NYC Revenues in a Recession

Quantifying the Potential Shortfall

Mayor Bill de Blasio’s presentation of the New York City Preliminary Budget for Fiscal Year 2020 rightly cautioned that there will be an inevitable economic downturn. Despite conservative tax revenue forecasts, the potential shortfall from a recession comparable to the last two recessions could be substantial: between $15 billion and $20 billion below projections over three years. Outyear budget gaps could triple to as much as $12 billion in the second year; existing budget reserves of $1.25 billion annually are inadequate to forestall harmful service cuts and tax increases. The Executive Budget for Fiscal Year 2020, expected in April 2019, should reflect constrained spending growth, greater budget reserves, and a substantial increase in recurring savings.

The Economic Climate is Uncertain

There is a growing consensus that the nine-year economic expansion is slowing and the risk of a national recession is increasing.1 In presenting the Preliminary Budget, the Mayor cautioned there could be a recession starting in 2019 or 2020 and specifically cited risks due to volatile stock markets, the threat of foreign trade conflicts, and weakening housing markets.2

Locally, job growth has slowed and the residential housing market has been sluggish. After adding an average of 107,000 private sector jobs annually from 2011 to 2015, job growth decelerated to 66,100 in 2018 and is forecasted to average 50,000 jobs annually between 2019 and 2023.3 Residential sales volume is down for condominiums, cooperative apartments, and one- family homes. While the average price of cooperatives and single-family homes increased in 2018, the average condominium price fell.4

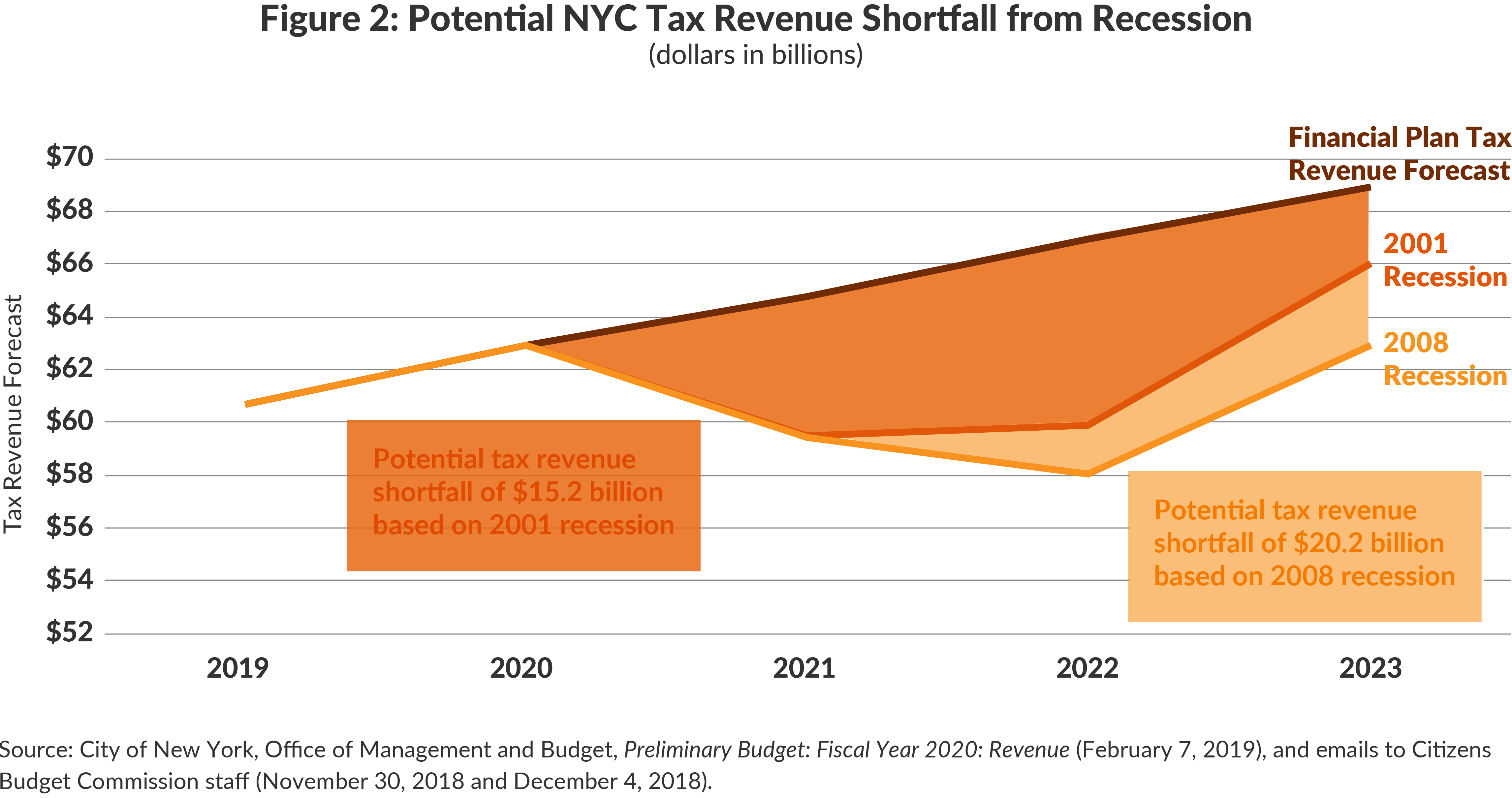

The City’s tax revenue forecast is traditionally cautious and remains so. Taxes are projected to grow from $60.7 billion to $68.9 billion from fiscal years 2019 to 2023, an average annual growth of 3.2 percent.5 Trends for non-property taxes are more indicative of expected economic performance due to their sensitivity to the economic cycle, and the Preliminary Budget projects growth of just 2.2 percent annually through fiscal year 2023.6

The Fiscal Risk is Significant

In both the 2001 and 2008 recessions, tax revenue, adjusted for tax policy changes, declined 5.4 percent the fiscal year after the recession began. During the 2001 recession, tax revenue increased a sluggish 0.5 percent in the second year and 10.2 percent in the third year. During the 2008 recession the revenue loss was more severe, with a 2.4 percent decrease in the second year followed by an 8.4 percent increase in the third year.7

Applying these trends to a hypothetical recession beginning in fiscal year 2020 would result in three-year tax revenue shortfalls between $15.2 and $20.2 billion. (See Figure 1.) In the first year, City tax revenues would fall $5.3 billion below the financial plan (a year-over-year decline of about $3.4 billion). The tax revenue shortfall would be even more substantial in the second year, with revenues $7.1 billion to $8.9 billion below projections. With revenue growth resuming in the third year, the shortfall would narrow to between $2.9 billion and $6.0 billion.

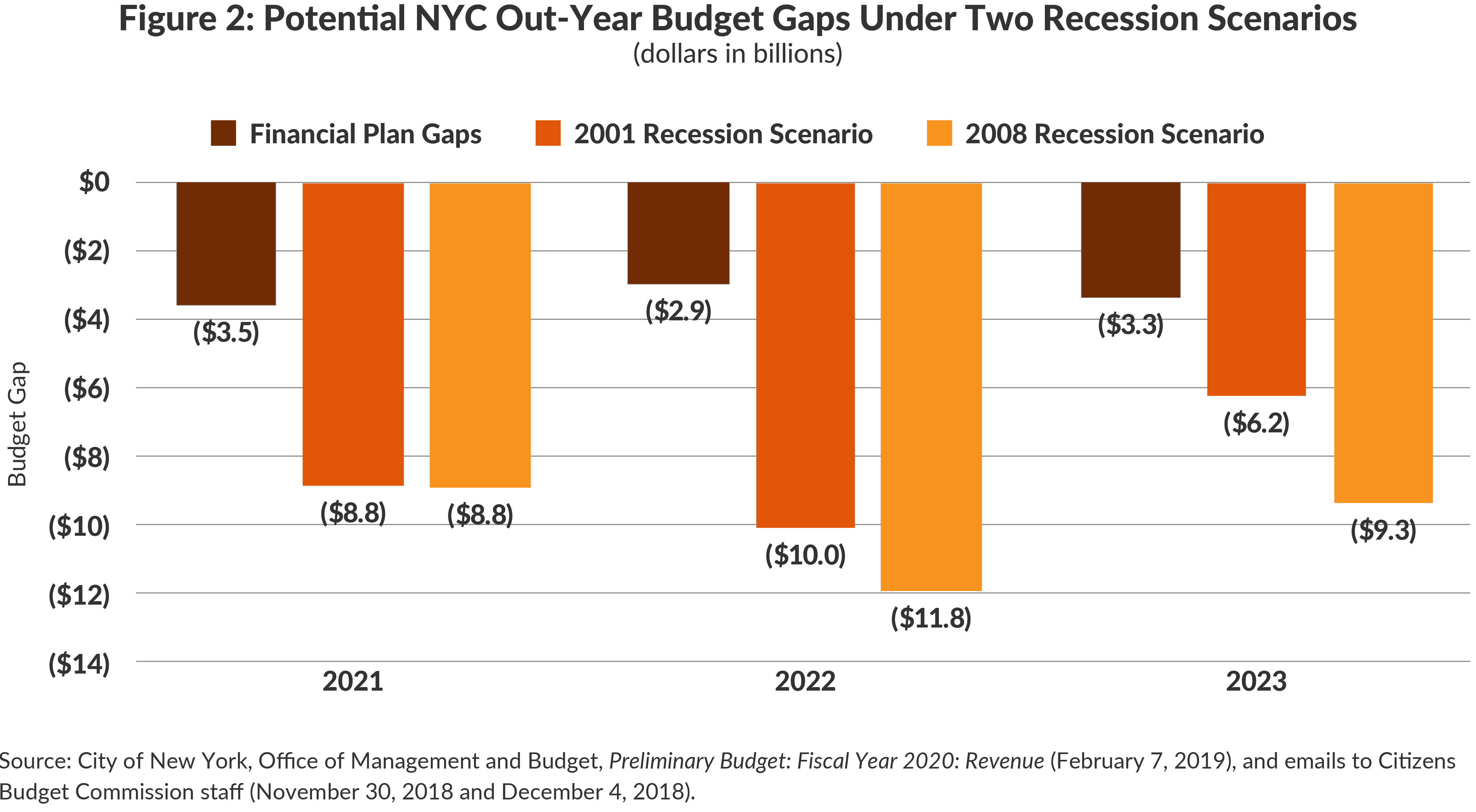

These revenue shortfalls would double or triple the Preliminary Budget’s projected gaps of $3.4 billion, $2.9 billion, and $3.3 billion for fiscal years 2021 through 2023, respectively. The gap in the first year of the recession could reach $8.8 billion, increasing to between $10.0 billion and $11.8 billion in the second year. Cumulative gaps over three years could reach $25 billion under the 2001 recession scenario and $30 billion under the 2008 recession scenario. (See Figure 2.)

Current Reserves are Inadequate

A balanced budget requirement, instituted in the wake of the 1970’s fiscal crisis, prevents the City from establishing a rainy day fund; however, the City has some modest reserves.8 The Preliminary Budget includes $1.0 billion in the General Reserve and $250 million in the Capital Stabilization Reserve annually in fiscal years 2020 through 2023. These resources generally serve as contingency funds for unanticipated expenses; in recent years they have been used to prepay expenses in the subsequent fiscal year.9

The Retiree Health Benefits Trust (RHBT) also has been used as a de facto rainy day fund. The RHBT was established in fiscal year 2006 to accumulate resources to fund the City’s other postemployment benefit (OPEB) liability, primarily for retiree health benefits, estimated at $103.3 billion at the end of fiscal year 2018.10 Using the RHBT as a rainy day fund is inappropriate since it shifts the burden for current OPEB liabilities to future taxpayers. Following the 2008 recession, Mayor Michael Bloomberg nearly depleted the fund by using RHBT resources to balance the budget. The de Blasio Administration has made annual deposits to the RHBT, bringing the balance to $4.5 billion; however, it has signaled its intent to use these funds for general budget relief if necessary. Withdrawals from the fund would be limited to the annual expense for retiree health benefits, which is approximately $2.5 billion in fiscal year 2019.11

The City’s fiscal cushion is insufficient to address revenue shortfalls in a recession. Assuming tax revenue declines similar to those experienced after the 2001 recession, these resources would cover one-third of projected budget gaps: 15 percent with budget reserves and 18 percent with the RHBT. Two-thirds of the gap, $16.7 billion, would need to be closed by other actions.12

The City Should Better Prepare

The City has not sufficiently taken advantage of the long recovery to plan for inevitable economic downturn. With possible cumulative three-year gaps totaling $30 billion, the City should take immediate action to reduce spending growth and increase reserves. Taking action now allows a more thoughtful and analytic approach that can minimize negative impacts on New Yorkers. Mayor de Blasio announced that the Executive Budget would include $750 million in recurring savings. This is the right first step, but would only reduce the cumulative three-year gap by 7.5 percent. The savings will need to be substantially larger to forestall drastic service cuts, when many New Yorker’s will need services most, and counterproductive tax increases in the midst of a recession.

Footnotes

- The Federal Reserve Bank of New York estimated the probability of a recession in the next twelve months at 23.6 percent, up from 15.8 percent in November 2018. See: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Probability of US Recession Predicted by Treasury Spread: Twelve Months Ahead (Updated February 4, 2019, accessed February 21, 2019), https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/capital_markets/Prob_Rec.pdf; City of New York, Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget, February 2019 Financial Plan Detail: Fiscal Years 2019-2023 (February 7, 2019), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/tech2-19.pdf; and Reuters, “Chance of a U.S. Recession Up, Number of Fed Rate Hikes Down: Reuters Poll,” The New York Times (February 14, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/reuters/2019/02/14/business/14reuters-usa-economy-poll.html.

- City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Preliminary Budget: Fiscal Year 2020: Financial Plan Summary (February 7, 2019), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/sum2-19.pdf; and

- City of New York, Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget, February 2019 Financial Plan Detail: Fiscal Years 2019-2023 (February 7, 2019), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/tech2-19.pdf; and CBC staff analysis of data from the City of New York, Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget, NYC Employment Data (NSA)-December 2018 (January 18, 2019), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/csv/nycemploy-nsa12-18.csv.

- City of New York, Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget, February 2019 Financial Plan Detail: Fiscal Years 2019-2023 (February 7, 2019), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/tech2-19.pdf.

- For comparison, actual tax revenue grew 6.0 percent a year from fiscal year 2010 to fiscal year 2018. CBC staff analysis based on Office of the New York City Comptroller, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2018 (October 31, 2018), , and fiscal years 2010 to 2017 editions, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/comprehensive-annual-financial-reports/; and City of New York, Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget, February 2019 Financial Plan: Revenue: Fiscal Years 2019-2023 (February 7, 2019), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/feb19-rfpd.pdf.

- City of New York, Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget, February 2019 Financial Plan: Revenue: Fiscal Years 2019-2023 (February 7, 2019), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/feb19-rfpd.pdf, and February 2019 Financial Plan Detail: Fiscal Years 2019-2023 (February 7, 2019), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/tech2-19.pdf.

- City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, emails to Citizens Budget Commission staff (November 30, 2018 and December 4, 2018).

- The City is required to presented balance budgets and balanced year-end results under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), which does not allow for a rainy day fund because current year expenses must be funded with current year revenues; the use of revenues set aside in previous years would violate GAAP balance.

- If the City has surplus revenues at the end of the year, it prepays expenses for the next year. This process in effect rolls resources across fiscal years while maintaining GAAP balance.

- Thad Calabrese, The Price of Promises Made: What New York City Should Do About Its $95 Billion OPEB Debt (Citizens Budget Commission, October 25, 2017), https://cbcny.org/research/price-promises-made.

- City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Preliminary Budget: Fiscal Year 2020: Departmental Estimates (February 7, 2019), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/de2-19.pdf .

- Historically the City has closed budget gaps during recessions by increasing taxes, reducing spending, and receiving additional intergovernmental aid.