NYCHA 2.0: Progress at Risk

Last December the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) released NYCHA 2.0, a strategic plan to preserve its deeply affordable housing and address its $32 billion five-year capital need. The plan identified strategies to fund $24 billion in capital repairs over 10 years, clear the lengthy maintenance backlog, and prioritize repairs to ameliorate conditions that cause health and safety problems. While it will not address all of NYCHA’s capital and operating needs, NYCHA 2.0 provided a roadmap to a better future for NYCHA and its residents.

This report reviews NYCHA’s progress implementing NYCHA 2.0. The report has four key findings:

- NYCHA is on pace to meet its short-term target for increasing public-private partnerships to fix and manage NYCHA housing; however, it will not be able to meet its long-term goal of converting 62,000 units without shifts in the allocation of state and local housing funding, federal regulatory relief, and additional federal funding;

- NYCHA’s efforts to increase the number of mixed-income “infill” development projects and tap into the value of transferrable development rights have largely stalled due to resistance from some public officials and community organizations;

- NYCHA’s efforts to close the repair backlog have failed thus far to stem the growth in work orders, and efforts to modernize work rules and schedules have yielded some successes but have been accompanied by increased labor costs; and

- Long-promised state funding and federal regulatory relief have yet to materialize.

In sum, NYCHA has made some progress, but its prospects remain tenuous without the cooperation and support of local, state, and federal officials, labor unions, and the private sector. While some of these partners have stepped up, others have resisted much-needed reforms—and the costs of these delays are stark. Holding up revenue-raising projects negatively affects the quality of life for tenants already living in poor conditions, perpetuates or accelerates NYCHA’s physical deterioration, and increases rehabilitation costs. Without the funding anticipated from NYCHA 2.0 initiatives, more than 4,000 units each year could go without repairs; many will reach the point at which they are at risk of being no longer cost-effective to repair.

These challenges highlight the importance of successful implementation of NYCHA 2.0 and the potential impact of failure.

NYCHA 2.0 Initiatives

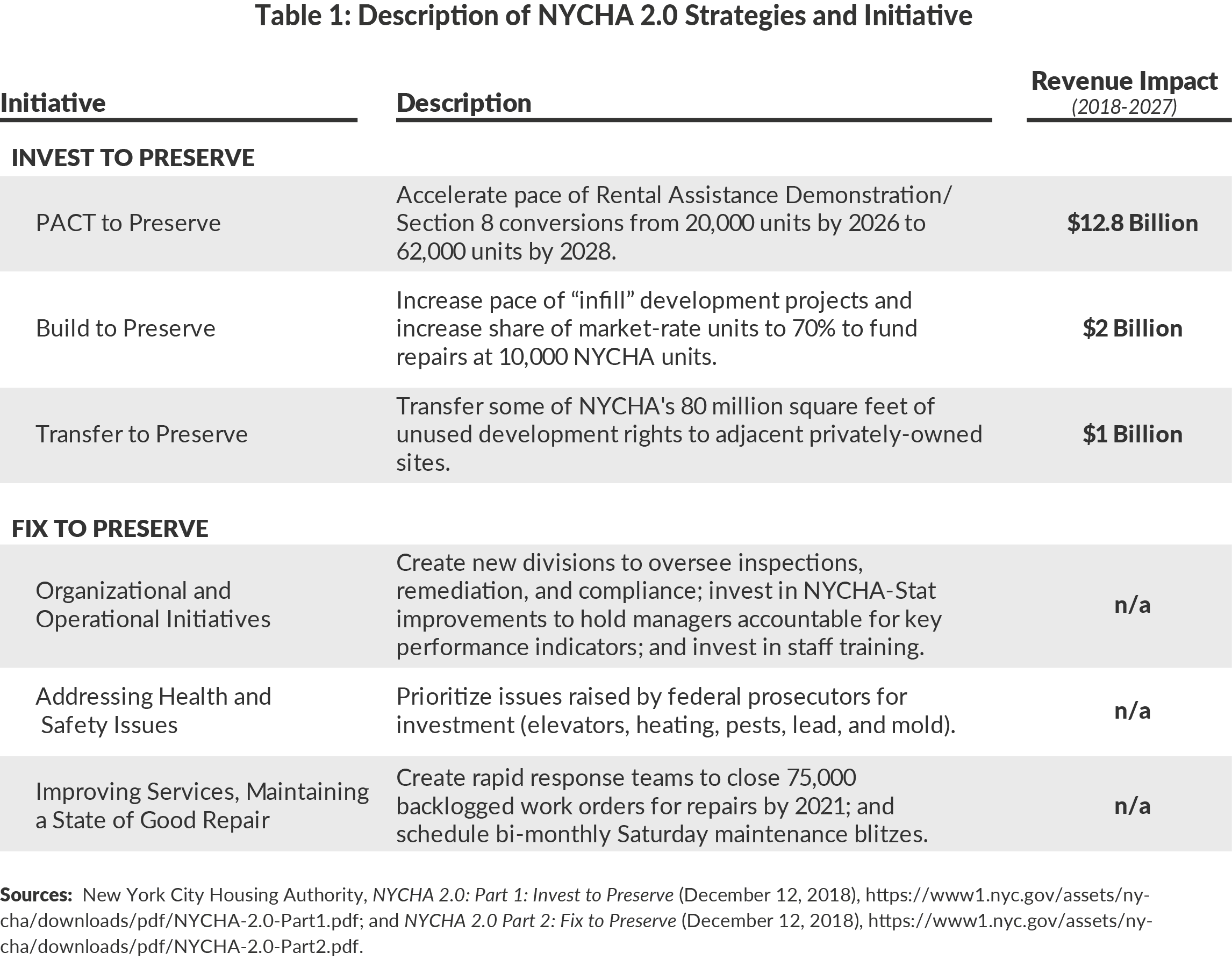

NYCHA 2.0 includes two strategies. (See Table 1.) The first, “Invest to Preserve,” is comprised of plans to raise funding for capital repairs through public-private partnerships and the sale of unused development rights. The second, “Fix to Preserve,” encompasses initiatives to address long-standing health and safety issues and basic maintenance needs by promoting a culture of accountability, improving coordination of repair work, and boosting inspection and compliance units.

The plan relies on $23.8 billion in funding over 10 years to address NYCHA’s five-year capital needs totaling $31.8 billion. Invest to Preserve initiatives generate most of the funding, including $12.8 billion from accelerating the pace of public-private partnerships under the Permanent Affordability Commitment Together (PACT) program, $2 billion from additional infill development with a higher share of market-rate housing than previously proposed, and $1 billion from the sale of transferrable development rights. (See Table 1.) The plan also assumes the receipt of $7.9 billion in existing funding, including: $3.6 billion in federal funding; $2.2 billion in City funding over 10 years required under the City’s agreement with federal prosecutors and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD); $1.4 billion in City capital funding over five years for Mayor’s Initiative programs to repair roofs, boilers, and other essential equipment; and the receipt of $450 million that has been appropriated but not yet released by the State.1

Invest to Preserve Initiatives

PACT to Preserve

The Citizens Budget Commission’s (CBC's) 2018 report Stabilizing the Foundation recommended NYCHA transition from being a landlord to being an affordable housing steward that directly manages fewer buildings. Public-private partnerships are essential to accomplishing this. NYCHA’s plan to take significantly greater advantage of public-private partnerships through the Permanent Affordability Commitment Together (PACT) program—comprised of Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) projects and project-based Section 8 conversions—is the best option to preserve NYCHA’s housing.

NYCHA 2.0 anticipates addressing $12.8 billion in capital needs by 2028 by converting 62,000 units through PACT, with an estimated pipeline of projects that ramps up from approximately 4,000 annually in the years between 2019 and 2023 to more than 7,000 units annually by 2026. While NYCHA is making reasonable progress on the PACT to Preserve initiative, it will not meet the 62,000-unit goal without additional federal and city legislative actions, as well as funding—all of which are uncertain.

About RAD

The Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program is a federal program that allows public housing authorities to apply to HUD to convert the funding stream for units from federal public housing subsidies, established under Section 9 of the Housing Act of 1937, to an equivalent amount in rental housing voucher funding, established under Section 8 of the Housing Act. Section 8 permits housing authorities to take out loans or issue bonds backed by the subsidies to pay for repairs; in contrast, Section 9 largely prohibits housing authorities from issuing debt on their buildings. Housing authorities can also enter into partnerships with private property managers to renovate and operate properties that convert to Section 8 through the RAD program.

NYCHA has focused first on converting small, scatter-site developments and on properties built by the City and State that currently do not receive federal aid. Prioritizing these properties for RAD conversions makes sense. Scatter-site developments, with about 10,000 total units, are inefficient to operate and have the highest per-unit capital needs in NYCHA’s portfolio.2

There are also eight remaining developments with a total of 5,694 units that were built by the City or the State and are not subsidized by federal funds. In 2018 NYCHA diverted $23 million in federal funds from other properties to subsidize these properties’ operating costs. NYCHA slowly has been converting these units to Section 8 funding streams; accelerating their conversions through PACT will free up funding to be used at other developments.3

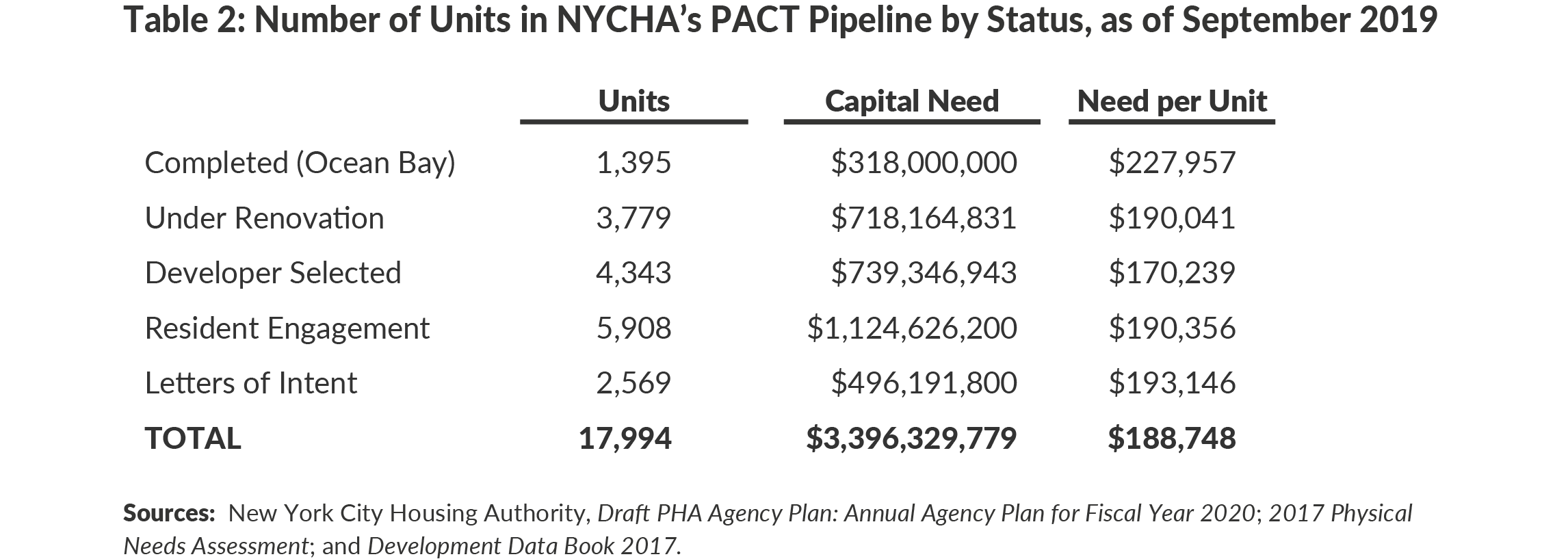

NYCHA is almost on track to achieve the first phase of its PACT conversion goal. NYCHA expects to close RAD contracts on 17,994 units with $3.4 billion in five-year capital needs by 2022, a pace slightly below what is needed to meet the NYCHA 2.0 goal. In addition to the 1,395-unit Ocean Bay development, which entered the RAD program in 2017, 3,779 units are now under renovation through the PACT program. Developers have been selected for deals covering another 4,343 units, with closings likely to occur in late 2019 or early 2020. NYCHA has begun resident engagement on 5,908 units and given notice to HUD of its intent to convert an additional 2,569 units.4

Sustaining this momentum and further accelerating the pace of conversions from 4,000 to 7,000 units annually will be hard for two reasons: federal law caps the number of RAD conversions; and NYCHA’s financing model is not replicable across the entire portfolio.

RAD Conversions are Capped

Congressional authorization of the RAD program caps the number of conversions nationally at 455,000 units, even though there are more than 1 million public housing units nationwide. As of September 2019, 259,713 units have closed or have HUD-approved letters of intent, representing 57 percent of the RAD cap.5 NYCHA will have to compete with other housing authorities for the remaining 43 percent. There likely remains enough capacity to complete the conversion of NYCHA’s near term pipeline, but Congress will need to increase or remove the cap on RAD conversions if NYCHA is to convert additional units in the future.

Financing Model is Not Replicable

Even if Congress lifts the RAD cap, NYCHA may not be able to finance the rest of its projected PACT pipeline without a shift in the allocation of City and State housing financial support or increases in federal funding.

RAD transactions generally need a public subsidy in addition to funds raised by the RAD funding streams in order to be financially feasible. (See Stabilizing the Foundation for more detail on how the RAD program works.) Most RAD properties that require moderate or substantial rehabilitation rely on a combination of tax-exempt bonds and Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) equity plus grants or below-market subsidy loans to fund needed renovation.

Instead of relying on bonds, tax credits, and public subsidies, however, NYCHA has financed most of its RAD conversions to date using private loans and developer equity backed by a mix of RAD and other federal subsidy programs.6

NYCHA’s private partners have been able to use private loans because NYCHA secured permission from HUD to use two alternative subsidy programs as part of its PACT program: Tenant Protection Vouchers (TPVs) for conventional federally-funded units and project-based Section 8 vouchers for NYCHA’s remaining unfunded units. TPVs are available under a section of the federal public housing law commonly referred to as Section 18, which covers the disposition of public housing units that are obsolete and no longer cost effective to repair. TPV rental vouchers fund the difference between 30 percent of tenants’ incomes and 110 percent of fair market rents, which is substantially greater than the subsidy offered under RAD, which funds the difference between incomes and the federal public housing subsidies. Under recently approved federal rules, housing authorities can secure TPVs for up to 25 percent of units included in a RAD conversion with the remaining 75 percent funded with RAD vouchers. As discussed previously, NYCHA has also received HUD waivers to convert its remaining unfunded units to project-based Section 8 funding, which offer a similar level of funding as TPV vouchers.7

The ability to mix RAD vouchers with TPVs and Section 8 vouchers benefits NYCHA in two ways. First, since TPVs and project-based Section 8 units offer a higher per-unit rent subsidy than RAD, adding these funding sources into a RAD transaction allows allow NYCHA’s private partners to generate enough income that they can finance renovations with conventional debt and equity. Projects with RAD vouchers alone, such as Ocean Bay, cannot support conventional private debt. The second benefit is that the use of conventional debt allows the City and State to preserve their tax-exempt bonds, tax credits, and public subsidies for other affordable housing projects.

This strategy may not be replicable across NYCHA’s portfolio. NYCHA 2.0 anticipates that NYCHA will increase its use of TPVs over time, but its ability to use TPVs is subject to HUD approval and the availability of funding. NYCHA 2.0 assumes that TPVs would fund the majority of PACT conversions by as soon as 2020, but NYCHA would need to secure HUD approval to increase the share of TPVs used in individual conversion projects beyond the 25 percent share allowed as-of-right.

Because Section 18 dispositions are available only to developments that are functionally obsolete and whose renovation is costly, they are well-suited to NYCHA’s small developments, which have the largest per-unit needs among all properties in NYCHA’s portfolio. In contrast, the capital needs of many larger developments fall short of the Section 18 cost threshold. PACT developments that do not meet the standards for Section 18 dispositions need to rely solely on RAD subsidies, which do not generate enough income to support conventional private loans.

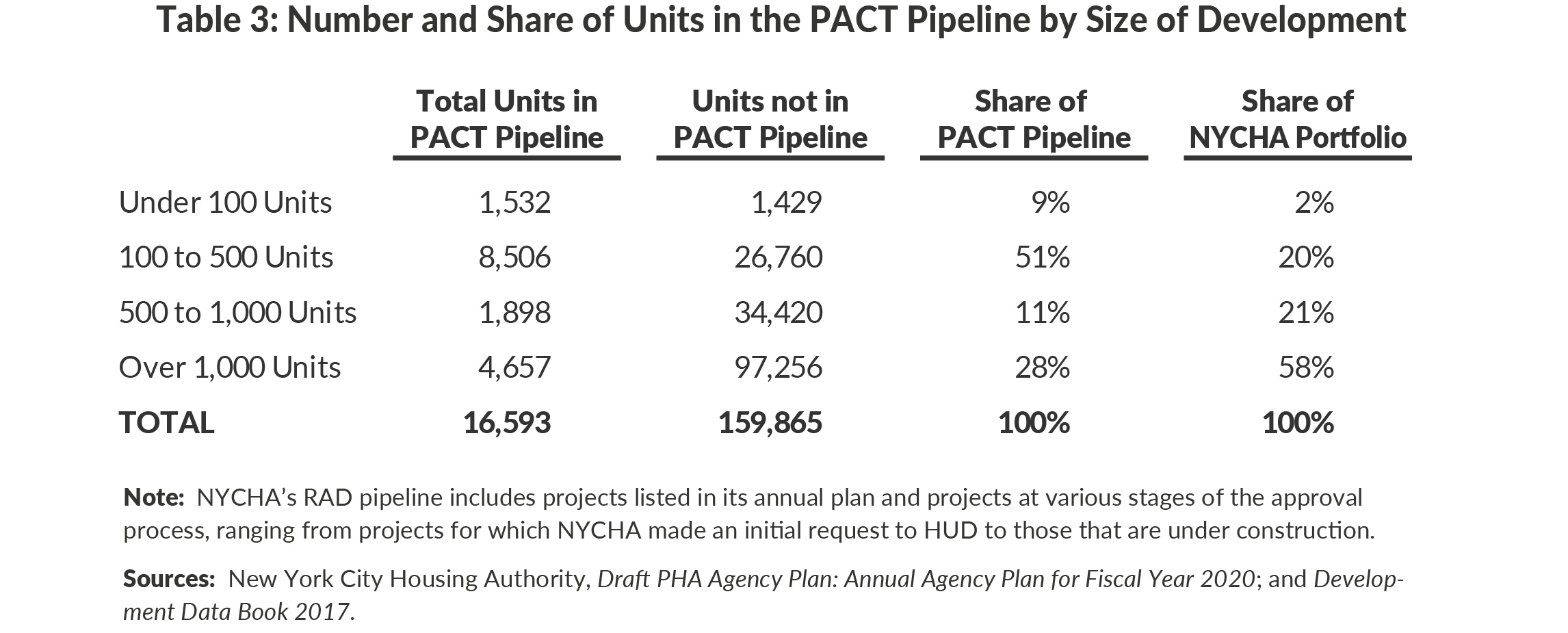

Given these funding limitations, NYCHA’s PACT conversions have focused primarily on smaller developments. More than 60 percent of NYCHA’s PACT pipeline consists of developments with 500 or fewer units, even though they make up just 22 percent of NYCHA’s portfolio. In contrast, developments with 500 or more units make up 78 percent of NYCHA’s portfolio but just 40 percent of the PACT pipeline. Of the developments with 500 or more units currently in the pipeline, four (Independence Towers, Williams Plaza, Boulevard, and Linden) are federally-unfunded developments that have secured project-based Section 8 vouchers. Only two federally funded developments with more than 500 units (Williamsburg Houses and Harlem River Houses) are currently in the pipeline, and NYCHA has not yet issued RFPs for these. NYCHA’s ability to convert additional properties beyond its current pipeline will require additional financial support from the City and State, as well federal actions to make it easier to finance RAD conversions.

NYCHA will need to rely on additional funding sources to accelerate the pace of its RAD conversions. CBC recommended the City allocate more of its robust capital budget for affordable housing to NYCHA to accelerate repairs and the ability to complete RAD deals. The City has increased planned capital funding for NYCHA to $2.5 billion through 2023, including $1.2 billion in funding committed pursuant to the HUD agreement, but none of this funding has gone to support RAD conversions. The City pledged to create a new “public housing recapitalization” division at HDC to help NYCHA finance PACT conversions and to oversee asset management and loan compliance. In November 2018 HDC originated a construction loan funded by its corporate reserves for the renovation of the Baychester and Murphy Houses and will also fund a permanent loan for the project upon its completion.

Another possible source of additional financing for RAD conversions is private activity bonds. In 2019 the federal government authorized New York State to issue up to $2.1 billion in tax-exempt private activity bonds for affordable housing and other uses that are capped under federal law, commonly referred to as “volume cap.” Historically New York City and State have used nearly all of the volume cap for the preservation or construction of affordable housing. New York State typically allocates one-third of this to New York City, with the Dormitory Authority and the Division of the Budget allocating the remaining two-thirds, some of which also is allocated to New York City projects.8

In May 2019 HDC’s board approved a Declaration of Intent for the Brooklyn “mega-bundle,” a package of 2,625 scatter-site and unfunded units in Brooklyn, which will allow HDC to issue up to $497 million in tax-exempt private activity bonds in the future. HDC will need to pass an additional resolution before the bonds are issued.9 Funding NYCHA’s PACT pipeline with private activity bonds, however, would require the City and State devote a substantial share of their volume cap to NYCHA for the long run.

Build to Preserve

NYCHA controls 80 million square feet of unused development rights. NYCHA plans to monetize the value by partnering with private developers to construct new buildings on vacant or underutilized land on NYCHA campuses. (CBC’s infographic explains how infill development provides resources to NYCHA, and how the amount of revenue generated by infill projects varies greatly depending on a project’s location and its share of market-rate units.)

In line with CBC’s recommendations, NYCHA 2.0’s goal is to use infill development to provide $2 billion of capital funding over 10 years by accelerating the pace of infill projects and by increasing the share of market-rate units to 70 percent, consistent with the City’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing program.

NYCHA’s market-rate infill projects have stalled since the release of NYCHA 2.0 in part due to resistance from elected officials and concerns from residents, and no new requests for proposals have been issued. NYCHA withdrew plans for a planned 50-50 project at Holmes Towers in the Upper East Side following a lawsuit filed by Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, though the authority plans to propose a revised project at Holmes Towers with a larger share of market-rate units.10 This change would likely generate more resources for NYCHA, but the new plan may face similar opposition. Mixed-income infill proposals at Cooper Park, Wyckoff Gardens, and LaGuardia also appear stalled.11 Another proposal for an infill building with 75 percent market rate units at Harborview Terrace was postponed.12 These delays have deprived NYCHA of revenue that could have funded repair work and will make it difficult to achieve the $2 billion goal.

One promising happening is NYCHA’s proposal to use infill development as part of the phased redevelopment of the Fulton Houses in Chelsea. Through a combination of infill development and RAD, NYCHA has proposed to partner with a private developer to build new units on vacant land, relocate current tenants to the new building, demolish the vacated buildings, and replace them with additional new housing. The project would allow NYCHA to preserve its deeply affordable housing stock, improve tenants’ quality of life, and add additional affordable units without displacing current residents.

While phased redevelopment was not included in NYCHA 2.0, NYCHA subsequently began discussions with tenants at Chelsea’s Fulton Houses about pursuing a RAD conversion that incorporates infill development and the demolition of two low-rise buildings home to 72 of Fulton’s 944 units. Tenants of the demolished buildings would move into units in a newly-constructed building on the grounds of the Fulton Houses before demolition proceeded. Proceeds from the new infill buildings would then fund a significant share of the cost of renovating the remaining 872 units. No tenants would be required to move off campus, and the entire campus would be renovated and upgraded. The proposal is still in its initial phases, and NYCHA has not yet begun the process of requesting HUD approvals. NYCHA expects to issue an RFP for the Fulton Houses project this fall.13

Despite NYCHA and the City’s substantial outreach to tenants, however, a number of elected officials have attempted to delay the project by requesting additional meetings and outreach beyond NYCHA’s existing efforts.14 The Fulton Houses infill project would raise tens of millions of dollars towards addressing Fulton Houses’ $168 million in capital needs. The repairs funded by the infill proceeds would allow NYCHA to improve the quality of life of the more than 2,000 residents who live at Fulton Houses without displacement or sacrificing public control. Delaying the project without presenting an alternative to address its substantial needs will deprive tenants of long-overdue upgrades. Blocking the revenue-raising infill project also means that the cost of repairing Fulton Houses will come from a limited pool of public subsidies that could have been used at other NYCHA developments if the infill project had gone forward.

Transfer to Preserve

NYCHA 2.0 plans to raise $1 billion through the transfer of development rights to adjacent properties. NYCHA has identified at least four initial air rights sales opportunities. Two have the potential to raise revenue for the authority: the sale of 90,634 square feet from the Ingersoll Houses in Fort Greene, Brooklyn for a new residential building, and the sale of 30,000 square feet from the Fulton Houses in Chelsea for a commercial office project.15 NYCHA expects to raise $25 million from the Ingersoll sale, with 100 percent of proceeds funding repairs at Ingersoll Houses.16 No public estimate of Fulton Houses development rights is available, but air rights could raise $7.5 million if they sell for $250 per square foot.17 NYCHA also has received proposals to transfer 27,000 square feet from developments in Queens and Brooklyn for 100 percent affordable housing developments. These projects will raise less than $1 million combined but would yield additional affordable housing units.18

While NYCHA has started engaging interested developers, the projects currently under consideration would achieve less than 5 percent of NYCHA’s goal. NYCHA plans to issue a formal Request for Expressions of Interest (RFEI) for potential air rights sales; responses to this RFEI will help determine the prospects of reaching its $1 billion goal.

Fix to Preserve Initiatives

Fix to Preserve initiatives have started to move forward, but with less momentum than Invest to Preserve, and are likely to be replaced as NYCHA establishes action plans and a reorganization strategy under the guidance of the federal monitor and management consultants.

While NYCHA launched some initiatives including maintenance blitzes and rapid response teams in January, its work order backlog continues to grow. Open work orders increased 24 percent between the release of NYCHA 2.0 in December 2018 and July 31, 2019, and the average time to complete repairs increased from 71 days to 112 days.19 Drawing conclusions from the data is challenging since changes may be attributable to improved accuracy of NYCHA reporting on closed work orders, as well as a flurry of new work orders generated by additional inspections for lead, mold, and other issues.

Meaningful progress towards reaching a state of good repair will require fundamental shifts in property management practices, work rules, schedules, job responsibilities, and contracting. NYCHA cannot achieve these changes without the cooperation of labor, state and local lawmakers, and federal officials, who have varied widely in their support and cooperation.

Achieving efficient and effective property management requires collective bargaining reforms. (See CBC reports Room to Breathe and Cleaning House for more details on how NYCHA’s cost of operations are out of line with private sector standards.) NYCHA took an initial step in a recent collective bargaining agreement with Teamsters Local 237, the bargaining unit representing caretakers and heating plant technicians. As part of the agreement, the union agreed to new alternative work schedules with shifts on mornings, evenings, and weekends. The alternative work schedules for caretakers launched in April 2019 at 13 developments and will expand citywide by 2020.

This agreement was important because NYCHA’s high labor costs, driven in part by limited schedules, onerous work rules, and outdated job titles, contribute to its high per-unit operating costs.20 The City agreed to cover the cost of wage increases resulting from the new collective bargaining agreement with the caretakers, as it has done with similar agreements for NYCHA’s unions during the de Blasio Administration.21 The City’s Adopted Budget for Fiscal Year 2020 includes $101 million in fiscal year 2020 for collective bargaining-related costs for NYCHA.22 The alternative work schedules may help improve conditions for tenants, but they come at a high price, and one that not be sustainable if the City does not continue to subsidize NYCHA’s labor costs.

NYC Operating Support for NYCHA

NYCHA’s operating budget would not be balanced without funding from New York City. The Authority’s 2019 operating budget projects a $33 million surplus, but relies on $288 million in City funds. In the future, NYCHA projects budget gaps despite substantial continued City support. Relying on City funding makes NYCHA vulnerable should the City’s financial position weaken during an economic downturn or if political priorities change under a future administration.

Another vulnerability is that NYCHA has not yet expanded alternative work schedules to other bargaining units. NYCHA reached a similar agreement with its maintenance workers union, but the local’s membership rejected the deal. NYCHA and its maintenance workers are currently in arbitration.22 NYCHA has not made progress with skilled trades, who play a critical role in addressing the work order backlog and represent a disproportionate share of the housing authority’s overtime budget.23

Additional Developments that Affect Implementation of NYCHA 2.0

Delays in Securing State Funding for NYCHA

NYCHA 2.0 assumes the State will provide $450 million in capital funding that was appropriated in 2016 and 2017 but has not yet been released to NYCHA. After previously issuing an executive order that made the funding contingent upon the appointment of an emergency manager, Governor Cuomo pledged in February 2019 to release the funding following the appointment of NYCHA’s federal monitor.25 Later that month, he said it would be released following passage of the state budget.26 In April the Governor's spokesperson said that NYCHA’s slowness in identifying projects was the source of delays, even though NYCHA officials claimed they submitted a revised list of projects to state officials.27 In early September state budget officials said that they reached an agreement with NYCHA to release the funding following the approval of the federal monitor, though the monitor has not received the final agreement.28 Assuming that NYCHA is able to enter into construction contracts for the state-funded projects in 2020, these delays will have cost NYCHA tens of millions of dollars in value due to inflation compared to what the funding would have purchased if it had been released in 2017.

The Legislature approved an additional $100 million for lead remediation and abatement in June 2019.

Design-Build and Alternative Project Delivery Strategies

In June 2019 the Legislature passed a bill authorizing NYCHA and some City agencies to use design-build and some forms of construction manager-at-risk for capital projects funded by the City or State, if the work is performed under the auspices of a project-labor agreement and does not displace unionized NYCHA employees.29 The bill has not yet been delivered to the Governor to sign.

Approving this bill would allow NYCHA to complete some capital projects faster and for less money; however, the benefits of design-build will be limited by certain mandates included in the bill. For example, a non-displacement clause will limit NYCHA’s ability to enter into private service contracts to maintain new heating plants and elevators built through design-build and funded by the City or State. NYCHA has increasingly entered into these agreements when repairing or upgrading equipment. Last fall, NYCHA announced that it would outsource the management of heating plants at 41 developments.30 CBC has supported NYCHA’s efforts to increase the use of private service and job order contracts in order to reduce overtime, improve the deployment of existing skilled trade staffers, and contribute to improved conditions for residents. For some projects, the bill will force NYCHA to choose between saving money on construction by using design-build but spending more on maintenance or spending more upfront by using traditional procurement in order to realize efficiencies by using private maintenance contractors.

Federal law still prohibits the use of these alternative methods for federally funded capital projects (which are the bulk of the 2019 to 2023 capital plan).31

Continued Lack of New Federal Regulatory Relief or Funding

NYCHA’s settlement with federal prosecutors and HUD did not include any additional federal funding or regulatory relief to help NYCHA address the issues raised in the complaint, even though federal underfunding and restrictive federal regulations were responsible in part for NYCHA’s capital crisis.

NYCHA’s federal monitor should work with the new Chair to identify changes to federal laws and regulations that would support NYCHA’s turnaround efforts. These changes could include: increasing funding for federal operating and capital subsidies; improving RAD by lifting the cap on conversions, exempting RAD conversions from the tax-exempt private activity bond cap, or creating dedicated tax credits for the RAD program; lifting the federal prohibition on design-build and best value procurement for federally-funded capital projects; additional appropriations for tenant protection vouchers; and allowing for more flexible use of federal capital and operating dollars, in part to allow NYCHA to reinvest operating savings into capital upgrades.

Conclusion

Since the release of NYCHA 2.0, NYCHA has made halting progress towards implementing its turnaround plan, but future prospects are shaky. While the Authority is increasing the number of units in its PACT pipeline, funding restrictions and federal laws may limit its ability to realize its ambitious goal. Proposals to raise funding through the sale of air rights are proceeding, but proposals for market-rate infill development appear to have stalled in the face of opposition from some public officials and community groups. NYCHA has also launched weekend work blitzes to address long-standing work order backlogs and address critical health and safety issues, but its efforts to modernize work schedules through collective bargaining have yet to address long-standing productivity issues or contain the growth of its operating budget.

The costs of the delays are significant. NYCHA 2.0 would raise $16 billion in new revenue for capital repairs over 10 years; given an average per-unit capital need of $181,000, that is enough funding to repair more than 8,700 units annually. If half of NYCHA 2.0 funding is not secured, over 4,000 units each year would not be renovated, and the cost to repair them will continue to rise.

The ultimate success of NYCHA 2.0, along with any future turnaround plans, will require political and community support; assistance from the City, State, and federal governments; and significant management improvement. Based on the results and factors affecting the early implementation of NYCHA 2.0, the chance of success is far from guaranteed.

Download Report

NYCHA 2.0: Progress at RiskFootnotes

- Agreement of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the New York City Housing Authority, and the City of New York, January 31, 2019, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/PA/documents/HUD-NYCHA-Agreement013119.pdf.

- Sean Campion, “Stabilizing the Foundation” (Citizens Budget Commission, July 2018), https://cbcny.org/research/stabilizing-foundation.

- HUD gave NYCHA approval in 2008 to convert 8,400 of the unfunded units to Section 8 upon vacancy– 4,078 of those have converted as of April 2019. NYCHA got another waiver in 2018 to convert 4,000 units immediately rather than on vacancy, with the goal of including those properties in PACT megabundles. For more information on these units, see: Sean Campion, “Room to Breathe: Federal and City Actions Help NYCHA Close Operating Gaps, But More Progress Needed on Implementing NextGenNYCHA” (Citizens Budget Commission, July 2017), https://cbcny.org/research/room-breathe.

- New York City Housing Authority, Draft PHA Agency Plan: Annual Agency Plan for Fiscal Year 2020 (May 31, 2019), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/nycha/downloads/pdf/FY%202020%20Draft%20Annual%20Plan%20and%20Five-Year%20Agency%20Plan.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Properties Participating in RAD Program,” RAD Resource Desk (accessed September 6, 2019), http://www.radresource.net/pha_data.cfm.

- The lone exception was the Ocean Bay development, which is NYCHA’s only RAD transaction to date that has used tax-exempt bonds. The total cost of rehabilitating the 1,395-unit Ocean Bay development was $318 million, but NYCHA was only able to obtain $213 million in tax-exempt bonds backed by the value of RAD subsidies. To make the project financially feasible, NYCHA used $105 million in Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) funding that was available to repair damage that Ocean Bay sustained during Superstorm Sandy.

- NYCHA also received permission from HUD in 2008 to convert 8,400 of its 20,170 unfunded units to project-based Section 8 vouchers. Under the plan, NYCHA has been converting unfunded units to Section 8 as units become vacant. As of April 2019, NYCHA had converted 4,078 of the initial 8,400 units to Section 8. In September 2018, NYCHA received permission from HUD to convert 3,581 of the remaining units with the current tenants in place rather than waiting to convert them upon vacancy. Source: New York City Housing Authority, Draft PHA Agency Plan: Annual Agency Plan for Fiscal Year 2020 (May 31, 2019), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/nycha/downloads/pdf/FY%202020%20Draft%20Annual%20Plan%20and%20Five-Year%20Agency%20Plan.pdf.

- Daniel L. Parcerisas and Ilene Popkin, Pump up the Volume: Recommendations to Improve the Allocation of Private Activity Bonds to Better Support Housing in New York State” (Citizens Housing and Planning Council, December 2014), http://chpcny.org/assets/2_19-Pump-up-the-Volume-FINAL.pdf.

- New York City Housing Development Corporation, “Resolution of Declaration of Intent of the New York City Housing Development Corporation: Brooklyn Megabundle” (May 30, 2019), http://www.nychdc.com/content/pdf/BoardMaterial/053019/DOI-Brooklyn%20Megabundle.pdf.

- Rachel Holliday Smith, “Brewer Ups Legal Fight Against Private Tower at NYCHA Site,” The City (June 25, 2019), https://thecity.nyc/2019/06/gale-brewer-ups-legal-fight-against-tower-at-nycha-site.html.

- Sally Goldenberg, “City quietly pauses plans for private development at NYCHA site,” Politico New York (May 6, 2019), https://www.politico.com/states/new-york/city-hall/story/2019/05/05/city-quietly-pauses-plans-for-private-development-at-brooklyn-nycha-site-1007308.

- Rachel Holliday Smith, “Long-Delayed Development at Hell’s Kitchen NYCHA Site Pulled After 14 Years,” The City (April 16, 2019), https://thecity.nyc/2019/04/nycha-pulls-harborview-development-plans-after-14-years.html.

- Sally Goldenberg, “Political fight threatens de Blasio's plans to remake public housing complex in Manhattan,” Politico New York (September 12, 2019), https://www.politico.com/states/new-york/city-hall/story/2019/09/11/political-fight-threatens-de-blasios-plans-to-remake-public-housing-complex-in-manhattan-1185275.

- Rep. Jerrold Nadler, Member of Congress, et. al, to Vicki Been, Deputy Mayor for Housing and Economic Development, City of New York, and Gregory Russ, Chair and Chief Executive Officer, New York City Housing Authority (letter, September 12, 2019), https://nadler.house.gov/uploadedfiles/2019.9.12_fulton_houses_working_group_follow_up_final.pdf.

- New York City Housing Authority, Draft PHA Agency Plan: Annual Agency Plan for Fiscal Year 2020 (May 31, 2019), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/nycha/downloads/pdf/FY%202020%20Draft%20Annual%20Plan%20and%20Five-Year%20Agency%20Plan.pdf.

- Joe Anuta, “NYCHA moves on first air rights sale in sweeping reform plan,” Politico New York (July 31, 2019), https://subscriber.politicopro.com/article/2019/07/31/nycha-moves-on-first-air-rights-sale-in-sweeping-reform-plan-1124251.

- The price of $250 per square foot is based on CBC’s previous analysis of the value of NYCHA’s transferrable development rights. See: Sean Campion, “Stabilizing the Foundation” (Citizens Budget Commission, July 2018), https://cbcny.org/research/stabilizing-foundation.

- New York City Housing Authority, Draft PHA Agency Plan: Annual Agency Plan for Fiscal Year 2020 (May 31, 2019), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/nycha/downloads/pdf/FY%202020%20Draft%20Annual%20Plan%20and%20Five-Year%20Agency%20Plan.pdf.

- New York City Housing Authority, NYCHA Metrics: Open Work Orders (accessed August 19, 2019), https://eapps.nycha.info/NychaMetrics/Charts/PublicHousingChartsTabs/?section=public_housing&tab=tab_repairs.

- CBC previously found that NYCHA’s costs were 39 percent higher than the cost to operate the average rent-stabilized unit, excluding property taxes, and that public housing residents report substantially two to three times as many building deficiencies as tenants in privately-owned rental housing. See: Sean Campion, “Stabilizing the Foundation” (Citizens Budget Commission, July 2018), https://cbcny.org/research/stabilizing-foundation.

- On top of receiving raises and increased annuity contributions, caretakers opting into one of the new alternative work schedules will receive a one-time $1,500 bonus for signing up for an alternative work schedule. In addition, all caretakers working an alternative schedule will receive a 20 percent hourly premium for work on a Saturday or Sunday as part of their regular workweek, with the premium included for calculating overtime and benefits and longer break periods. All hours in excess of the standard work day or the standard work week will be paid at time and a half except for non-scheduled Sunday work, which is paid at time and three quarters. The agreement anticipates that 75 percent of caretakers will be on one of the alternative schedules. Some of these additional costs will be offset by health care savings and the reduced need to schedule evening and weekend overtime shifts. These savings will allow NYCHA to hire additional caretakers. See: City Employees Local 237, IBT/New York City Housing Authority Memorandum of Agreement (December 12, 2018), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/olr/downloads/pdf/collectivebargaining/local-237-nycha-moa-2018-2021.pdf.

- City of New York, Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget, Adopted Budget Fiscal Year 2020, Supporting Schedules (June 2019), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/ss6-19.pdf.

- Richard Steier, “Local 237 Maintenance Workers Veto Pay Deal that Extended Hours at HA,” The Chief Leader (May 13, 2019), https://thechiefleader.com/news/news_of_the_week/local-maintenance-workers-veto-pay-deal-that-extended-hours-at/article_c3024470-7340-11e9-9c59-b77362705b8f.html.

- CBC has offered options for how NYCHA can clear the work order backlog while also reducing overtime spending by modernizing work rules and schedules for the skilled trades and increasing the use of contractors to supplement the in-house workforce. See: Sean Campion, “Stabilizing the Foundation” (Citizens Budget Commission, July 2018), https://cbcny.org/research/stabilizing-foundation.

- Courtney Gross, “Cuomo May Finally Deliver $450M He Promised to NYCHA,” NY1 (February 4, 2019), https://www.ny1.com/nyc/all-boroughs/politics/2019/02/05/andrew-cuomo-may-finally-deliver-450-million-dollars-he-promised-to-nycha.

- Josefa Velasquez and Greg B. Smith, “Cuomo Ready to Deliver on Long-Delayed NYCHA Aid, Says Monitor,” The City (April 10, 2019), https://thecity.nyc/2019/04/cuomo-ready-to-deliver-on-delayed-usd450m-in-nycha-aid.html.

- Sally Goldenberg, “State still holding onto $450M in NYCHA Funding,” Politico New York (April 2, 2019), https://subscriber.politicopro.com/article/2019/04/01/state-still-holding-onto-450m-in-nycha-funding-945402.

- Courtney Gross, “State Says Agreement Reached on $450 Million in Funds to NYCHA,” NY1 (September 4, 2019), https://www.ny1.com/nyc/all-boroughs/news/2019/09/05/states-says-agreement-reached-on--450-million-in-funds-to-nycha.

- New York State Assembly, A7636B (2019-2020 Session), https://nyassembly.gov/leg/?bn=A07636&term=2019.

- Gloria Pazmino and Sally Goldenberg, “Private contractors step in as NYCHA’s heating season begins,” Politico New York (October 18, 2018), https://www.politico.com/states/new-york/albany/story/2018/10/18/costing-millions-private-contractors-step-in-as-nychas-heating-season-begins-657080.

- NYCHA’s $6.4 billion capital plan for 2019 to 2023 assumes $3.1 billion in federal funding, including $2.1 billion in public housing capital subsidies, $825 million in disaster relief funding, and $206 million in Community Development Block Grants. See: New York City Housing Authority, Capital Plan Calendar Years 2019-2023 (December 19, 2018), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/nycha/downloads/pdf/capital-plan-narrative-2019.pdf.