New York Should Stop Borrowing from its Pension Funds

Despite $5.4 billion in unexpected revenue from bank settlements and a projected budget surplus for the current year, Governor Andrew Cuomo’s Executive Budget proposes to borrow an additional $1.8 billion from public employee pension funds in coming years. This proposal adds to taxpayers’ long-run costs and risks weakening the fiscal condition of the funds. The State should end this practice, not extend it, and use available bank settlement funds to reduce the outstanding liability from $2.5 billion in past borrowings. Early repayment would reduce interest costs and provide recurring budget savings.

New York’s Long Pension Stretch

For the past four years, New York State has engaged in a form of borrowing from its pension funds technically known as “amortization.” Instead of contributing the amount required by the actuarial rules used by the State Comptroller, the State has deferred a part of the required annual payment. At the time Governor Paterson and the State Legislature approved the plan in 2010, required pension fund payments were projected to increase rapidly owing to heavy investment losses in 2009.[1] During the previous recession the State had also used pension deferrals.[2] While the 2004 deferral was authorized for three specific years, the 2010 law permanently authorized deferrals under specified conditions. Because of recent changes in actuarial assumptions, these conditions currently apply, and the Executive Budget plans borrowing from the pension funds for five more years, through fiscal year 2020.

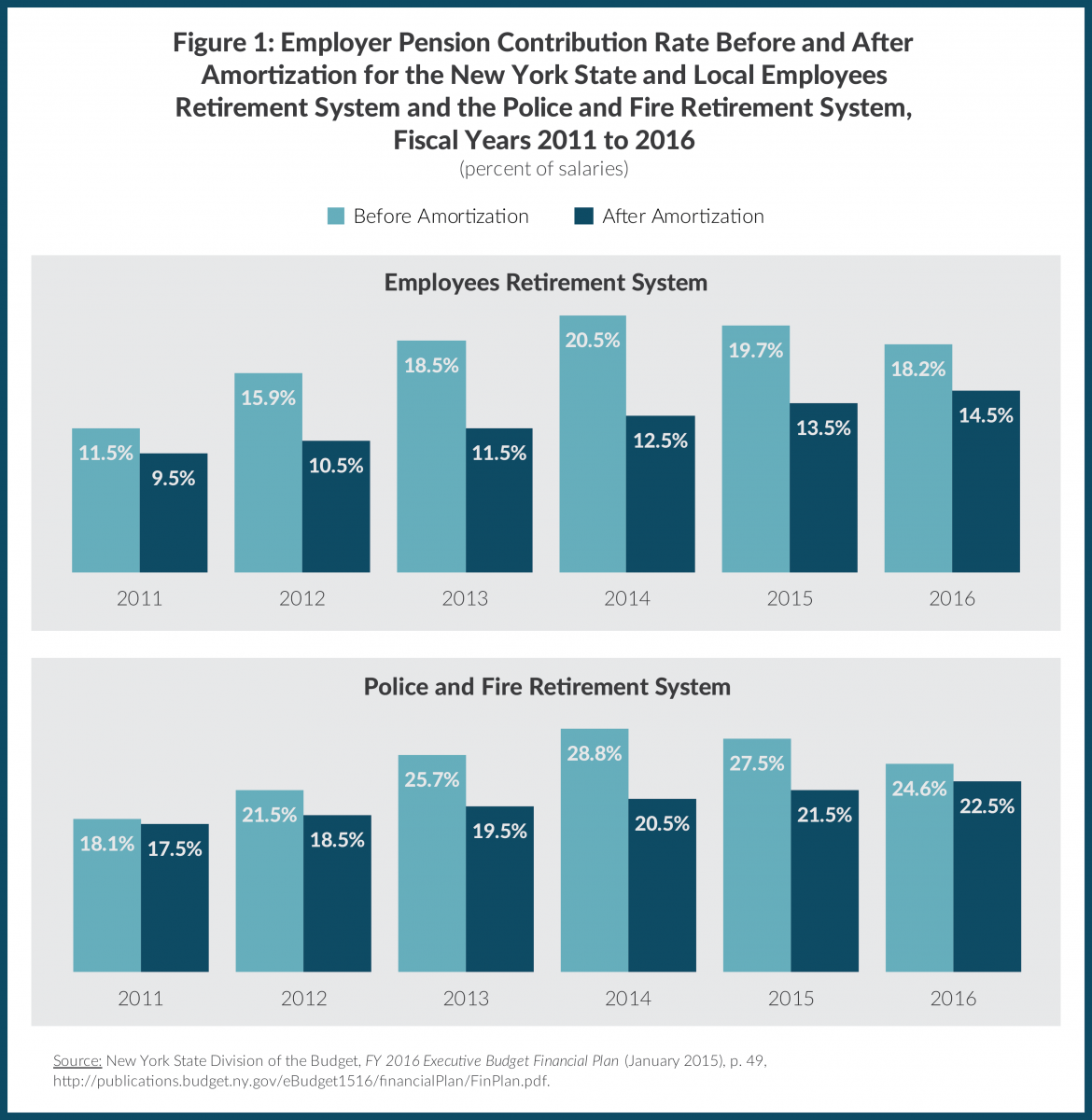

The 2010 enabling legislation sets a percentage threshold above which pension contributions could be deferred, with a 10-year payback period. In fiscal year 2011 required pension contributions in excess of 9.5 percent of salaries for government workers in the New York State and Local Employees Retirement System (ERS), and 17.5 percent of salaries for uniformed workers in the New York State and Local Police and Fire Retirement System (PFRS), could be deferred. The 2010 authorization also allows deferrals in future years if the required contribution rate exceeds a statutory threshold. (See Figure 1.)

The gap between the required contribution rate and the threshold peaked in fiscal year 2014, as investment losses in 2009 were fully recognized under New York’s five-year asset smoothing method. In the current fiscal year, the required contribution rate averages 19.7 percent of salaries for workers in ERS and 27.5 percent for PFRS, while the threshold rates are 13.5 percent and 21.5 percent, respectively. These differences of about 6 percentage points, will allow the State to defer $713 million in payments this year.

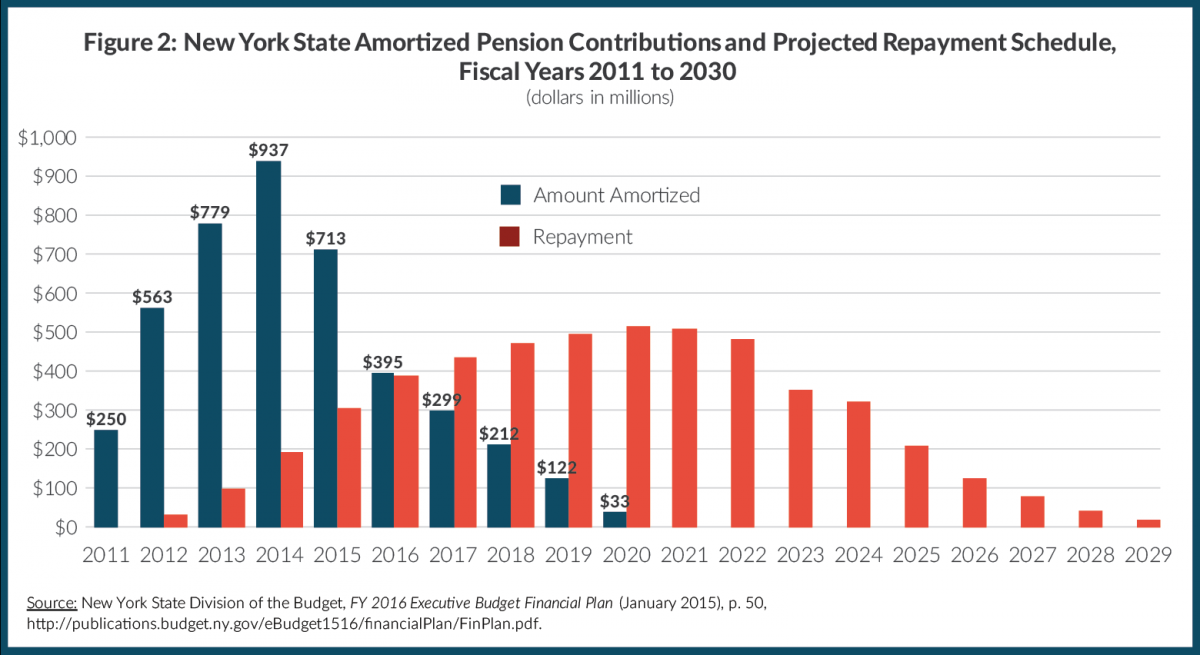

The deferred amounts are treated as a loan and repaid over 10 years at an interest rate set by the State Comptroller based on the return on a fixed-rate investment portfolio. The interest rates for fiscal years 2011, 2012, 2013, and 2014 have been 5 percent, 3.75 percent, 3 percent, and 3.67 percent.[3] The state budget office assumes an interest rate of 3.15 percent for fiscal year 2015 and beyond. Under current projections, the State will amortize a total of $4.3 billion through fiscal year 2020, with repayments stretching to fiscal year 2030; the total amount repaid will likely equal $5.1 billion. (See Figure 2.)

The authorizing law prohibits the contribution rate from declining more than 1 percentage point per year. This requirement was added in response to concerns that the deferral would harm New York’s long-standing practice of fully funding its pension obligations. It protects the pension system from being underfunded in years of high interest rates or strong investment returns. Any excess contributions will first go to repaying deferrals. When repayments are complete, excess funds will be placed in a reserve fund for any future contribution rate increases. When the State adopted its budget last March, the budget office projected the deferrals would end in fiscal year 2015; excess contributions would occur from fiscal year 2017 through 2020; and repayments would end in fiscal year 2025.[4]

However, the State Comptroller last year increased life expectancy assumptions for pension beneficiaries.[5] This update pushed the State’s required pension contribution above the statutory threshold in fiscal year 2016. For ERS the contribution rate increased from 14.2 percent of salaries to 18.2 percent, above the 14.5 percent threshold. Similarly for PFRS the rate increased from 20.8 percent to 24.7 percent, above that fund’s 22.5 percent threshold. Rather than bear the unexpected new cost, which amounts to $355 million next year, the Executive Budget would extend deferrals for five more years, through fiscal year 2020, to yield deferrals totaling $1.1 billion from fiscal year 2016 through 2020.[6]

Short-term Relief, but Long-term Costs and Risks

The pension deferrals provide short-term budget relief but come at a high cost owing to the interest and the lower pension assets. First, the loans are paid back over 10 years with interest. The State has already accrued $144 million in interest costs, despite relatively low interest rates. Under the Executive Budget proposal total interest costs will reach about $780 million.

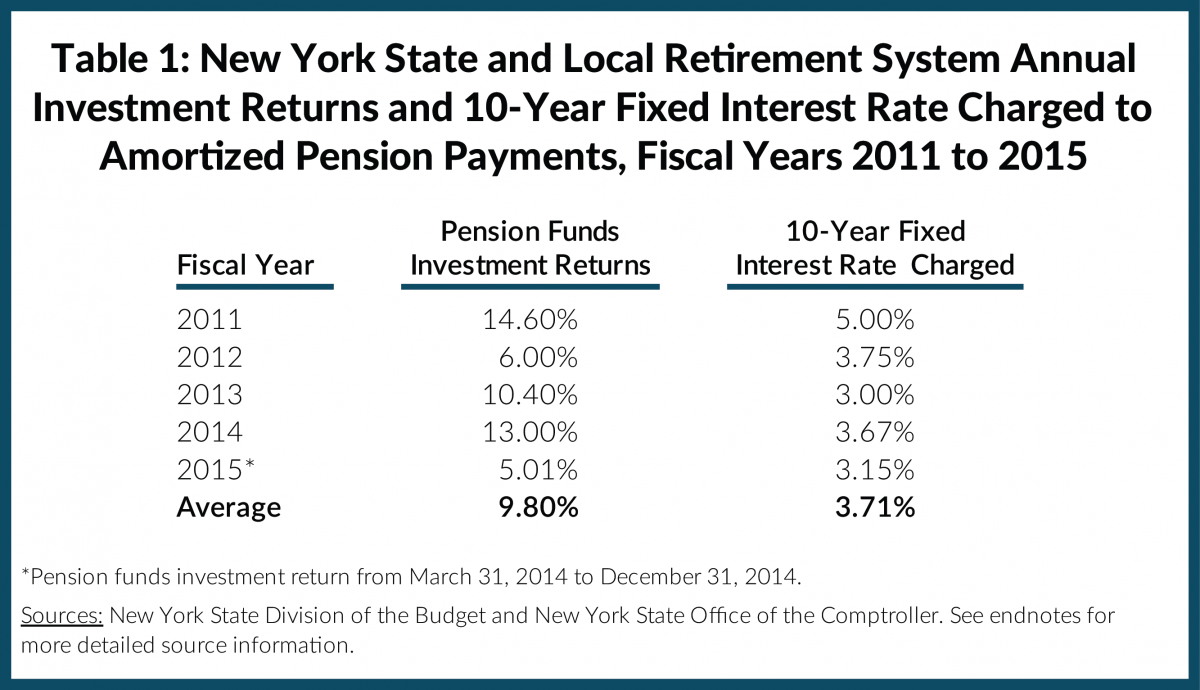

Second, pension fund assets are lower owing to the deferrals, and therefore gains on investments are lower. In the past five years the State’s pension funds have earned an average return of 9.80 percent, more than double the average interest rate of 3.71 percent charged on deferred pension payments.[7] (See Table 1.) The difference in rates over the past five years is equivalent to $260 million in fewer assets in the pension funds. As the loans are paid back over the next 15 years, the difference could be much greater. Assuming the State’s target of 7.5 percent annual rate of return on investments, the pension funds will have $1.6 billion in fewer total assets by fiscal year 2030.

Those lower assets will in turn require higher contributions in the future, perhaps in the midst of the next recession. The sad record of states such as Illinois and New Jersey shows that financing pension obligations through borrowing only makes the problem worse. New York has been among the ranks of fully-funded states, but current law jeopardizes that standing. As of April 1, 2009, New York State’s two main pension funds were more than 100 percent funded; today, the ratio is below 90 percent.[8] The Executive Budget proposal likely will further weaken the funds’ health.

In addition, the Comptroller’s recent change in actuarial assumptions causing higher contributions highlights the risk inherent in allowing the State to defer bearing the full cost of its pension obligations. The required contribution depends on numerous assumptions, including investment returns, salary increases, service length, and longevity. The next five-year experience study of the State’s retirement system will take place in 2015 and may materially alter projections again. Furthermore, last summer the legislature passed and the Governor signed two “pension sweetener” bills.[9] While the cost of these bills is low in the short-term, the ongoing authority to defer payments makes the immediate costs of future enhancements deceptively low.

Conclusion

Although pension borrowing is always ill-advised, in 2010 a rationale existed for deferring payments.[10] In fiscal year 2009, the State’s pension fund investments dropped 26 percent, and in April 2009 New York enacted steep spending cuts and large tax increases to bridge a $20-billion budget deficit. Yet today the State’s fiscal condition is strong. The state budget office projects the current fiscal year, which ends March 31, will close with a general fund cash surplus of $525 million, allowing the State to bolster its reserve funds. New York has also been the recipient of $5.7 billion in settlements with financial firms for a variety of illegal activity, fully $5.4 billion more than expected.

Since 2010 New York State has been borrowing from its pension funds. The State has already deferred $2.5 billion in required payments, and the Executive Budget proposes future deferrals of $1.8 billion through fiscal year 2020. The continued use of this short-term budget relief poses unwarranted risk to the long-term fiscal health of the pension funds.

The State’s first commitment should be to do no more harm and reverse the planned $713 million pension borrowing for this year and the proposed $395 million deferral next year. Second, a portion of the State’s $5.4 billion windfall from bank settlements should be allocated to early repayment of prior-year amortizations. This use of some of the settlement proceeds would be an appropriate use of one-time receipts to pay down debt and maximize the value of the use to taxpayers.[11] Ending the pension borrowing and reducing the State’s liability will avert further risk to New York’s ability to fully fund its pension obligations and provide needed services in the event of a future recession.

By Tammy Gamerman

[1] Citizens Budget Commission, "The State and Local Pension Stretch" (blog entry, June 17, 2010).

[2] “CBC Calls on Governor Pataki to Veto Pension Bill” (press release, July 27, 2004).

[3] New York State Division of the Budget, FY 2016 Executive Budget Financial Plan (January 2015), p. 48, [4] New York State Division of the Budget, FY 2015 Enacted Budget Financial Plan (May 2014), pp. 43-44, http://publications.budget.ny.gov/budgetFP/FY2015EnactedBudget.pdf.

[5] Society of Actuaries, Mortality Improvement Scale MP-2014 (October 2014), www.soa.org/Research/Experience-Study/pension/research-2014-mp.aspx.

[6] New York State Division of the Budget, FY 2015 Financial Plan Mid-year Update (November 2014), pp. 12 and 14, http://publications.budget.ny.gov/budgetFP/FY2015MidYearUpdate.pdf.

[7] New York State Division of the Budget, FY 2016 Executive Budget Financial Plan (January 2015), p. 48, http://publications.budget.ny.gov/eBudget1516/financialPlan/FinPlan.pdf; New York State Office of the Comptroller, New York State and Local Retirement System Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 2014 (September 2014), p. 170, www.osc.state.ny.us/retire/word_and_pdf_documents/publications/cafr/cafr_14.pdf; “NYS Common Retirement Fund Rises to Estimated $180.7 Billion” (press release, August 15, 2014), www.osc.state.ny.us/press/releases/aug14/081514.htm; “NYS Common Retirement Fund Announces Second Quarter Results” (press release, November 26, 2014), www.osc.state.ny.us/press/releases/nov14/112614.htm; and “NYS Common Retirement Fund Announces Third Quarter Results” (press release, February 13, 2015), www.osc.state.ny.us/press/releases/feb15/021315d.htm.

[8] New York State Office of the Comptroller, New York State and Local Retirement System Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 2014 (September 2014), p. 58, www.osc.state.ny.us/retire/word_and_pdf_documents/publications/cafr/cafr_14.pdf.

[9] Citizens Budget Commission, Benefit Sweetener Scorecard 2014 (December 2014).

[10] Citizens Budget Commission, "The State and Local Pension Stretch" (blog entry, June 17, 2010) and “CBC Calls on Governor Pataki to Veto Pension Bill” (press release, July 27, 2004).

[11] Citizens Budget Commission, "Guidelines for Using the $5 Billion Windfall" (blog entry, December 16, 2014).