Accounting (and More) for a Better Budget

Strategies to Improve New York State Budgeting and Fiscal Management

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The New York State budget identifies the funds to be received from taxes, fees, federal and other sources and allocates more than $220 billion to be spent on education, health care, criminal justice, transportation, and all other operations and capital investments of the State. New Yorkers should be able to count on their elected leaders to make sound decisions that efficiently and effectively use the people’s resources to deliver vital services and supports.

Today, though, the State’s budgeting and fiscal management processes have many shortcomings:

- Existing laws, rules, and common budgeting and reporting practices limit the State’s ability to make sound fiscal decisions. Reliance on the cash basis of accounting and budgeting allows the State to obfuscate actual spending trends and budget balance. Caps on the Rainy Day Fund are too restrictive and prevent the State from saving adequately for a fiscal emergency. Caps on State debt, on the other hand, are too easily subverted

- The State’s budgeting also is opaque and limits public and legislative review of fiscal decisions as they are being made. Some budget bills and other legislation are not accompanied by fiscal estimates of their expected impact. Budget bills are also often voted on quickly, curtailing the opportunity for meaningful review by the public and legislators

- Existing budget monitors, such as the Comptroller and the Authorities Budget Office, have seen their authority and power reduced over time, precluding comprehensive oversight of the budget, State agencies and authorities, and fiscal management. New York State also lacks an independent budget office to provide nonpartisan, independent oversight and analysis of the budget and fiscal decisions

- Budget and fiscal management decisions are not informed by a comprehensive public performance measurement and management system. New York State’s lack of a system to publicly measure progress toward goals not only hampers quality operational management, but it also leads to a lack of information to make evidence-based decisions during budget deliberations and implementation.

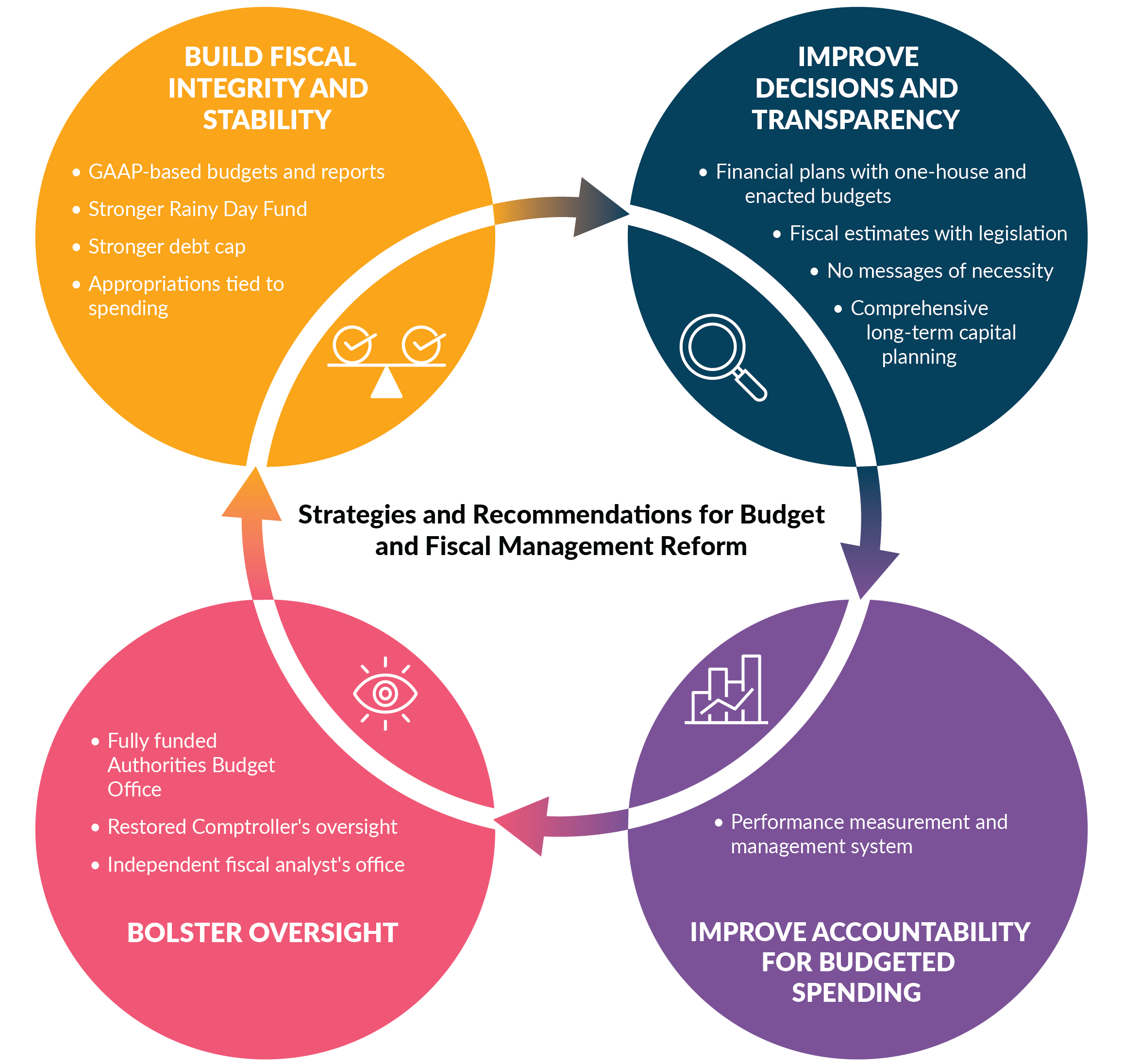

This report analyzes the existing State fiscal processes, identifying problems throughout the planning, negotiation, and implementation of the budget. It presents four strategies to rectify these problems and improve the State’s budgeting and fiscal management, and makes 12 specific recommendations to achieve these strategies. CBC recommends the State:

I. Increase fiscal integrity and stability by standardizing accounting, building reserves, strengthening debt management, and eliminating illusory appropriations.

- Manage, report, and balance the budget in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles on a modified accrual basis.

- Strengthen the Rainy Day Fund by raising deposit and balance caps, combining all reserve funds, and mandating deposits when revenues are strong.

- Strengthen the debt cap.

- Tightly tie appropriations to planned spending by reducing unfunded and undefined spending authority.

II. Improve budget decisions by generating, publishing, and ensuring adequate time to use critical decision-relevant information.

- Require financial plans with budget bills.

- Require fiscal estimates with other legislation.

- Prevent the use of messages of necessity for budget bills.

- Implement comprehensive, transparent long-term capital planning processes.

III. Bolster oversight and accountability by appropriately strengthening fiscal monitors.

- Fully fund the Authorities Budget Office.

- Establish an independent fiscal analyst's office.

- Restore Comptroller's oversight of procurement and contracting.

IV. Improve accountability for budgeted spending.

- Implement a performance measurement and management system.

This is an opportune time for fiscal reform. The State learned new lessons from the fiscal shocks, especially those caused by the pandemic, such as the importance of adequate fiscal reserves and fiscal oversight. Furthermore, the memory of the pre-pandemic Medicaid payment delay that obfuscated the budget so significantly that it masked a near-crisis budget overrun is still fresh enough in the public’s mind. The first year in the Governor’s first full term provides an opportunity to tackle issues that may not generate attention in an election, but would improve the State’s transparency, culture, and core functions, especially regarding the budget. These improvements can build on recent progress bolstering the Rainy Day Fund, increasing funding to the Authorities Budget Office, enacting legislation (awaiting the Governor’s signature) to restore Comptroller oversight, and delivering more fiscal reports on time. Still, there is much more that can and should be done.

Immediate Actions

While some of these recommendations may be controversial or require significant changes to management and budgeting systems, others can and should be implemented immediately. Specifically, to improve the basis for budget decisions, oversight, accuracy of appropriations, the State should:

- Include basic financial plan tables with one-house budgets;

- Publish basic financial plan tables when the budget is enacted;

- Include complete fiscal impact statements with all relevant bills;

- Avoid using messages of necessity for budget bills;

- Increase funding to the Authorities Budget Office;

- Restore procurement oversight to the Comptroller;

- Exclude unfunded appropriations; and

- Avoid lump sum appropriations.

Conclusion

These recommendations—many of which are drawn from budget reform proposals from fiscal policy experts over the past 25 years—would help the State’s elected leaders enact stronger budgets with greater oversight and transparency. It is critically important that the State’s budget and fiscal management processes be improved to enable better decision-making, outcomes, and accountability.

INTRODUCTION

The New York State budget directs the collection and spending of more than $220 billion annually. New York levies some of the highest taxes in the nation and spends those tax and other receipts on an expansive portfolio of programs to serve New Yorkers—supporting health care coverage for 8.5 million people, educating 2.6 million K-12 students and 400,000 State university students, and funding other programs ranging from environmental protection to social supports to employment and more.

To know how their resources are being spent, New Yorkers deserve timely budget and fiscal management processes that raise, allocate, and report on public funds based on sound information and in a transparent manner. However, the existing processes are too often mired in imprudent fiscal decisions, insufficient information, inadequate long-term planning, diminished oversight, and impediments to management.

CBC identified four overarching problems in the current processes:

- Fiscal management systems that allow gimmickry that masks the fiscal condition and impedes sound decisions;

- Insufficient time and information to make decisions;

- Insufficient or absent fiscal oversight; and

- Fiscal decisions and management that lack a long-term focus and basis in evidence.

This report presents four strategies to address these problems and makes 12 specific recommendations to achieve those strategies. This framework will improve the soundness, transparency, oversight, and accountability of the State’s fiscal management and budget processes:

I. Increase fiscal integrity and stability by standardizing accounting, building reserves, strengthening debt management, and eliminating illusory appropriations.

- Manage, report, and balance the budget on a modified accrual basis in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).

- Strengthen the Rainy Day Fund by raising deposit and balance caps, combining all reserve funds, and mandating deposits when revenues are strong.

- Strengthen the debt cap.

- Tightly tie appropriations to planned spending by reducing unfunded and undefined spending authority.

II. Improve budget decisions by generating, publishing, and ensuring adequate time to use critical decision-relevant information.

- Require financial plans with budget bills.

- Require fiscal estimates with other legislation.

- Prevent the use of messages of necessity for budget bills.

- Implement comprehensive, transparent long-term capital planning processes.

III. Bolster oversight and accountability by appropriately strengthening fiscal monitors.

- Fully fund the Authorities Budget Office.

- Establish an independent fiscal analyst's office.

- Restore Comptroller's oversight.

IV. Improve accountability for budgeted spending.

- Implement a performance measurement and management system.

This report’s first section describes and identifies the problems with the State’s existing budget and fiscal management processes. The second section identifies the four strategies to address these problems and details the 12 recommended policy and management actions to achieve those strategies.

THE STATE’S BUDGET AND FISCAL MANAGEMENT PROCESSES

The State’s fiscal processes are guided primarily the State Constitution, State Finance Law, and common practices and precedents. Article VII of the Constitution outlines the general budget timeline and the budgetary roles of the Governor, Legislature, and Comptroller. State Finance Law specifies details about the budget process, including information required in fiscal reports. Common practices and government’s cultural precedents also play a major role, forming de facto rules for how the budget is developed and enacted.

The Constitution and State Finance Law place guardrails on key budget decisions, including:

- The proposed and enacted General Fund budgets must be balanced, defined as the level of receipts is greater than or equal to disbursements;

- The annual deposits to and the total balance of the State’s Rainy Day reserves are capped and withdrawals conditioned; and

- The levels of outstanding debt and annual debt service are capped.

The Executive Budget

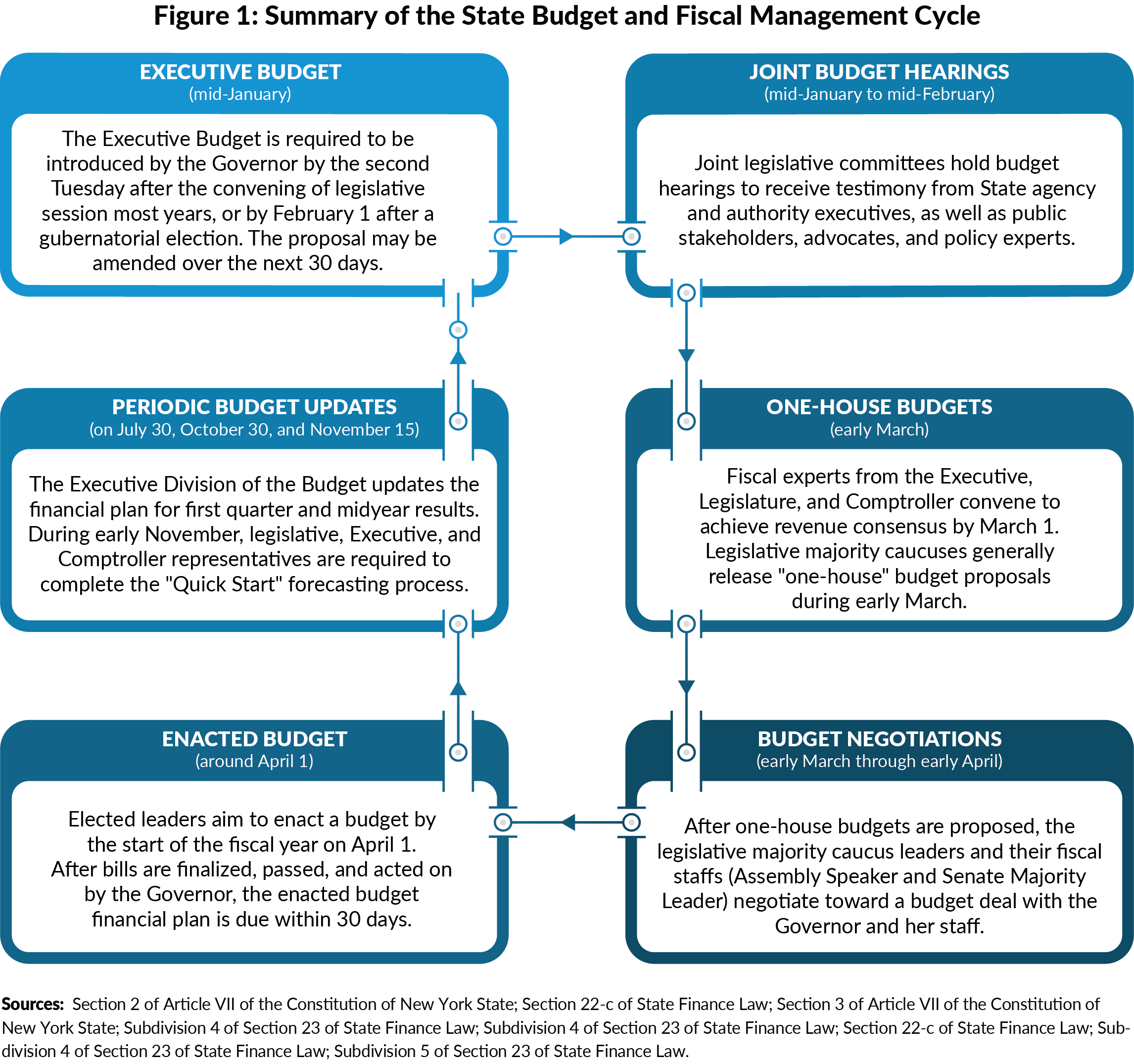

The State’s budget process is started and led by the Executive branch—the Governor and State agencies and authorities.1 After months of preparation by the Governor’s office and agencies, the budget cycle begins with the Governor's Executive Budget proposed by the second Tuesday after the convening of the legislative session each year (or by February 1 in years following a gubernatorial election).2 The Governor is empowered to make amendments to the Executive Budget over the next 30 days.3 The amendments are generally minor technical changes but may include major fiscal and policy changes.

The Executive Budget is comprised of budget bills and the supporting documents. There are two types of budget bills: appropriations bills that authorize spending and “Article VII bills,” named in reference to the relevant section of the Constitution, that contain the associated statutory changes governing programs and operations.4 Appropriations bills provide the legal authority to spend, through new appropriations and through re-appropriations that re-authorize authority passed in previous budgets. While the organization of budget bills is not legally mandated, there commonly are five appropriations bills (grouped by the type of spending they support) and five Article VII bills (grouped by subject matter areas).

Key supporting documents include the Financial Plan and the Capital Program prepared by the Governor’s Division of the Budget (DOB). The Financial Plan describes budget actions and reports fiscal projections for the budget year and at least three subsequent years (“out-years”). The Capital Program is similar to the Financial Plan but provides greater detail on capital spending and includes projections for an additional out-year.5

The Financial Plan provides critical information that is essential for analyzing the budget and assessing the State’s fiscal condition. Whereas the budget bills are negotiated and voted on by the Legislature and provide the legal authority to spend and define program parameters, only the Financial Plan, which is prepared by the Executive, presents the budget’s planned total and detailed receipts and disbursements in tabular form. It shows actual budget results for the prior year; the current year budget; the upcoming year’s receipts, disbursements, and net results, including whether the budget for the upcoming year is balanced as required by law; and the spending, receipts, and reserves in the three following years. It shows planned transfers between various State accounts and the use of State and federal resources to support programs and operations.

Budget Hearings, Revenue Consensus, and Negotiation

After the Governor proposes the Executive Budget, the Legislature holds public hearings to receive testimony from State agency and authority heads, and from external stakeholders and experts. These hearings are held jointly by both houses of the Legislature and usually begin about one week after the Executive Budget and conclude within one month. During this stage, the executive and legislative leaders and staff meet primarily to exchange information rather than to negotiate provisions. Legislative analysts for each conference summarize the Executive Budget in briefing books for legislators and the public.6

State law requires the Governor and legislative leaders to meet and agree to how much revenue will be available to spend under current law, a process called “revenue consensus.” If consensus is not reached by March 1, the Comptroller is required to unilaterally establish the revenue figure.

Shortly thereafter, the legislative leaders introduce their own budget proposals, referred to as “one- house” budgets. The one-house budgets are re-introduced versions of the Governor’s budget bills, with the Legislature accepting, rejecting, or modifying Executive Budget provisions. They typically are accompanied by a resolution that describes the components of the one-house proposals. One- house budget resolutions are similar to a Financial Plan since they include narrative descriptions and fiscal estimates of policy proposals. However, they lack many of the Financial Plan’s details, including a tabular presentation of the proposal’s full receipts, disbursements, and net results for the coming and subsequent years, and are not subject to budget balance requirements.

By early March, legislative and Executive Chamber leadership shifts to negotiating the budget, which should be enacted before the start of the fiscal year on April 1. Often, some components are easily negotiated. High-value and sensitive proposals are usually the last to be finalized, either resulting in the relevant bill being delayed, or in sensitive parts being moved from the original bill into one final budget bill to be passed containing a broad array of major actions, called the “big ugly.” In recent years, budgets have been finalized around April 1. In the past, however, budget negotiations often dragged into the summer months. Absent a full budget, emergency budget extenders have been enacted to authorize payment of the State workforce and continue vital programs.

Like all bills, budget bills—including those amended to reflect a final budget agreement—are required to “age” for three days before being voted on. This allows for legislators and the public to read and analyze a bill before it is voted on. To vote on a budget bill on March 31, it would need to have been introduced by March 29. Fairly often, budget bills have been agreed to so close to the start of the next fiscal year that they cannot age and be enacted by March 31. In those cases, the Governor may submit a Message of Necessity (MON), a constitutionally authorized action that allows bills to forgo the aging process and be voted on immediately.

Appropriations bills become law when they are passed by the Legislature, but the Governor can veto individual appropriations or re-appropriations within ten days. The Governor signs or vetoes Article VII bills within ten days of them being delivered to the Governor’s desk, following passage in the Legislature. (Like non-budget bills, they will automatically become law if not acted upon within ten days.)7 After the Governor approves or vetoes all bills, DOB is required to release another edition of the Financial Plan within 30 days.

Budget Implementation and Fiscal Management

The last part of the budget cycle is implementation. In this stage, the Governor, State agencies, and State authorities carry out the work funded in the budget and governed by State law. The State carries out capital projects, distributes grants to local governments and private entities, and pays the State workforce. Over the course of the fiscal year, the State will spend over $220 billion on wide-ranging and far-reaching programs and contracts.

Fiscal management is critical to ensure that spending is executed effectively and prudently: programs should be implemented within authorized funding levels, goods and services should be procured efficiently, and revenues and expenditures should be reported regularly to convey the State’s true fiscal condition. Performance management data and accountability processes should be an integral part of running the government; goal-setting and performance data should inform the actions of managers to achieve the State’s aims, conduct core functions and deliver services.

Oversight is an important part of implementation. External actors validate that the Executive is spending budgeted funds in accordance with the law and track the actions of agencies and authorities in carrying out the work of government. In New York, there are two main fiscal monitors. The State Comptroller provides oversight and analysis of the budget and provides review and approvals of major State contracts and spending to ensure their adherence to the budget and State law. The Authorities Budget Office (ABO) oversees hundreds of State authorities that spend and borrow billions of dollars annually by collecting fiscal data and reporting on their activities.

The State is also statutorily required to report regularly on the budget as it is developed and implemented. Financial Plan updates are required to be published within 30 days of the conclusion of each quarter (by July 30 and October 30). Planning for the next budget also starts early, through a process known as “Quick Start.” Under Quick Start, the Governor, legislative leaders, and Comptroller must issue reports by November 5 with their expectations of receipts and spending for the rest of the current year and the next year. They are then required to meet publicly to discuss their reports, and to issue a joint report of their positions by November 15.

Implementation is continuous, overlapping with the start of the next Executive Budget.

HISTORY OF BUDGET REFORM EFFORTS

The State has gone through several iterations of budget reform, including several major changes to budget practices that were implemented, and other proposed reforms that fell short.

Amendments to Article VII of the Constitution in the 1920’s created the Executive-led budget process that has been in place since 1929, when Governor Franklin Roosevelt proposed the first Executive Budget. The Executive Budget process resulted from several years of studies and reforms proposed by prior New York governors, who complained about the fractured process in which legislators put forth piecemeal appropriations and expenditures. The State had lacked a cohesive financial plan, and partial changes to the legislative-led budget and appropriation process had not cured the fundamental problems.

The Executive Budget process also faced its most significant challenges during the late 1990’s and early 2000’s. Two separate lawsuits, Silver v Pataki and Pataki v New York State Assembly, tested the Governor’s powers in the budget process, with the Legislature and Governor arguing about the uses of powers for each branch in writing appropriations. In 2004, the State Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the Governor in both cases. The rulings clarified that the Governor can enact significant statutory changes through budget bills, rejecting the Legislature’s assertion that the Governor was including broad, non-fiscal statutory changes in Article VII bills. The rulings also prevented the Legislature from changing appropriation language proposed by the Governor. The Legislature is restricted to wholly rejecting appropriations proposed by the Governor or adding wholly new appropriations; the Legislature cannot change appropriation amounts or amend the programmatic text attached to appropriations.8

In the early 2000’s, the State enacted debt reform and considered a broad package of budget process reforms. The Debt Reform Act of 2000 placed caps on both the amount of outstanding debt the State could maintain at any time, and on annual debt service costs. The debt and debt service caps aim to ensure the State does not issue levels of debt it cannot support.9

A major set of constitutional reforms was then put before voters in 2005. The most significant change would have clarified and expanded the role of the Legislature in the appropriations process by essentially voiding the Governor’s Executive Budget if it was not enacted by the start of the fiscal year, granting the Legislature more power to rewrite budget bills. Other proposals would have moved up the dates for submission of the Executive Budget and shortened the period for Executive Budget amendments from 30 days to 21 days.10 A separate set of budget reforms was included in a companion bill, to be implemented only if constitutional changes were approved, that would have shifted the start of the fiscal year to May 1 and established an independent budget office.11 The voters rejected the proposed constitutional changes by a 2-to-1 margin, thereby also nullifying the reforms included in the companion bill.12

After voters rejected the proposed changes, the Legislature and newly elected Governor Eliot Spitzer enacted a new set of reforms in January 2007. The reforms aimed to provide greatertransparency about the budget process and updated the Quick Start and revenue consensus processes that accelerate the collaborative revenue forecasting negotiations. The changes also brought off-budget spending—a practice of spending from certain special revenue accounts with funds dedicated to distinct purposes outside of the financial plan—on-budget and extended the State’s cash basis balanced budget requirement to enacted budget bills. (The Constitution requires a balanced Executive Budget.)13 At the time, CBC stated that these changes represented “significant progress…in improving accountability and transparency in the State’s fiscal decision-making.”14 CBC recommended further reforms that would have bolstered the balanced budget requirement, Rainy Day Fund structure, debt caps, and performance reporting.15

The most recent comprehensive budget reform proposals were made in 2009 when the Great Recession upended the State’s financial plan. With persistent budget gaps, cratering tax receipts, and spending pressures jeopardizing the State budget, discussions opened to address the State’s short-term fiscal crisis and to build a better framework for budget-making going forward. Then Lieutenant Governor Richard Ravitch, a fiscal expert, in 2010 developed a plan to weather the immediate fiscal storm through a combination of revenue, spending, and borrowing actions. He simultaneously recommended fundamental fixes to the State’s budget process. These reforms included instituting a balanced budget requirement on a Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP)-compliant modified accrual basis (rather than the cash basis) and creating an independent review board to provide regular assessments of the financial plan, among other things. However, the Governor and Legislature did not advance the structural reform plans.16

Since 2010, most discussions around the State’s budget process have been marginal or targeted policy choices of mixed results. For example, in a step backwards, Comptroller oversight of State contracts and procurements has been eroded, and the State sidestepped its debt cap early in the COVID pandemic. On the positive side, the State recently increased the size of allowable Rainy Day Fund contributions and balances. The persistent problems in the State’s budget and fiscal management processes justify a reconsideration of a set of comprehensive reforms.

PROBLEMS IN THE STATE’S BUDGET-MAKING AND FISCAL MANAGEMENT PROCESSES

The State’s Executive Budget process has been in place for nearly one hundred years, and over time modifications and reforms to that process have strengthened it. Still, fundamental shortcomings exist in the laws and practices that undermine the quality of budget decisions and the State’s fiscal stability, transparency, accountability, and oversight:

- Fiscal management systems allow gimmickry, including shifting timing of payments, moving items off budget, circumventing debt caps, and impeding sufficient savings. Cash basis accounting can obscure true revenues and expenditures, distort trends in year-to- year spending growth, and hide structural budget gaps. The State can move payments and tax refunds across years and carry prior-year budget balances forward in a way that masks budget balance and actual spending trends. This creates an illusion of adherence to budgeted spending and balanced budgets. Furthermore, the State’s debt cap—which is codified in State law rather than the Constitution—is too easily sidestepped. Finally, the structure of the Rainy Day Fund, which has caps on the amount of annual deposits and overall balance, does not allow for sufficient savings.

- Budget decisions are made with insufficient data on fiscal impacts and without sufficient time. Budget proposals and the enacted budget are finalized without a public financial plan, some non-budget bills lack fiscal estimates despite requiring spending, and budget bills are rushed through voting. These practices diminish the ability of legislators to make sound fiscal decisions and constrain the ability of the public and the press to understand and assess those decisions and legislation. The State also does not have a comprehensive long-term capital planning process. Without a comprehensive regular assessment of the condition of capital assets and long-term plans to maintain all in a state of good repair, priorities are not well identified and infrastructure conditions may deteriorate.

- Fiscal oversight is inadequate or absent. In making a sound budget, it is also important that State fiscal monitors are empowered to quickly and fully assess the implications of the State’s fiscal management. The capacities and powers of the Comptroller and ABO have eroded over time, and the State lacks an independent budget office to provide nonpartisan, independent oversight and analysis of the budget and fiscal decisions.

- Fiscal decisions lack a long-term focus and basis in evidence. The State lacks a system of performance measurement to assess progress toward its goals and to inform managers and decision-makers, including during budget development.

BUDGET AND FISCAL REFORM RECOMMENDATIONS

Implementing a suite of reforms would significantly improve budgeting and fiscal management in New York State. Below are 4 strategies and 12 specific recommendations to achieve these strategies.

Some reforms would ideally be accomplished by constitutional amendments, while others can be implemented through State Law or simply changing the accepted practices around budgeting in New York. However, even many that should ultimately be enshrined in law and the Constitution can be implemented first in practice.

Some fundamentals in the budget process—such as revenue consensus, quarterly financial plans, and Quick Start—are sound but only if State leaders adhere to the process. A well-structured fiscal management and budget process is ineffective if government officials do not adhere to it. The Governor and leadership of the Legislature should commit to following the process and meeting existing deadlines.

CBC recommends the State:

I. Increase fiscal integrity and stability by standardizing accounting, building reserves, strengthening debt management, and eliminating illusory appropriations.

To develop and enact a fiscally sound budget, leaders should have accurate and reliable data, and well-crafted guardrails to make fiscal management decisions. Currently, the budget-making process is limited by accounting policies that do not adequately present the true fiscal condition, by inappropriate statutory limits on debt and reserves, and by an appropriation process that is not linked to actual spending. These recommendations focus on building a stronger fiscal foundation for the budget process to reduce risk and eliminate opportunities for mismanagement.

Recommendation #1: Manage, report, and balance the budget in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) on a modified accrual basis.

New York State has a balanced budget requirement. The Constitution and State law requires that the Executive Budget proposed by the Governor and the enacted budget passed by the Legislature be balanced. The balanced budget requirement is intended to help the State live within its available resources. However, it is lacking in the absence of specifying the accounting basis used to budget, by the fact that the requirement applies only to the General Fund, and by not requiring balance throughout the year including the year end results.

Currently, the State uses cash accounting, which counts spending when money is disbursed and receipts when monies are received—in other words, when the money changes hands. The modified accrual basis defined by GAAP recognizes when costs are incurred, measurable, and imminently due (expenditures) and resources when they are earned and available (revenues). Cash basis accounting is particularly susceptible to fiscal gimmickry to achieve budget ‘balance’ by shifting spending or revenue across time periods, which can create the illusion of budget balance even when the costs of government exceed the intake of resources to pay for them.17 In fact, these types of cash shifts have played out over many years in the New York State budget.

cash disbursement in the next year, even though the cost was incurred during the current year. (See footnote 18.)

The State Constitution directs the Governor to propose a budget with “revenues sufficient to meet such proposed expenditures.”19 The 2007 budget reforms further require that the “legislature shall enact a budget for the upcoming fiscal year that it determines is balanced in the general fund.”20 Both provisions have been interpreted to apply budget balance on the cash basis of accounting; according to DOB, “The State Constitution and State Finance Law do not provide a precise definition of budget balance.”21 As other areas of the Constitution and State Finance Law explicitly require reporting of fiscal information on a cash basis, DOB writes, “Unless clearly noted otherwise, all financial information is presented on a cash basis of accounting” in the State’s fiscal documents.22

Furthermore, the State’s balanced budget requirement applies only to the General Fund, which is less than half of total spending. In fiscal year 2023, the General Fund represents $96 billion of the total $222 billion cash spending plan. State Operating Funds ($123 billion) is a more comprehensive measure of the State’s operating budget because it includes all State-generated revenues and expenditures, including special revenue and debt service funds in addition to the General Fund. The State itself recognizes the benefit of State Operating Funds as a basis for measuring State costs rather than just the General Fund; within the Financial Plan, DOB writes, “As significant financial activity occurs in funds outside the General Fund, the State Operating Funds perspective is, in DOB’s view, a more comprehensive measure of operations funded with State resources (e.g., taxes, assessments, fees and tuition).23 Shifting to State Operating Funds would eliminate certain distortions in operating activities and provide a more complete picture of State spending.”

Lastly, the balanced budget requirement does not have a mechanism for validating that the budget is balanced and correcting a deficit if it exists. It is therefore important to have some external evaluation of whether the budget is balanced when it is passed. This responsibility is a difficult one, requiring an entity which is not party to budget negotiations to certify that the assumptions made by the Governor and the Legislature are compliant with the balanced budget requirement. The entity best positioned to make such an evaluation is the State Comptroller. The Comptroller should assess the enacted budget and quarterly financial plan updates to determine whether they are compliant with the balanced budget requirement. If the budget is determined to have a deficit, the Governor and Legislature should be required to make modifications to achieve balance, or, absent that, the Governor should institute across-the-board reductions.24

The State should modify its budgeting and reporting practices to conform to four key features, which should be codified in law and ultimately adopted by constitutional amendment:

- Budgeting and reporting should be based on modified accrual basis of accounting, recognizing revenues when they are earned and available, and expenditures when they are incurred, measurable, and imminently due, in accordance with GAAP;25

- Balance should be applied to State Operating Funds, not only the General Fund;

- Balance should be required for the Executive Budget, the Enacted Budget, and year-end results; and

- Balance should be assessed by the State Comptroller for the Enacted budget and subsequent financial plans.

Recommendation #2: Strengthen the Rainy Day Fund by raising deposit and balance caps, combining all reserve funds, and mandating deposits when revenues are strong.

Rainy Day reserves provide a critical fiscal backstop in the event of an economic downturn or emergency, allow states to continue supporting public services and operations when they are most needed, and signal fiscal strength to lenders. A well-structured reserve fund system supports adding to the funds during economic good times and limiting the funds use only to times of recession or severe emergency.26

The State’s principal reserves totaled $9.0 billion at the end of fiscal year 2022. This included $3.3 billion in the Rainy Day funds (the Rainy Day Reserve and Tax Stabilization Reserve) and $5.7 billion in the Reserve for Economic Uncertainties. Only the Rainy Day funds have strict rules about withdrawals. If the Rainy Day funds are lockboxes, the Economic Uncertainties reserve is a shoebox; it is still savings, but not sufficiently restricted. Governor Hochul deserves credit for leading the State in 2022 to amend the structure of the Rainy Day Reserves fund, and to increasing total reserves to $19 billion by the end of fiscal year 2025.

Despite making the maximum allowable deposit of $843 million in fiscal year 2022, the Rainy Day funds are inadequate. The current balance is equal to 2.8 percent of State Operating Funds disbursements in fiscal year 2023, ranking 45th among all states.27 This is significantly lower than the $27 billion that would be needed to cover two years of average recessionary receipt shortfalls plus one percent spending growth. The persistent inadequacy of the State’s reserves was abundantly clear at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the State’s contingency plan for addressing recession-induced tax shortfalls was to cut critical programs by as much as 20 percent.28

The rules across the reserve accounts vary in breadth and scope. The Rainy Day funds are comprised of two separate accounts. The first, the Rainy Day Reserve (RDR), has an annual deposit cap of 3 percent of General Fund disbursements and a balance cap of 15 percent of General Fund disbursements. The RDR caps were raised in 2022 at Governor Hochul’s urging, arguably the most positive fiscal management improvement in recent years, allowing the State to add billions to its lockbox and prepare for fiscal shocks. Previously, the caps had been deposits of 0.75 percent and a balance of 3 percent.

Funds can only be transferred out of the RDR for catastrophic events such as war or disaster, or for economic downturns. An economic downturn is tightly defined as a period in which the State Department of Labor calculates five consecutive months of decline in a composite economic index.

The second account, the Tax Stabilization Reserve (TSR), also is limited in size of deposits and balance. Up to 0.2 percent of General Fund disbursements may be added to the TSR each year, and the total balance is limited to 2 percent of General Fund disbursements. Funds from the TSR are only transferred out if tax receipts are below prior years’ receipts.29

In part because the caps on deposits and balance in the RDR are too low, the State at times deposits available receipts into other reserve funds. The primary such fund is the Reserve for Economic Uncertainties, a non-statutory fund with no restraint on transferring or replenishing the funds. Despite having no constraints on its size or use, the Economic Uncertainties reserve is considered one of the State’s principal reserves.

While recent changes strengthened the State’s reserves, the State should further bolster them to increase its ability to weather a rainy day. Even after being increased, the current balance limits prevent the State from saving the $27 billion needed to weather a two-year tax receipts loss and support existing services. Other key elements of a sound Rainy Day Fund are also lacking, such as requirements for automatic deposits in periods of strong revenue growth. The State should implement five reforms:

- Combine the TSR into the RDR. The TSR and RDR serve the same function: to set aside funds in case State tax receipts fall significantly short. Two accounts are unnecessary and the TSR’s withdrawal limitations are inadequate. The balance of the TSR should be transferred into the RDR to form a single Rainy Day Fund.

- Transfer other economic contingency reserves into the Rainy Day Fund. The current balance in the Reserve for Economic Uncertainties should be transferred into the Rainy Day Fund to protect those savings for a rainy day.

- Eliminate the deposit cap and raise the balance cap to 30 percent of State Operating Funds. The cap on annual deposits should be eliminated; the State should be able to deposit as much to the Rainy Day Fund as it deems feasible in a given year. A total balance of 30 percent would be sufficient to allow the State to cover two years’ worth of tax receipts losses under a typical recession plus allow for two years of 1 percent spending growth. Shifting the basis of the cap from General Fund Disbursements to State Operating Funds would better reflect total spending supported by State revenues and thus the base needing support. In the event that the State has already reached the balance cap in the Rainy Day Fund, automatic deposits should instead be made to the Retiree Health Benefits Trust.

- Require automatic deposits in years of strong receipts growth. One of the State’s failures during the 2010’s—from the Great Recession to the COVID-19 pandemic—was missing the opportunity during a strong economic expansion to significantly bolster reserves. As the economy grew, the State also received $15 billion in one-time settlement proceeds, which were a prime candidate for deposit to the Rainy Day Fund.30 Despite the prolonged availability of cash, the State only added $1.2 billion to the RDR from fiscal year 2008 to fiscal year 2021.

These opportunities would not be missed if the State were required to make automatic deposits, instead of them being ad hoc and optional. Tying deposits to tax receipt growth would add funds to the Rainy Day Fund in particularly strong economic periods. Automatic deposits equal to two-thirds of common rate and base tax receipts growth in excess of 2 percent would be sufficient to make meaningful deposits to the Rainy Day Fund. If from fiscal year 2011 to fiscal year 2020 the State had made these automatic annual deposits, plus added three-quarters of its one-time extraordinary receipts, the balance in its Rainy Day Fund would have exceeded $23 billion in 2020.31 - Codify the Rainy Day Fund in the State Constitution. The Rainy Day Fund should not be susceptible to simple statutory changes from time to time. Codifying the Rainy Day Fund as part of the Constitution would strengthen the lockbox and better protect its balance.

Recommendation #3: Strengthen the debt cap.

The Debt Reform Act of 2000 limits the amount of outstanding debt and annual debt service costs. However, these limits are easily subverted and exclude some debt guaranteed by the State. The debt cap should be broadened to include all State-supported debt and codified in the Constitution to ensure debt and debt service are affordable.

The caps are calculated based on the strength of the state’s economy and fiscal condition, aiming to prevent the State from issuing debt its tax base cannot repay, and require the State manage its debt to avoid unsustainable debt service costs. Specifically,

- Outstanding State-supported debt is capped at 4 percent of total NYS personal income;

- State-supported debt includes all General Obligation (GO) bonds and tax revenue-backed bonds, but excludes State-guaranteed debt (a relatively small amount of debt issued by State authorities with the full faith and credit of the State) or to debt issued by State authorities which is not backed by State resources (debt issued by entities such as the Dormitory Authority, Metropolitan Transportation Authority, and Urban Development Corporation);

- Annual debt service is capped at 5 percent of All Funds receipts; and

- The cap was phased in beginning in 2000, and generally applies to all State-supported debt issued after April 1, 2000.32

The original memo in support of the debt cap stated that it is, “intended to ensure that both debt levels and debt service costs remain affordable and that debt continues to be prudently managed. The prohibition on issuing debt if these caps are exceeded provides the State with a substantial incentive to treat these caps as absolute limits on debt that should never be breached.”33

The main flaw with the State’s debt cap is that it can be circumvented through regular legislation since it is not in the Constitution. During the pandemic, the State exempted billions of dollars in new borrowing that should have been subject to the cap. This was a pandemic-induced debt and cash management decision that added billions in outstanding debt and increased out-year debt service costs. Prior to the pandemic, the State had $51.8 billion in outstanding debt subject to the cap, comfortably within the cap of $55.5 billion.34 The Fiscal Year 2021 Enacted Budget, however, created exemptions to the cap that allowed the State to issue debt for non-capital purposes outside of the cap. Now the State holds roughly $19 billion in additional uncapped outstanding debt plus future uncapped debt service costs. By fiscal year 2027, State-supported debt will stand at $88 billion, considerably higher than the $71 billion expected prior to the debt cap exemptions.35 While it is reasonable to have the option of flexibility in events such as COVID, this example highlights the ease with which the debt cap may be subverted for non-emergency circumstances. It would be appropriate for a stronger debt cap to allow for limited exceptions in the event of emergencies and natural disasters similar to the Rainy Day Fund.

The second shortcoming of the existing cap is that it exempts some types of debt that are backed directly by the State. Specifically, about $30 million of State-guaranteed debt is not subject to the cap despite being issued by the State with the full faith and credit of the State.36

For the cap to be more effective, it should be broadened to include all debt to be repaid from State resources – except limited exceptions for debt issued in an emergency—and codified in the Constitution.

Recommendation #4: Tightly tie appropriations to planned spending by reducing unfunded and undefined spending authority.

Appropriations legally authorize the State to spend up to a ceiling for a specific project or purpose. However, four problems with the State’s appropriations impede sound fiscal management: significant, unneeded re-appropriations; lump sum appropriations; “dry appropriations” that have no receipts to fund them; and lack of a crosswalk between appropriation authority and planned spending in the financial plan. Addressing these four problems by aligning the level of appropriations tightly to planned spending would facilitate prudent fiscal decisions and increase transparency.

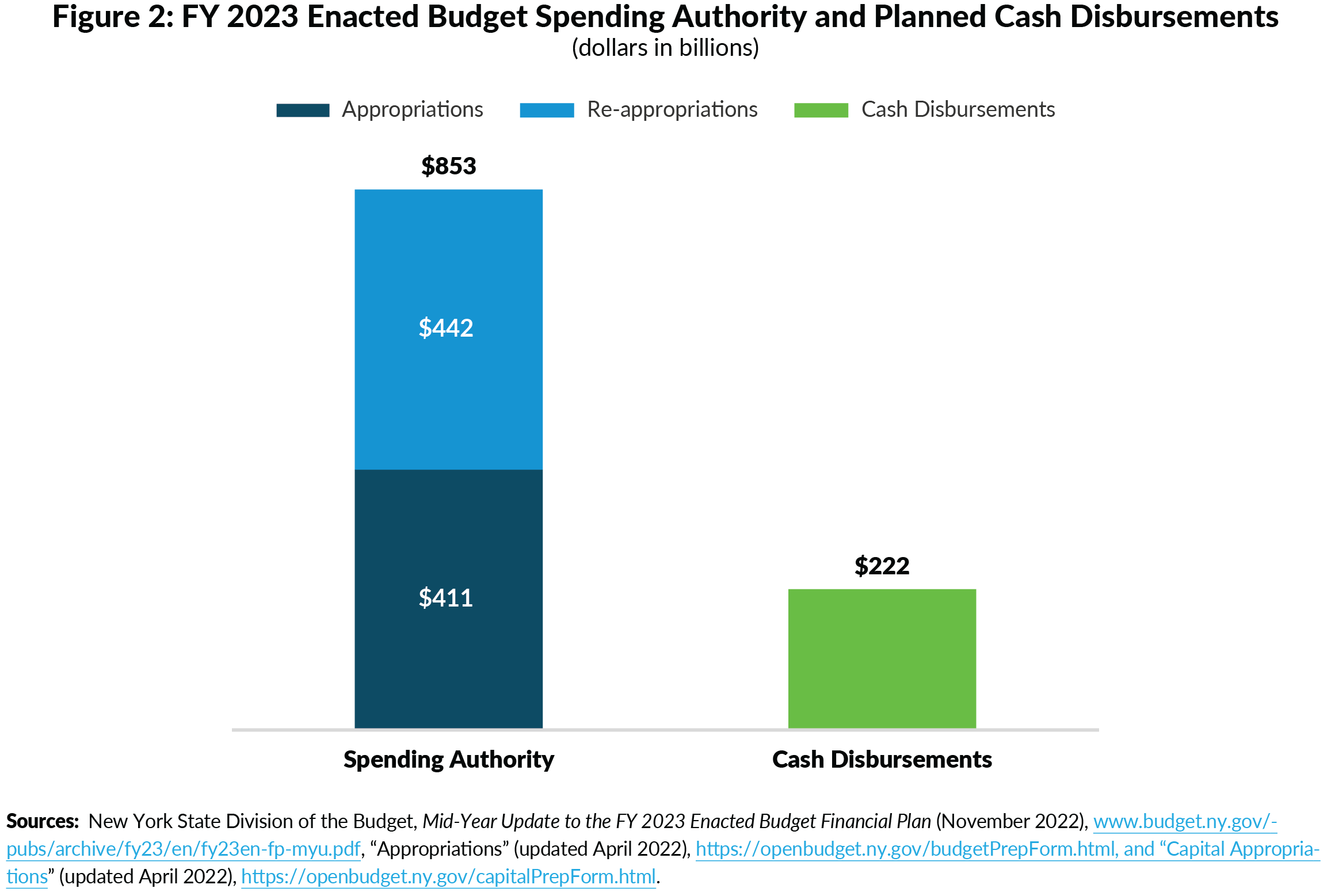

Each year, the budget appropriates funds for programs and functions. Since the appropriation is a ceiling, there is generally some unspent appropriation authority remaining at the end of the year. In the subsequent years’ budgets, the unspent authority may be “re-appropriated” alongside new appropriations for the new fiscal year. Over time, funds may be repeatedly re-appropriated. As a result, total sending authority available to the State during the year—the sum of both all new appropriations plus all re-appropriations—far exceeds actual planned spending. (See Figure 2.)

In other words, the Executive is authorized to spend far more than the State expects in receipts and not all of this authority is meant to be spent for several reasons:

- Nearly half of spending authority is from re-appropriations, which are mostly vestigial spending authority;

- Some appropriations, including those for Medicaid and school aid, cover a two-year period to ensure funding is available if the following year’s budget is late;

- There are “dry appropriations,” where the appropriation authority partially exceeds the planned spending or where the appropriation is never expected to be spent at all; and

- Many capital appropriations are expected to be spent over multiple years.

Excess spending authority provides the State flexibility, but also creates fiscal risk that actual spending could far outpace plans. Furthermore, there is little link between the State financial plan and appropriation bills; the public and stakeholders do not know the relationship between what is appropriated and what is actual planned to be spent, and consequently sometimes believe there is funding for programs where none exists. Four reforms to the appropriation process would reduce overspending risk and increase alignment between the level of funds appropriated and spending in the financial plan:

1. Appropriations for grants to local governments and State operations spending should be equal to the amount of planned spending in the coming year. Appropriations for grants to local governments and State operations should equal planned spending because unnecessary spending authority creates fiscal risk that actual spending could exceed what the financial plan accommodates. While some re-appropriations, such as those for multi-year contracts, are helpful, most re-appropriations are unnecessary. Appropriations for non-capital purposes should be made only at the level necessary to fund planned spending for the coming year, and to allow for the encumbrance of multi-year contracts, as needed.

The State may, during the year, need to adjust spending up or down in certain programs, but it does not need to enact excess appropriation authority to allow for mid-year management. Options exist in State law to transfer or interchange authority between appropriation lines administratively. These budget neutral options allow the State to make limited adjustments to spending on individual programs, without jeopardizing the financial plan.37 The Legislature and Governor can also modify the budget legislatively during the course of the year, and add new appropriations if absolutely necessary.

2. Appropriations should be for specific programs rather than lump sums with broad spending authority. The State should not enact lump sum appropriations that authorize spending on a broad range of projects or purposes to be determined and allocated at a later date. Lump sum appropriations do not allow the public to know what programs will be funded. The practice also encourages wasteful spending that does not maximize public benefit or return on investment. The State Constitution addresses the need for appropriations to be written for a specific purpose, stating, “No money shall ever be paid out of the state treasury or any of its funds, or any of the funds under its management, except in pursuance of an appropriation by law … and every such law making a new appropriation or continuing or reviving an appropriation, shall distinctly specify the sum appropriated, and the object or purpose to which it is to be applied.”

Specification of some appropriations are still quite broad. The appropriation for the “Local Community Assistance Program” (LCAP), included in the fiscal year 2023 enacted budget, demonstrates several problems with lump sum appropriations (see text box).38 First, the uses for this appropriation are broad, bordering on universal. Second, the allocation of the funding is not subject to negotiation between the Governor and Legislature; when the Legislature passes the bill that appropriates this money, the Governor is free to disburse it unilaterally. Third, this appropriation is eligible to be financed with State bonds, which means the State can borrow money today to pay for what may be low-value projects and require future budgets to pay off the debt. Fourth, there is little transparency surrounding the projects that are ultimately funded as there is no requirement for the disclosure of the recipients, purposes, and amounts of funds granted from this lump sum pot.

LOCAL COMMUNITY ASSISTANCE PROGRAM 185,000,000

Capital Projects Funds – Other Capital Projects Fund – 30000 Local Community Purpose

The sum of $185,000,000 is hereby appropriated for the Local Community Assistance Program. Funds appropriated herein shall be for grants for the payment of the capital costs of acquisition, design, construction, reconstruction, demolition, rehabilitation and improvement of an existing or proposed facility or other property real and personal, and other appurtenances thereto; and the acquisition of equipment and other capital assets with a useful life of not less than ten years purchased for installation or use in infrastructure that is owned or controlled by the grant recipient or appurtenant thereto. Eligible purposes shall include but not be limited to projects that support community development or redevelopment, revitalization, economic development, economic sustainability, arts and cultural development, housing, public security and safety and local infrastructure improvement or enhancement. Eligible entities may include municipal and state governmental entities, public authorities and not-for- profit corporations. Individual grants issued pursuant to this appropriation shall be in an amount no less than $50,000. Notwithstanding any provision of law to the contrary, funds appropriated herein may, subject to the approval of the director of the budget, be (i) interchanged, (ii) transferred from this appropriation to any other appropriation of any state department, agency, public benefit corporation, or public authority, or (iii) suballocated to any other state department, agency or public benefit corporation, to achieve this purpose................ 185,000,000

3. “Dry” contingency appropriations should only be available for emergency response and accessible only if offset by spending reductions or new resources. The largest dry appropriations take the form of contingency line items to allow the State to respond to emergencies or other unforeseen circumstances without need to reconvene the Legislature to enact supplemental appropriations. Some of these dry appropriations are small and narrowly defined. For example, a $40 million appropriation for public health crises allowed Governor Hochul to quickly fund reproductive health services following the Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization.39 Other dry appropriations are far broader and far larger. For example, watchdogs have repeatedly called for the elimination of billions of dollars in dry, lump sum appropriations because they created a pot of broad unilateral spending authority with no cash budgeted for them. This means they could be spent on nearly any purpose and—because there was no cash behind them—at the expense of other areas of the budget.

To allow for rapid response via contingency appropriations without leaving broad, unfunded authority, as part of appropriation reform, the State should only permit the inclusion of dry appropriations if they are for emergency response and used only if there is a plan for offsetting the unbudgeted spending via other spending reductions or additional revenues.

4. Each financial plan update should include a crosswalk from appropriations to the financial plan. The budget’s two key elements—the bills and financial plans—provide necessary but differing information that cannot be aligned. There is no crosswalk between the appropriation bills and the financial plan, which makes it unclear which appropriations are ‘dry.’ Crosswalks should be included in budget documentation to tie appropriations in the bills to planned spending in the plans.

II. Improve budget decisions by generating, publishing, and ensuring adequate time to use critical decision-relevant information.

The State budget suffers from a lack of adequate information to make sound financial decisions and opacity at most stages of budget-making. Often proposals are made and the budget is finalized without the multi-year fiscal data that should be considered by the Legislature. Absent that data, decisions are made for the upcoming and future years without knowing how much initiatives will cost, when those bills will come due, and whether resources are available to support them. This is an issue of not only transparency, but of the quality of decisions being made. The public and stakeholders also do not have the information, which they deserve since it is their resources, and which would improve their advocacy, allowing it to be more fact-based. Furthermore, bills are often accelerated through the approval process with negligible time available for the legislators, public, and press to adequately evaluate their contents in time for the vote. Improvements to the availability of information and time in the budget-making process would improve decision quality and transparency for the public, press, and lawmakers.

Recommendation #5: Require financial plans to be published with the enacted and one-house budgets.

Basic financial plan tables are an essential component of any budget. Absent information about the sources of funds, how they will be used, and the net fiscal results of those two sets of actions, one cannot reasonably understand a budget or its implications. Basic financial plan tables are often missing or lag behind the State’s budget-making and implementation processes. While budget bills provide the statutory provisions that guide State programming and the appropriations that authorize State spending, the Financial Plan quantifies the budget, fiscal impacts, and budget balance for the upcoming year and three out-years. Providing basic financial plan tables with the one-house bills and the enacted budget is essential for everyone—from legislators considering proposals to stakeholders advocating to the public whose money is being spent—to understand the possible and actual implications of proposals and the final budget agreement.

The Constitution and State Finance law require the Financial Plan to be published with the Executive Budget but allow it to be published up to 30 days after completion of the Enacted Budget. The State also publishes quarterly financial plan updates by July 30 and October 30. Financial Plans are not required to accompany the one-house budget proposals or the re-introduced bills that make up the Enacted Budget. The absence of Financial Plan tables laying out budget balance, year-to-year growth, and other basic—but crucial—data prevents the public and lawmakers from assessing and comparing competing proposals, assessing the final budget before it is enacted, and understanding the budget when it is agreed to. While certain data points are presented in budget resolutions, floor debates, and press releases, the lack of basic tables means that legislators and the Governor act on budget bills either without knowledge of the full fiscal picture or having made the choice not to release this information to the public.

Earlier this year, CBC and other watchdog organizations wrote to the Governor and legislative leaders urging the State to publish basic financial plan data with the enacted budget; CBC has been calling on the Legislature to produce basic financial plan tables with their one-house proposals. While a full financial plan, whose 400 pages contain significant narrative and supporting data, is not feasible with the one-house and enacted budget bills, basic multi-year financial plan tables should be released with the one-house bills and the Enacted Budget, that, at a minimum include:

- At least one financial plan table each for All Funds, State Operating Funds, and the General Fund;

- Reasonably disaggregated receipts, disbursements, transfers, and allocations of fund balances; and

- Bottom line results showing budget balance or budget gaps.

Budget Cycle: Key Dates

During the budget cycle, there are several dates on which regular reporting requirements are to be completed by the Governor, Legislature, and Comptroller. These dates include regular financial plan updates and ‘Quick Start’ reports. At times, these deadlines have been ignored. In particular, the Quick Start process has been repeatedly ignored, especially by the Governor and Legislature.[40] Financial Plan updates have also been missed in the past. For example, when Governor Hochul was inaugurated in August 2021, the State’s first quarterly Financial Plan update was delinquent, and was delivered in the following weeks.[41] Failure to deliver required reports diminishes transparency and accountability. Skipping the Quick Start process undercuts the State’s intent to begin fiscal reviews early enough to inform an on-time budget. Fortunately, the State has made recent progress: Governor Hochul has delivered most financial plan updates on time, and every required party completed their Quick Start report and review requirements in 2021. In 2022, Quick Start did not occur as required because the midyear financial plan was not released on time.

Key reporting deadlines include:

- Mid-January or February 1 – The Executive Budget is required to be introduced by the Governor by the second Tuesday after the convening of legislative session (mid-January) most years or February first after gubernatorial election years.[42] The Executive Budget Capital Program and Financing Plan is also due at this time.[43]

- Mid-February or March 3 – Amendments to the Executive Budget are due within 30 days of the Executive Budget.[44]

- March 1 – Revenue consensus between the Governor and legislative leaders is due by March 1.

- May 11 (approximately) – The Enacted Budget Financial Plan is due 30 days after the Governor’s final action on the budget. Assuming budget bills are enacted on March 31, the Governor has 10 days to sign or veto legislation, putting the Financial Plan deadline around May 11.[45]

- July 30 – The first quarterly update to the Financial Plan is due 30 days after the conclusion of the first quarter of the fiscal year.[46] The Enacted Budget Capital Program and Financing Plan is also due on July 30 (or 90 days after the budget is enacted).[47]

- ]October 30 – The midyear update to the Financial Plan is due 30 days after the conclusion of the second quarter of the fiscal year.[48]

- November 5 – Quick Start reports are due from the Division of the Budget, Senate Finance Committee, Assembly Ways and Means Committee, and OSC.

- November 15 – The Quick Start public review meeting must be held.[49]

Recommendation #6: Require fiscal estimates with other legislation.

While most of the State’s new spending is added during the budget process, other bills with fiscal impacts are sometimes passed outside of the budget process. Currently, there is no requirement for an assessment of the fiscal impact unless the bill affects pension plans; this jeopardizes the condition of the financial plan and budget balance.50 Rather than have legislators pass laws that increase costs without a publicly available estimate, any bill with fiscal impacts should be required to have a fiscal impact statement.

Bills may be referred to the fiscal committees in both houses of the Legislature, where Committee members with fiscal expertise consider their impacts before a full vote. However, the reality is that these bills often pass through both committees and the full Legislature with little or no quantification of their fiscal impacts. Instead, bills are accompanied by fiscal notes such as “TBD,” “To be determined,” “Potential savings,” or other vague assessments. If bills with fiscal impacts are passed outside of the budget process, they may be accommodated in the financial plan with available resources. However, the greatest fiscal risk comes from enacting fiscal bills with unknown fiscal impacts. This is often a reason for gubernatorial veto on bills passed outside of the budget process.

The Legislature should be required to include quantified fiscal impacts for any bill that is expected to have a fiscal impact. However, implementing this requirement will entail operational challenges and costs as it adds to the necessary work of legislative staff. Thousands of bills are introduced every year, and hundreds pass both houses; in fact, 450 bills moved through the fiscal committees and passed both houses in 2022. Nonetheless, a clear and public assessment of the fiscal impact of a bill under consideration is a necessary part of making sound fiscal decisions and worth the effort.

Recommendation #7: Prevent the use of Messages of Necessity on budget bills.

Bills are constitutionally required to age prior to a legislative vote, but the Constitution also allows for a Message of Necessity that permits an immediate vote. While MONs should be infrequent, in reality, they have been used regularly during budget enactment to accelerate budget votes, requiring legislators to vote on long, consequential bills without sufficient time to review. Ultimately, the Constitution should be amended to explicitly prohibit MONs on budget bills, narrowly excepting tightly defined budget extenders, thereby allowing for a thorough review of the bills prior to passage.

The State’s Constitution lays out the process for passing bills, requiring that, before being voted on, bills must be available in their final form “at least three calendar legislative days prior to its final passage.” This process is referred to as ‘aging,’ allowing time for the bills to be read and analyzed by legislators and the public before a vote is held. However, the Constitution also allows for an exception to the aging rule, the “Message of Necessity.” A MON allows the Governor to transmit a note to the Legislature certifying necessity of an immediate vote without aging.51

In practice, MONs do not serve as a rare, emergency failsafe; a MON has been used on at least one budget bill in each of the past nine budgets. Generally, MONs are reserved for the last bill or bills to pass in the budget—often in a rush to meet the start of the upcoming fiscal year. Furthermore, those last bills are often omnibus, serving as the landing spot for the most significant and difficult budget actions which take the longest time to negotiate. This is a failure in transparency. Budget bills should be required to properly age so they may be reviewed before a vote is held.

When budget negotiations are not finalized before the start of the new fiscal year, the norm prior to 2011, the Governor and Legislature utilize emergency extenders to provide the legal authority to allow continuity of government. In enacting this recommendation, the Legislature and Governor may deem it necessary to allow for use of MONs on emergency extender bills, but any such exemption should be limited to extending appropriation authority in the same amounts as the prior year’s budget and for debt service costs.

The use of MONs should be explicitly prohibited in the State Constitution for budget bills, and the use of MONs for emergency funding extenders should be limited to appropriation authority at the prior year’s budget level and for debt service. Since a constitutional change would take years, the Legislature and Governor should work to expeditiously agree to budgets that allow bills to age before voting.

Recommendation #8: Implement comprehensive, transparent long-term capital planning processes.

The State’s capital budget—with more than $17 billion in planned annual spending on long-term assets such as roads, bridges, State-owned buildings, and other infrastructure—is a critical, but inadequately structured part of the budget process.52

Sound capital planning includes five steps: setting goals, assessing needs, identifying resources, developing a capital plan, and implementing that plan.53 The process of budgeting for capital projects requires its own type of planning; spending on assets that may last 50 years requires budgeting for state of good repair work over time and replacement or expansion over longer timeframes.

Unfortunately, the State’s capital planning process is lacking. While there are various capital planning activities in and across agencies, the State does not conduct and publish a comprehensive assessment of its capital needs across all areas, and develop a plan that prioritizes and funds investment is those needs based on identified and standardized measures. This is demonstrated by capital planning for transportation, which includes some allocations based on geographic parity instead of asset needs.54 Fortunately a recently enacted bill will begin to provide transparency on the condition of state roads and bridges.

State’s Capital Planning for Transportation Illustrates Shortcomings

For years, the State has engaged in a five-year transportation capital planning cycle with three fundamental flaws:

- The overall transportation capital budget was established based on a goal of ‘parity’ with downstate transit budgets. That is no way to set a capital budget; it should be set based on the needs of the assets and the resources available to pay for those needs.

- The selection of individual projects was partially driven by the creation of a memorandum of understanding between the representatives of elected leaders, rather than being based solely on prioritizing the most urgent needs.[55]

- There is no transparency on the assessed needs of the State’s assets, although a recently enacted bill will begin to provide greater transparency on the condition of state roads and bridges.[56] Worse, the limited and lagging needs assessment that the State does bares out that the condition of transportation capital assets is deteriorating, and deferred needs are ballooning.[57]

To remedy the shortcomings in existing capital planning and budgeting, the State should implement a public, long-term, comprehensive capital planning process that would reduce deferred needs and provide long-term savings as assets are maintained in a state of good repair. The State has made initial steps in the past decade: the one-time NY Works process laid out a long-term vision for State infrastructure in 2013 and the State began to procure external experts to develop an improved capital planning and budgeting process in 2017.58 But, five years later, the State’s has yet to implement the fundamental reforms that are needed.

III. Bolster oversight and accountability by appropriately strengthening fiscal monitors.

Not all of the work to build a sound and transparent budget can be done by the Executive and Legislature themselves. The budget process is well-served by the inclusion of non-voting external actors with expertise to evaluate the State’s fiscal condition. These actors should be empowered with sufficient resources and authority to monitor the budget and the State’s fiscal condition, and to provide oversight.

Recommendation #9: Fully fund the Authorities Budget Office.

The Authorities Budget Office (ABO) is an independent office tasked with making New York’s public authorities more accountable and transparent. The ABO oversees close to 600 State and local authorities and even more authority subsidiaries with a total of $273 billion in public debt.59 The office is funded by an assessment on public authorities.60 Current funding is insufficient for the ABO to fulfill its critical mission; funding should be increased and indexed to inflation.

The ABO was established with the Public Authorities Accountability Act of 2005, and tasked with three main functions to ensure that public authorities comply with Public Authorities Law: first, review and analyze authority operations, practices, and reports; second, make recommendations to the Governor and Legislature regarding opportunities to improve the performance, structure, and oversight of authorities; finally, maintain a comprehensive inventory of all authorities and subsidiaries.61

The Public Authorities Reform Act, signed into law in 2009, restructured the ABO and strengthened its mandate.62 The Act gave the ABO greater oversight and accountability authority, empowering it to:

- Recommend debt limits for authorities that lack debt caps;

- Recommend compensation for board members;

- Require board members to adopt a written acknowledgement of their fiduciary duties;

- Review and recommend changes to board member term limits;

- Receive and act on complaints from the public;

- Initiate formal investigations;

- Issue subpoenas pertaining to investigations;

- Publicly warn and censure authorities;

- Recommend dismissal of board members to appointing authorities;

- Report criminal activities to the Attorney General;

- Collect, analyze, and disseminate information on the finances and operations of state and local authorities to the public;

- Promote good governance principles through training and technical assistance and the issuance of policy guidance and recommended best practices; and

- Investigate complaints made against public authorities for non-compliance or inappropriate conduct.

Furthermore, the Act required public authorities to report additional information to the ABO on a regular basis beginning in 2009. For example, authorities are required to report data concerning their grant and subsidy programs, employees, enabling legislation, board performance evaluations, and financial plans.

In the “fiscal implications” memo associated with the Public Authorities Reform Act of 2009, the Legislature noted that to fully act on its mandate, the ABO would require legal and investigatory staff, as well as analytical and compliance personnel.63 The Legislature further stated, “these resource needs for the office could total an additional $2.7 million on an annualized basis.” Based on that initial estimate, the ABO should have been funded at $4 million in 2010. Adjusting for inflation, the $4 million initial estimate is equal to more than $5 million in current dollars.64

However, the ABO’s budget has not been increased adequately and the ABO does not conduct more than a handful of investigations and reviews. Annual funding for the ABO should be immediately increased to $5 million and adjusted for inflation going forward. This is a reasonable and needed investment in an entity tasked with providing oversight for hundreds of authorities and billions in public debt and spending.

Recommendation #10: Establish the Independent Fiscal Analysis Office.

Developing and implementing a sound budget calls for reliable and timely analysis of the financial plan and fiscal legislation. This need extends beyond staff within the State DOB or State Legislature, and extends to other governments, advocates, and the public. In some other jurisdictions, an independent office fills this role. New York State should establish as Independent Fiscal Analysis Office to fill this void and provide rigorous, nonpartisan data analysis and monitoring of the State’s budget.

New York State has considered creating an office like this for many years. The 2005 ballot measure to amend the budget process included a recommendation for a State Independent Budget Office that CBC found would have lacked true independence and a formal oversight role. The broader measure failed before voters, but the Legislature introduces bills annually to create such as office; some proposals mirror the 2005 approach or would house this function within the Legislature, rather than creating an independent entity.65

Independent budget offices like the Congressional Budget Office or the New York City Independent Budget Office provide analysis of the budget and fiscal policy from within government and can provide a useful framework for how to establish such an office. CBC recommends a framework that draws from some of the components of the existing legislative proposals as well as best practices:

- Governance: Oversight by an 11-member Advisory Board with one appointment of a fiscal policy or public budgeting expert from each of the Comptroller, Attorney General, the chairs and ranking members of the legislative fiscal committees, the Assembly Speaker, and the Senate Majority leader plus three appointees from the Governor (which must include one representative each from labor, business, and local government).

- Leadership: Directed by an Executive Director selected by the Advisory Board and jointly appointed by the Speaker and Majority Leader to serve a seven-year term, who may also be removed by separate three-quarters votes in each house of the Legislature.

- Access: Provided with direct access to State databases, such as the Statewide Financial System, Grants Gateway, Medicaid Data Warehouse, and other relevant resources needed to complete timely and accurate analyses of State spending and programming.

- Funding: Benchmarked to funding of the Division of the Budget (for example, 20 percent).

- Budget responsibilities: Report on Executive and Enacted budgets, testify at joint budget hearings, complete quarterly financial plan reviews, and participate in Quick Start and Revenue Consensus reporting.

- Legislative responsibilities: Develop fiscal estimates of bills assigned to legislative fiscal committees, and other significant bills as requested by leaders and fiscal committee chairs or ranking members.

- Other responsibilities: Serve as a non-voting member on State revenue-reliant authorities’ boards (Metropolitan Transportation Authority, Thruway Authority, Dormitory Authority of the State of New York, etc.), maintain a dashboard of public performance data for key programs, and conduct analyses of significant revenue and spending policies.

This recommended framework establishes an office which is sufficiently independent from direct control by any one elected leader in State government and maintains direct access to governmental data and operations, but which does not have direct authority that would subvert the work of New Yorkers’ elected representatives. Its work would provide timely and accurate analyses of the State’s fiscal condition, including greater insight into the impacts of all bills which are likely to have a fiscal impact.

Recommendation #11: Fully restore Comptroller’s oversight.

The Office of the State Comptroller (OSC) provides oversight of State contracts and grants, as required by law. Comptroller oversight is critical for ensuring the integrity of State contracts. In 2019, OSC received 21,282 contract transactions valued at $102.4 billion.66 OSC identified multiple opportunities to renegotiate costs and save millions of dollars for agencies and taxpayers.67

In 2011, State legislation removed some of the Comptroller’s authority to conduct preemptive reviews of State University of New York (SUNY), City University of New York, and Office of General Service contracts. At the time, the Governor’s office asserted that the changes were necessary to streamline the State’s bidding process and maintained that there were other avenues of oversight. Yet, the erosion of OSC oversight preceded a different host of problems. A bid-rigging scandal associated with Fort Schuyler and Fuller Road Management Corporations, two nonprofits affiliated with SUNY, resulted in the 2018 conviction of State officials. Pre-audit review might have helped avoid this case.

Following years of advocacy by CBC and other budget and government watchdogs, the Governor and the Comptroller signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) in 2019 that restored Comptroller oversight of these contracts.68 The MOU restored OSC pre-audit review of SUNY, CUNY, their Construction Funds, SUNY Research Foundation, and OGS centralized contracts. The MOU additionally stated that SUNY Research Foundation would coordinate with SUNY to grant the OSC pre-audit review of contracts of $1 million or more involving Fort Schuyler and Fuller Road Management Corporations by January 1, 2020. Then, in 2022, the State Legislature passed a bill codifying this MOU into State law.69 This bill is still awaiting the Governor’s signature and should be signed once delivered.70

IV. Improve accountability for budgeted spending.