational Services establish special education space-requirements plans within a specified time; 3) eliminating written parental consent prior to initial provision of special education services in a 12-month special service program; 4) shortening the statute of limitation on commencement of an impartial hearing from two years to one year and to 180 days if tuition reimbursement for private school is requested; 5) clarification that special classes or integrated co-teaching services do not have to be fully replicated in private school placements; and 6), requiring mediation of due process complaints. For a fuller description of the mandate relief proposals taken up at the Board Meeting see John B. King Jr , The State Education Department, Mandate Relief and Flexibility, March 23, 2011, Available at http://www.regents.nysed.gov/meetings/2011Meetings/April2011/411p12saa1.pdf

- School districts with more than 125,000 inhabitants must appoint subcommittees to the extent necessary to ensure timely evaluation and placement of students with disabilities. Other school districts may, but are not required to, have subcommittees. Subcommittee membership is the same as federal IEP team membership, except a school psychologist is a required member of a subcommittee whenever a new psychological evaluation is reviewed or a change to a program option with a more intensive staff-to-student ratio is recommended. Subcommittees must submit an annual report to CSE. The parent has the right to disagree with Subcommittee recommendations and refer to CSE. Education Law §4402(1)(b)(1)(d) & 8 NYCRR §200.3(c)

- Education Law §4402(1)(b)(1)(a) and (b) and 8 NYCRR §200.3(a)(1)

- CPSE membership can be found in Education Law §4410(3)(a)(1) and 8 NYCRR §200.3(a)(2), and evaluator requirements can be found in §4410(4)(b) and 8 NYCRR §200.16 (c)(1).

- Education Law §4402(1)(b)(3)(a)

- Education Law §4402(1)(b)(3)(a) and 8 NYCRR §200.4(b)(2)

- Education Law §4402(1)(b)(3)(d-2) and 8 NYCRR §200.2(b)(8)

- Education Law §4403(18)

- 8 NYCRR §200.7(d)(1)(ii) and (iii)