Let a Sleeping Tax Lie

New York Should Reject Proposals to Reinstate the Stock Transfer Tax

This year, New York State faces a $8 billion budget gap. Next year, the gap is expected to grow to $17 billion. Some policymakers and advocates have advocated reinstating the stock transfer tax (STT) as one way to raise more money for the State.1 In fact, New York has had a stock transfer tax for 115 years, but it has been effectively dormant for the last 40 because everyone who pays the STT receives a full refund. If the rebate were eliminated, essentially putting the tax back into effect, New York would become the only state to impose such a tax on the sale and transfer of stock. Both publically traded companies and anyone in New York who saves money in a retirement or college savings fund would feel the impact.

Advocates claim the tax could yield up to $13 billion in annual revenue, based on data from past years. The record from fiscal year 2020, however, shows collecting the STT this past year would only have yielded $4 billion, just a third of advocates’ estimate.2 In fact, the State would likely amass even less, since firms might avoid the tax by using new technology or relocating the trading portion of their businesses outside New York. While tax avoidance could yield disappointing revenue on the newly reinstated tax, relocation of securities industry jobs outside of New York would harm the State’s employment opportunities and tax collections. Policymakers should leave the STT dormant and find alternative ways to fill the budget gap.

The Stock Transfer Tax in New York

New York’s STT, a type of a financial transaction tax (FTT) levied on the trade of stocks, originally took effect in 1905. Later, lawmakers increased the amount collected, but by the late 1970s, the tax had fallen out of favor. Beginning on October 1, 1979, the State returned 30 percent of the tax through a rebate, and two years later, on October 1, 1981, effectively eliminated the tax by increasing the rebate to 100 percent.3

Since then, most potential taxpayers have neither had to pay the tax nor await a refund. The vast majority of transactions are simply recorded and no tax is collected. Any sale or transfer of stock, agreements to sell stock, memoranda of sales of stock, certificates of stock, certificates of rights to stock, certificates of interest in property or accumulations, certificates of deposit to purchase a stock, and certificates of interest in business conducted by trustees, or any trade involving shares in corporations or partnerships that occurs in New York State is subject to the STT.4

Certain small transactions made by individuals, like buying shares in a cooperative housing corporation as part of buying an apartment, represent a very small share of trades subject to the STT. To pay, people purchase physical stamps from the State Department of Taxation and Finance, affix the stamps to the bill of sale, cancel the tax stamps so they cannot be used again, and then request a rebate from the Tax Department. The tax on trades flowing through the New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ is electronically administered by a third-party entity and no money changes hands.5

Importance of the Securities Industry to New York

New York is highly dependent on the securities industry, which accounted for approximately 18 percent of State tax collections and 6 percent of City tax collections in fiscal year 2020. Despite the importance of the industry to New York, there is evidence that New York is losing its dominance in the sector: between 1990 and 2019 New York City’s share of national securities employment decreased from 33 percent to 19 percent. State tax policy changes, such as instituting the STT, would hasten New York’s smaller share of securities employment.[6]

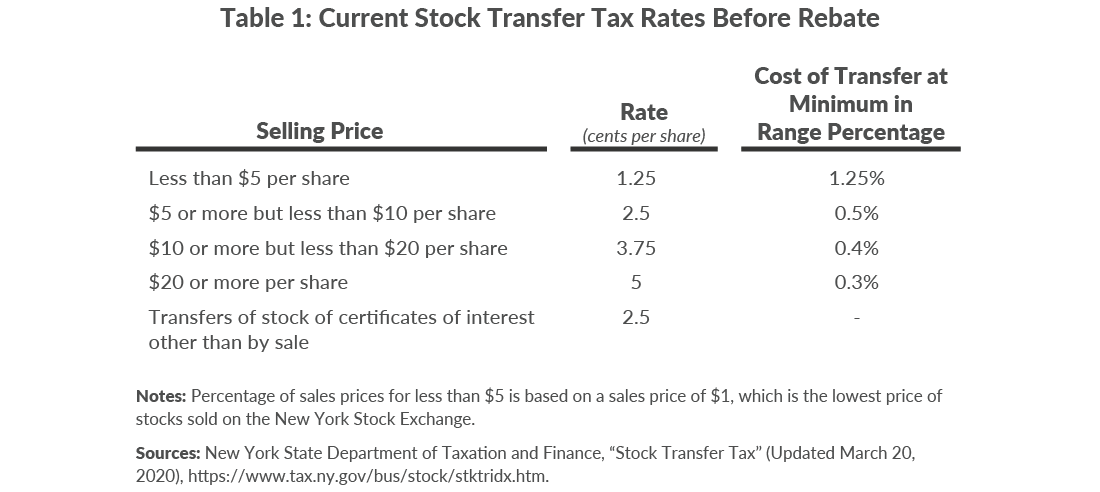

The STT is calculated on the dollar value of the stock being transferred, with a minimum tax of 1.25 cents per share on shares costing less than $5, and a maximum tax of 5 cents per share on shares costing more than $20. The tax (before rebates) imposes a greater liability on stocks of smaller value, with a $1 stock subject to a 1.25 percent tax on every sale, whereas a $20 stock is subject to a tax of 0.3 percent. (See Table 1.) A stock traded for $1,000 per share would incur a tax of 0.005 percent. There is a maximum tax of $350 per transaction if the trade is of the same class of stock from the same issuer on the same day.7 Once this maximum is met, the cost per trade in taxes decreases proportionally.8

Entities subject to the tax include hedge funds, high-frequency traders, and the ultra-wealthy, as well as union retirement funds, mutual funds managed by large trading houses, 401(k)s and Individual Retirement Accounts, and college savings accounts.

For New York, the key provision of the STT is that it applies when the transaction takes place in the State, regardless of the home or business location of the buyer or seller, unlike other types of transaction-based taxes. According to the New York State Rules and Regulations, a transfer is taxable if the following happen within New York State: sale; delivery of the certificates; or transfer effectuated by recording the transfer in corporate books. The person or company that originates the sale is liable for the tax, but the buyer and seller share responsibility for ensuring the tax is paid.9 Parties to the transaction may agree which of them shall bear the liability.10

In 2020 the vast majority of trades happen online, a problem for determining where a transaction takes place and therefore whether it is taxable in New York. Because the STT has not generated any tax revenue for decades, the State has not set up meaningful guidance on this issue, leaving open the question of whether a transaction executed on an out-of-state computer server would have a tax liability in New York; neither law, regulation, nor litigation provide clarity. Given technological advancements and changes in the securities industry, companies could likely avoid paying the tax if it were reinstated without establishing new rules regarding liability and location.

Currently no states impose a FTT. The federal government collects a small FTT of 0.00221 percent or $22.10 per million dollars of trades.11 The fee is semi-annually calculated and covers the costs of operating the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Impacts of the STT on New York

1. Firm Relocation

When the State’s STT went into effect in 1905, stock trading required someone’s physical presence to buy and sell at one of a limited number of stock exchanges throughout the world. Traders in New York, for example, could not easily uproot their businesses to other cities with stock exchanges, and so the State’s long-ago tax did not push firms to move away. Now, electronic trading platforms allow trades to be initiated anywhere, and New York can no longer count on traders and brokers needing to stay. The securities industry also requires brokers to seek the “best execution” of trades on behalf of clients; they would be duty-bound to find the best prices for a client and would always have to consider the STT when determining where to purchase stocks.12 Likewise, if inclusion of a New York-based entity subjects the transaction to taxes, out-of-state investors would have a financial incentive to avoid New York based brokers and securities owned by New Yorkers would be more expensive to purchase. By making trading in New York less competitive compared to other states, the renewed STT will provide an incentive for firms to relocate. While the securities industry in New York City boasted pre-tax profits of $27.3 billion in 2018, a tax bill as large as advocates claim could impact firms’ profitability and encourage them to move to other states.13

When Sweden introduced a 2 percent STT in 1984, the country quickly saw an outflow of trading activity: 30 percent of all trading in listed Swedish companies moved from the Stockholm Exchange to the London Exchange because the United Kingdom imposes a FTT at a much lower rate. (After the election of the opposition party, the tax was abolished in December 1991.14) Similarly, after France imposed a STT in 2012, trade volume decreased 16 percent.15 Germany also temporarily imposed a FTT but repealed it based on the impact on trading.16 As noted by the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, “FTTs decrease capital markets activity as volumes migrate. This can lead to not only a decrease in taxable revenue but also to a decline in economic activity, jobs and GDP contribution.”17

There are some countries that do impose an FTT, like the United Kingdom, whose tax is 0.5 percent (with an effective tax rate of 0.1 percent because of various exemptions and tax avoidance strategies).18 But New York would be the only state in the United States to impose the tax, and if companies were willing to relocate from one country to another to avoid a STT, they would move from one state to another.

2. Disappointing Revenues

Every trade that leaves New York because of the STT would decrease the revenue the State expects to bring in by instating the tax, and it is easier than ever for New York companies to run their transactions in other states. Technology has advanced since the STT rebate effectively ended the tax in 1981, making it very common to process trades away from New York’s physical trading floors. For example, the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) now processes most trades through its Mahwah, New Jersey data center.19 In recent weeks, in response to reports that New Jersey may be considering levying a STT on transfers processed in New Jersey, NYSE has announced that it will temporarily process a subset of trades through its backup computer system in Chicago to highlight its mobility.20 NYSE, notably, is owned by a multinational corporation that also owns exchanges throughout the world. This global structure could make it straightforward to move the location of any given stock sale or transfer out of New York. Similarly, NASDAQ is considering moving its computer servers from New Jersey to Texas.21

Under the law, trades moving through processors outside New York would not be taxable if the entities purchasing, selling, and facilitating the trade were all located outside the state. Currently, the State has not specified if it counts such transactions when it reports on the theoretical stock transfer revenues that would be collected without the rebate. In the case that one or more parties in a trade are based in New York but the trade itself is processed outside New York, that trade may not be a taxable transaction. Either way, enforcement would be a challenge.

3. Disproportionate impact on some financial instruments and traders

The STT would disproportionately burden certain segments of the securities industry over others. Mutual funds, in particular, use frequent regular transfers to keep the ratios of their holdings steady when values of stocks change. But these transfers would now be subject to the STT, increasing costs for investors of mutual funds, many of whom are not wealthy individuals. High frequency traders (HFT) are another group who would be affected by the tax. Their trading strategy relies on making small gains on many individual transactions, each of which would now be subject to an additional fee.22

4. Unintended taxpayers

Large securities firms would not be the only ones paying the new tax on trades. Reinstating the tax would also increase New Yorkers’ cost of investing in stocks or index funds to save for retirement or a child’s college education. Because this tax is transaction-based and not income-based, it will increase costs regardless of a taxpayer’s income or whether the taxpayer is losing money from a taxed stock sale.

Proposals to Reinstate the STT

Three bills to reinstate the tax are pending in the New York State legislature. Two of these bills—S.3315 (Myrie) and A.7086 (Dilan)—would reduce the STT rebates, dedicate the revenue to specific purposes, and maintain the current tax base. A.7791b (Steck)/S.6203a (Sanders) would completely repeal the rebate and expand the base of the tax.

- S.3315 (Myrie) would decrease the current rebate from 100 percent to 60 percent and provide revenue to the Dedicated Infrastructure Investment Fund, which generally has received monetary settlement funds and been used for housing and economic development. By reducing the rebate from 100 percent to 60 percent, the State would be imposing taxes at 40 percent of the rates outlined above, although the $350 maximum would remain in place.

- A.7086 (Dilan) would decrease the current rebate from 100 percent to 80 percent and dedicate the revenue to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). By reducing the rebate from 100 percent to 80 percent the State would be effectively imposing taxes at 20 percent of the rates outlined above, although the $350 maximum would remain in place.

- A.7791b (Steck)/S.6203a (Sanders) would repeal the current rebate completely and expand the type of transaction taxed to include trades where any action related to the trade takes place within the state or if a party involved in the transaction works or lives in New York State. The $350 maximum daily tax would remain in place. In fiscal year 2022, all revenue collected from this tax would be deposited into the State’s general fund. In fiscal years 2023 and beyond, revenues would be distributed as follows:

- 25 percent to the MTA;

- 15 percent to the highway and bridge capital account;

- 15 percent to clean energy fund;

- 10 percent to the dedicated highway and bridge trust fund;

- 10 percent to the division of housing and community renewal;

- 5 percent local infrastructure account for the Consolidated Local Street and Highway Improvement Program (CHIPS);

- 5 percent to the local infrastructure account for safe water and infrastructure action program;

- 5 percent to the municipal assistance state aid fund;

- 5 percent to non-MTA dedicated mass transportation trust fund; and

- 5 percent to upstate transit systems.

Potential Impact of the STT Bills

The two bills that reduce the STT rebates, S.3315 & A.7086, would result in fewer transactions and minimal revenues in New York. Because these two proposals would leave in place the current definition of a transfer within the state, transfers processed out-of-state would most likely not be subject to the tax. Therefore, traders would have an incentive to shift trade processing out of New York, reducing potential revenue.23

The impact of A.7791b/S.6203a would be greater and could push jobs to leave New York, since the bills would expand the STT to apply to any trade that includes a New York party. This would put New York businesses and individual investors at a competitive disadvantage by increasing the price of stock purchased on a New York-based exchange, sold through a New York based broker, or from a New York-based seller compared to traders located outside New York. That could force not only businesses but also residents to leave for other states. Unlike the other proposals that would only reduce rebates, expanding the definition of what is considered a taxable transaction would require firms to physically move their trading operations out of state to reduce their tax liability. This proposal may raise considerably more revenue than the others in the short term, but once businesses move out of the state, collections will decrease and securities jobs and their associated benefits would disappear.

Conclusion

Repealing or reducing STT rebates is unlikely to significantly increase State tax collections. If the tax goes back into effect as written, many trades would simply move to other states to avoid the tax. But if the applicability of the tax is expanded to include all trades initiated by New Yorkers or New York-based firms (as is proposed in A.7791b/S.6203a), it would put New York securities firms at a competitive disadvantage and increase costs for New Yorkers with stock or mutual fund investments. New York’s budget gaps are real, but projected revenues from reviving the STT are not. New York’s leaders should reject proposals to revive the STT.

Footnotes

- Michael Gormley, “As Albany waits for federal aid, some weigh taxes on rich,” Newsday (May 18, 2020), https://www.newsday.com/news/health/coronavirus/state-legislature-tax-rich-1.44690253.

- New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, “Table 20: Local Taxes Collected by the Department of Taxation and Finance—State Fiscal Years 1991-2020” (Annual statistical report of New York State tax collections statistical summaries and historical tables fiscal year 2019-2020, updated August 7, 2020), https://www.tax.ny.gov/pdf/2019-20_Collections/table%2020.xlsx.

- The tax was rebated instead of repealed because the tax is tied to New York City’s municipal assistance corporation bonds with any excess funds flowing to the City of New York’s general fund. Repealing the tax would have created problems for the bond holders. See: section 92.b of the New York State Finance Law.

- New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, “Stock Transfer Tax” (updated March 20, 2020), https://www.tax.ny.gov/bus/stock/stktridx.htm; and New York State Rules and Regulations, NYCRR 20.I.50.1 (accessed June 22, 2020), https://govt.westlaw.com/nycrr/Document/I50e63977cd1711dda432a117e6e0f345?viewType=FullText&originationContext=documenttoc&transitionType=CategoryPageItem&contextData=(sc.Default)

- The Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation administers the tax on behalf of NASDAQ and NYSE. See: “The Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation,” NASDAQ Glossary (accessed October 5, 2020), https://www.nasdaq.com/glossary/d/depository-trust-and-clearing-corporation.

- Office of the New York State Comptroller, The Securities Industry in New York City (October 2020, accessed October 27, 2020), pp. 1-8, https://www.osc.state.ny.us/files/reports/osdc/2020/pdf/report-6-2021.pdf.

- See section 270-e of the New York State Tax Law.

- The current daily maximum provides a tax advantage for entities purchasing large quantities of the same stock on the same day. For example, a trader purchasing a $20 stock would pay $350 in STT if they are buying 7,000 shares or 700,000 shares, with the trade of 7,000 shares paying $0.05 per share and the 700,000 share trade paying $0.0005 per share.

- New York State Rules and Regulations, NYCRR 20.I.50.3 (accessed June 22, 2020) https://govt.westlaw.com/nycrr/Document/I50e6397dcd1711dda432a117e6e0f345?viewType=FullText&originationContext=documenttoc&transitionType=CategoryPageItem&contextData=(sc.Default).

- New York State Rules and Regulations, NYCRR 20.I.50.3 (accessed June 22, 2020) https://govt.westlaw.com/nycrr/Document/I50e6397dcd1711dda432a117e6e0f345?viewType=FullText&originationContext=documenttoc&transitionType=CategoryPageItem&contextData=(sc.Default).

- United States Security and Exchange Commission, “Fee Rate Advisory #2 for Fiscal Year 2020” (January 9, 2020), https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2020-7.

- U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, Best Execution (Fast Answers, May 9, 2011), https://www.sec.gov/fast-answers/answersbestexhtm.html.

- Office of the New York State Comptroller, The Securities Industry in New York City (October 2019, accessed June 29, 2020), https://www.osc.state.ny.us/sites/default/files/reports/documents/pdf/2020-01/report-9-2020.pdf.

- Jonathan A. Schwabish, “The Stock Transfer Tax and New York City: Potential Employment Effects” (Partnership for New York City, December 2004), p. 3, https://www.pfnyc.org/reports/2004_12_stock_transfer_tax.pdf.

- The French STT requires that “[t]he respective security has to be issued by a company with registered office in France and exhibit a market capitalization larger than e1 billion evaluated by January 1st of the preceding year of taxation. In contrary to comparable taxes, the French STT is therefore limited to the most liquid French equity instruments.” See: Martin Haferkorn and Kai Zimmermann, “Securities Transaction Tax and Market Quality – The Case of France” (January 4, 2013), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2229221.

- Aaron Klein, “What is a Financial Transaction Tax?” (Brookings Institution, March 27, 2020), https://www.brookings.edu/policy2020/votervital/what-is-a-financial-transaction-tax-2/.

- Katie Kolchin, “Ramifications of an FTT A Financial Transaction Tax Will Harm US Capital Markets & Individual Investors” (SIFMA Insights, October 2019), p.10, https://www.sifma.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/SIFMA-Insights-Ramifications-of-an-FTT.pdf.

- Countries imposing a FTT include China, Cyprus, Egypt, Honk Kong, Ireland, Malta, Pakistan, Singapore, Switzerland, Thailand, Trinidad & Tobago, UK, Brazil, Finland, France, Italy, Venezuela, India, South Africa, South Korea, Taiwan, Belgium, Philippines, and Poland. See: Katie Kolchin, “Ramifications of an FTT A Financial Transaction Tax Will Harm US Capital Markets & Individual Investors” (SIFMA Insights, October 2019), p. 13, https://www.sifma.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/SIFMA-Insights-Ramifications-of-an-FTT.pdf.

- Corey Johnson, “NYSE Isn't Really in NY, It's in Mahwah NJ,” Bloomberg News (July 8, 2015), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/videos/2015-07-08/nyse-isn-t-really-in-ny-it-s-in-mahwah-nj.

- Alexander Osipovich and Joseph De Avila, “NYSE Signals It Will Exit New Jersey if State Taxes Stock Trades,” Wall Street Journal (September 11, 2020), https://www.wsj.com/articles/nyse-signals-it-will-exit-new-jersey-if-state-taxes-stock-trades-11599829203?mod=lead_feature_below_a_pos1.

- Dom DiFurio, “Nasdaq In Talks With Gov. Abbott About Relocating Trading Systems to North Texas,” (Dallas Morning News (October 7, 2020), https://www.nbcdfw.com/news/business/nasdaq-in-talks-with-gov-abbott-about-relocating-trading-systems-to-north-texas/2456582/.

- Potential negative market impacts of high frequency trading will not be avoided if the industry moves out of New York in response to this tax; however, the economic impact on New York will be immense. Entities such as cooperative housing corporations and partnership transfers would be less able to avoid the tax by shifting the location of the transaction.

- Entities such as cooperative housing corporations and partnership transfers would be less able to avoid the tax by shifting the location of the transaction.