Balancing Act

Alternatives that Balance the NYS Budget without Raising Income Taxes

The New York State Fiscal Year 2022 Executive Budget closed significant budget gaps for fiscal years 2021 and 2022 using a combination of already granted federal aid, higher than previously projected tax receipts, proposed tax increases, and reduced and lower than expected spending. In addition, the budget assumes the State will receive $6 billion more of federal aid, which Governor Andrew Cuomo has described as a “worst case" scenario. Desired federal aid of $15 billion is presented as a “fair funding” case, which would allow some proposed actions to be rendered unnecessary.1 The “worst case” budget would raise personal income tax rates on high-income taxpayers to the highest in the nation, risking high-income earner flight and ongoing fiscal and economic consequences. However, reasonably shifting more capital financing to long-term debt and reducing unproductive economic development and low priority capital spending would provide sufficient resources to make the tax increase unnecessary, preserve the middle class tax cut, offset some of the other proposed spending cuts, and improve the State’s fiscal outlook.

Fiscal Year 2022 Executive Budget Gap-Closing Actions

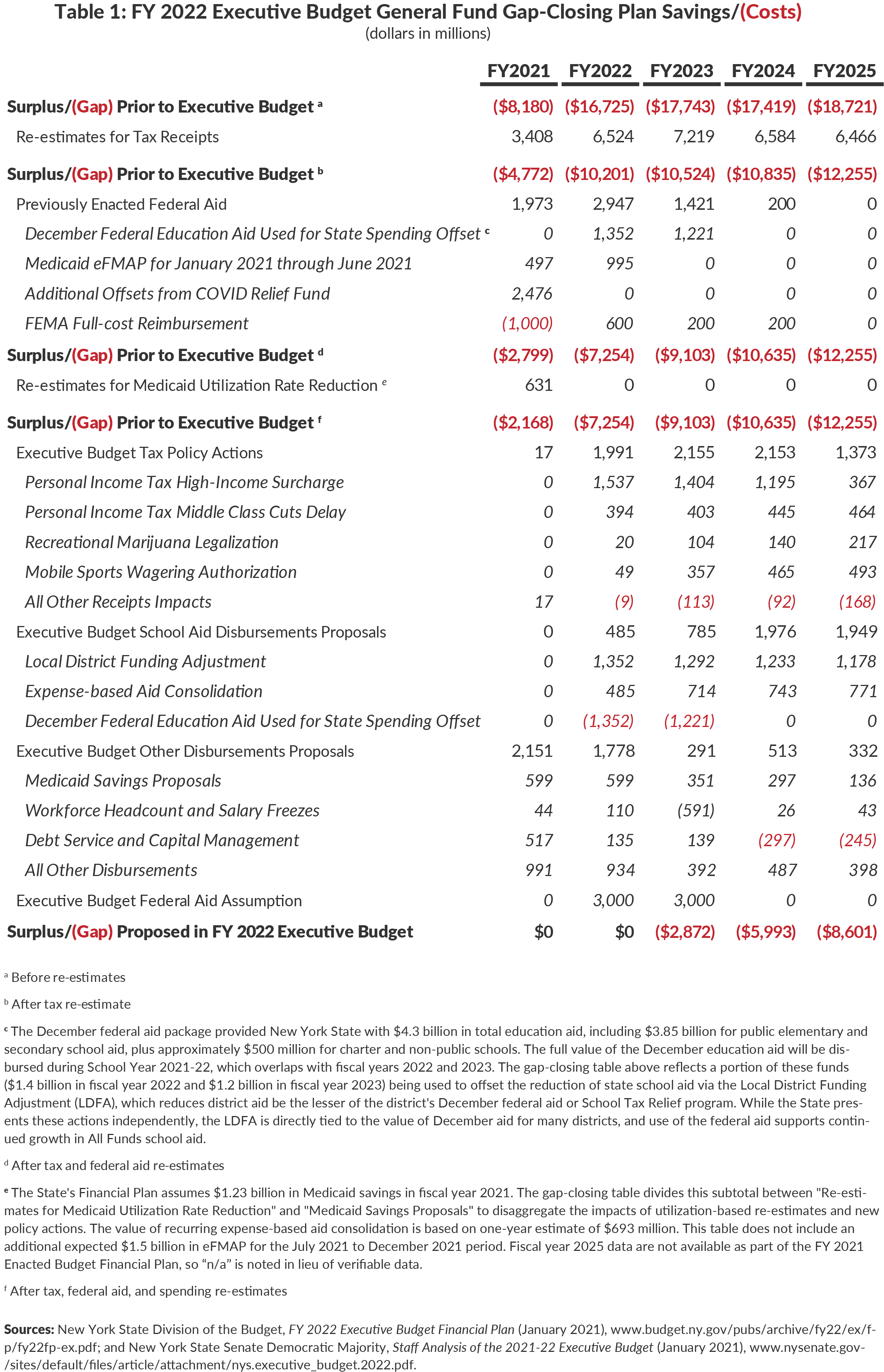

Last April the State initially estimated that the pandemic would cause tax receipts shortfalls of approximately $15 billion annually. When added to already existing budget gaps and unspecified local aid cuts, State budget gaps totaled $8 billion in the current year, $16.7 billion in fiscal year 2022, and exceeded $17 billion annually thereafter. (See Table 1.) However, higher than originally projected receipts, authorized federal aid, and savings from lower Medicaid utilization reduced the fiscal year 2021 and fiscal year 2022 gaps to $9.4 billion combined. To close these gaps, the budget proposes tax increases, delayed tax reductions, spending reductions, and assumes $6 billion in additional federal aid.

Re-estimates and Authorized Federal Aid

The receipts shortfall was less severe than expected. Annual receipts estimates increased between $3.4 billion and $7.2 billion between fiscal years 2021 and 2024. These additional receipts reduced the current and next fiscal year’s budget gaps to $4.8 billion and $10.2 billion respectively, resulting in the two-year cumulative $15 billion gap to be closed in the Executive Budget.

Federal aid ($4.9 billion in total) and lower than expected Medicaid spending provided additional gap-closing resources. The December federal aid package provided $4.3 billion in aid for schools, a portion of which offset proposed state school aid spending reductions. Net of the state funds spending reductions, federal education aid allows for school year-to-year growth in aid to districts of 7.1 percent.2 Continuation of the federal emergency declaration also provided two additional quarters of enhanced federal Medicaid matching funds ($1.5 billion), and additional uses of pandemic response funding and reimbursement offset another $2.5 billion in State costs.3 Lower utilization of services in Medicaid managed care also allowed the State to reduce planned spending by approximately $631 million in fiscal year 2021.4 As a result—before proposing policy or management changes—the State’s budget gaps for fiscal years 2021 and 2022 were reduced to $2.2 billion and $7.3 billion, respectively.5

Proposed Revenue Increases and Spending Reductions

To close the remaining gap and reduce future gaps the Executive Budget included a package of tax increases, a delayed tax reduction, and spending reductions. The tax proposals yield $2 billion of gap closing resources in fiscal years 2021 and 2022 and include the following:

- Personal income tax high-income surcharge: A temporary personal income tax surcharge is proposed on high-income earners in 2021, 2022, and 2023. The surcharge would be imposed at 0.5 percent beginning with filers with taxable incomes of $5 million, and would increase on a sliding scale to a maximum of 2 percent for earners with income over $100 million. Taxpayers affected may opt to pre-pay their 2022 and 2023 liabilities and receive a deduction equal to the pre-payment in 2024 or 2025. This proposal would generate an estimated $1.5 billion in tax revenue in fiscal year 2022, but the net impact would decrease incrementally over the life of the financial plan and actually reduce receipts in fiscal year 2026.6

- Personal income tax middle class cut delay: The proposal would delay for one year the incremental personal income tax rate reductions that were enacted in 2017. The proposal extends 2020 tax rates into 2021 and delays full implementation of the middle class tax cuts from 2025 to 2026. The delay also extends the “temporary millionaire’s tax surcharge,” which sets the State’s top rate at 8.82 percent, for an additional year.7 The original version of this surcharge was enacted in 2009 with a top rate of 8.97 percent and has been extended multiple times, including a partial reduction to the current rate of 8.82 percent enacted in 2012.

- Recreational marijuana legalization: For a third consecutive year, the Executive Budget includes a proposal to legalize adult use of recreational marijuana and tax commercial sales. The proposal creates a three-piece tax structure: a tax on sales from producers to retailers, a tax at the point of retail sale, and application of state and local sales tax rates. Revenues are used for administration, social equity purposes, and other purposes identified by regulators. When the market is fully mature, sales are expected to generate approximately $300 million in annual State tax revenue.

- Mobile sports wagering authorization: The budget authorizes the Gaming Commission to solicit proposals to allow one or more platform providers to operate mobile sports wagering within the state. The State would allow the distribution of gross gaming revenue to be determined following a solicitation for proposals by providers. Enactment is projected to yield up to $500 million annually by fiscal year 2025.

Proposed net expense savings offset $4.4 billion of the budget gaps in fiscal years 2021 and 2022 and between $1 billion and $2.5 billion in each of the following three fiscal years. The most significant reduction is in State spending for local education aid. Federal aid offsets some reductions in fiscal year 2022, and investment of remaining federal funds results in a large total increase in funding for schools in the near term, followed by a reduction and then relatively lower growth rates in the out-years. Savings from debt service and capital management, including uses of refundings and shifting timing of capital disbursements, provide another $652 million to close the gap in fiscal years 2021 and 2022 but increase costs in the future.8 Additional savings come from local aid reductions outside of Medicaid and school aid; these total $1.7 billion in the current and next fiscal years, declining to $413 to $537 million in the subsequent fiscal years. Details of the major savings actions include:

- School aid proposals: The State proposes two significant savings actions related to State spending on school aid beginning in fiscal year 2022. First, the Local District Funding Adjustment (LDFA) will reduce state aid in each district by the lesser of that district’s federal aid from the December federal package or the district’s School Tax Relief (STAR) program cost. This proposal will save approximately $1.3 billion in State funds annually, but in fiscal years 2022 and 2023 is offset by federal funds. Taken together, over the two fiscal years approximately $2.6 billion of the $4.3 billion in December federal education aid is effectively used to offset state costs. The remainder is invested as supplemental aid to public, non-public, and charter schools. Second, the Executive Budget proposes a consolidation of certain expense-based aids into a “Services Aid” with savings of more than $700 million on an annual basis.

- Medicaid savings proposals: The budget proposes legal and administrative policy changes estimated to reduce State Medicaid spending $599 million in each of the current and next fiscal years, and less than $400 million annually thereafter. This results in annual State share Medicaid spending increasing 3.6 percent in fiscal year 2021, and by 3.2 percent to 6.2 percent annually in each of the out-years.9 Details of these proposals have not been released to the public, continuing the State’s lack of transparency of Medicaid spending. The State has not released a scorecard of proposed actions, the statutorily-required monthly spending reports for the current year, or updated fiscal impacts of the Medicaid Redesign Team II’s enacted programmatic changes.10

- Workforce headcount and salary freeze: The Executive Budget continues a hiring freeze and administrative salary freeze. The State projects repayment of withheld salaries in fiscal year 2023, accounting for increased fiscal year 2023 cost of $591 million.11

- All other disbursements reductions: Throughout fiscal year 2021, the State has withheld up to 20 percent of certain local aid payments as a fiscal management strategy. The Executive Budget reduces the withholdings to 5 percent and makes the 5 percent reduction recurring. The Division of the Budget has provided little detail about the previous or future withholdings. Coupled with other unspecified local aid reductions, this is estimated to achieve savings of nearly $1 billion in fiscal year 2021 and $392 and $934 million annually beginning in fiscal year 2022.

Assumed Additional Unrestricted Federal Aid

Significant federal aid is likely, but the timing and amount are uncertain. The Biden Administration has proposed another major federal COVID response package that includes $350 billion for aid to state, local, and tribal governments.12 Details on the contents of this portfolio of funding remain largely unknown.

The Executive Budget assumes that the State will receive at least $6 billion in additional unrestricted federal aid.13 The Executive Budget uses half of this, along with the re-estimates and actions described above, to close the fiscal year 2022 gap. The remaining $3 billion is used to reduce what would have been a $5.9 billion fiscal year 2023 budget gap to $2.9 billion.

If the requested $15 billion aid is received, the State would reverse some of the Executive Budget proposals, including forgoing the personal income tax surcharge and middle-class tax cut delay, restoring contractual salary increases to State employees, avoiding some of the significant reductions to school aid, and avoiding other local aid cuts.14 This level of federal aid would provide enough new short-term relief to reverse all Executive Budget cuts and revenue raisers, and provide additional funding (after the other previous re-estimates are taken into account). Regardless of the value of future federal aid, the State also needs to prioritize level-setting of the State’s fiscal condition.

Future Budget Gaps

These actions would close the budget gaps for fiscal years 2021 and 2022 and reduce the fiscal year 2023 gap to a more manageable $2.9 billion. The gaps remaining in fiscal years 2024 and 2025 would be $6.0 billion and $8.6 billion, respectively. As a portion of State generated receipts, these still are significant and maintain the State’s fiscal vulnerability in the long run. These may even be understated given the out-year trajectory of school aid, which traditionally has been hard to restrain to the level anticipated in the budget, and the challenges the State has had in constraining Medicaid spending in the last few years.

Executive Budget Proposals: Implications and Alternatives

The impacts of the pandemic and recession are widespread and significant. The State fiscal impacts will last throughout the years of the financial plan. No matter what the level of federal aid, the State should take some actions to stabilize its long-run finances and these are unlikely to be without consequence. The State should make every effort to identify and implement actions that minimize the impact on New Yorkers, especially those most in need, and that keep New York a desirable place to live and work—a competitive jurisdiction that can create the jobs New Yorkers need and the resource base to support the services New Yorkers need and want.

In previous recessions, increased personal income taxes and reductions in school aid have been utilized to achieve a balanced budget. However, the proposed personal income tax rate surcharge on high-income earners heightens the risk that these residents will leave the State, taking their tax payments and possibly business interests with them. The top 1 percent of income taxpayers finance approximately 20 percent of the State Operating Funds budget through income taxes, and those with taxable income more than $10 million have an average a personal income tax liability of approximately $1.2 million.15 Losing these residents and funds would reduce the State’s ability to provide needed services.

The mobility risk is especially acute now for four reasons. First, this increase, when combined with New York City’s personal income tax, which is paid by most high-income earners in New York, will make New York’s combined top marginal rate 14.7 percent, the highest in the nation.16 Second, the federal cap on deductibility of state and local taxes enacted in 2017 exacerbates the differential between the tax cost of living in New York and lower tax jurisdictions. Third, the past 11 months of telecommuting and remote business administration and leadership have demonstrated the viability of being outside of New York. Finally, at least in the short term, some of the amenities that have made New York worth its higher cost of living and taxes, especially in New York City, are not available.

The State correctly proposed that this increase be temporary. While this could possibly mitigate the mobility risk, it is unlikely do so. Many may be hard pressed to believe the surcharge would be allowed to sunset given that the State’s “temporary” surcharge enacted 12 years ago to mitigate the impact of the last recession is still in force, having been extended numerous times including for five years just recently and for another year in this Executive Budget.

Alternative Strategies to Balance the Budget

In “New York State’s Hard Choices” the Citizens Budget Commission (CBC) identified two gap-closing strategies that could be used instead of some of the Executive Budget’s proposed tax increases, middle class tax cut delay and spending reductions.

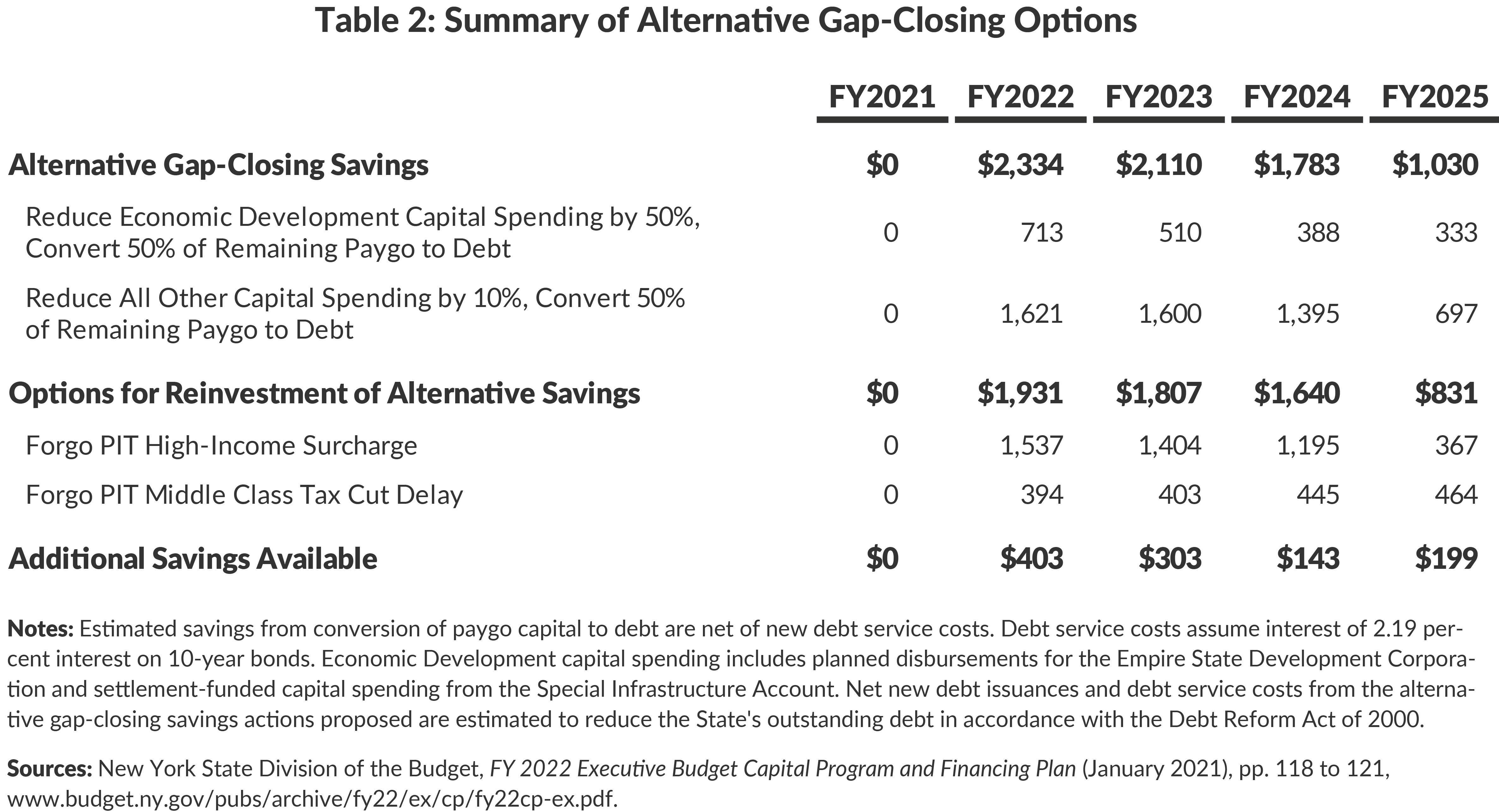

While incurring debt to finance operations costs should be a last resort, financing capital projects with debt structured with maturity proportional to a project’s useful life is a reasonable and equitable financing strategy. The State currently finances some of its capital projects on a pay as you go basis (paygo), which has the benefit of not constraining future budgets with added debt service. This is particularly important in New York, given its high level of outstanding debt. However, the gravity of the current fiscal situation makes the shift to debt financing reasonable, at least for the next few years. To avoid adding to already high outstanding debt levels, the State should focus its capital investments on the most critical projects during this period. If the State reduces its planned capital disbursements by 10 percent and finances up to 50 percent of the remaining paygo capital spending with debt, it would save $1.6 billion in fiscal year 2022. In subsequent years, the net benefit would diminish due to the new costs of debt service for the new debt, and the percentage of paygo-to-debt conversion can be eliminated by mid-year of fiscal year 2025.

The State also has been a leader in economic development spending, however this spending has not always proven to provide the benefits needed and expected.17 CBC has previously advocated for a pause in such spending to fully evaluate and understand its benefits. A 50 percent reduction in proposed economic development capital spending plus financing 50 percent of the remaining paygo spending with debt would yield another $713 million in fiscal year 2022.

Together, these changes provide $2.3 billion in budget savings in fiscal year 2022, $2.1 billion in fiscal year 2023, $1.8 billion in fiscal year 2024 and $1 billion in fiscal year 2025. (See Table 2.) These funds are sufficient to offset the receipts from both the high-income personal income tax surcharge and the middle class tax cut delay.

Furthermore, the actions provide an additional $403 million in fiscal year 2022, $303 million in fiscal year 2023, $143 million in fiscal year 2024 and $199 million in fiscal year 2025. This could be used to reverse a portion of the non-school aid spending reductions proposed in the Executive Budget for fiscal year 2022, including the local aid reductions and the contractual wage freeze. Furthermore, the resources available could also be used to offset a portion of projected gaps in the out-years.

Shifts to Minimize Future School Aid Reductions and to Reallocate Aid to High Need Districts

The Executive Budget proposes using all of the federal education aid granted in the December relief bill for school year 2021-22. Since school years cross fiscal years, $3.1 billion would be disbursed in fiscal year 2022 and $1.2 billion in fiscal year 2023. The result is that aid to schools, including the one time federal funds, would increase year-to-year by 7.1 percent in the school year 2021-22, but decrease by 8.7 percent in the following year. In effect, the use of one-time federal funds inflates spending to levels that are not sustained in the out-years.

Instead, the State should smooth the year-to-year fluctuations in aid to avoid a sudden drop-off. Since federal constraints on the December aid limit flexibility of these funds, the State should adjust timing of its own aid or flexible federal funds to the extent possible. This would not only dramatically decrease the planned year-to-year drop, but include more school aid for school year 2022-23.

In the out-years, total school aid would remain approximately constant. This does not mean that every school district’s aid should remain the same. The Executive Budget includes some proposed changes to school aid funding streams that will affect the total aid distribution once the non-recurring federal aid ends. The overall distribution approach, however, should focus on directing aid to high need districts and reducing aid to wealthier districts. Previous analyses have estimated that approximately $1.6 billion in State aid is disbursed to high-income districts that already support a sound basic education without State funding.18 Reducing aid to those districts would provide resources to increase aid to others.

Conclusion

The State faces an extremely challenging fiscal picture. Assumptions of additional federal aid are justified and reasonable. The State is right to effectively plan for the contingency of not receiving all the federal aid it desires. However, the State has alternative choices that would allow it to forgo the proposed tax increases and adverse spending reductions in whole or in part. These would help to sustain the State’s economic competitiveness and ability to support critical services, especially those most affected by the pandemic and which serve New Yorkers most in need.

Footnotes

- Governor Andrew Cuomo, Public Briefing on the New York State Executive Budget for Fiscal Year 2022 (January 19, 2021), p. 33, www.dropbox.com/s/ojxqkrpnev0lgti/2021%20budget%20ppt%20final.pdf?dl=0.

- The December federal aid package provided New York State with $4.3 billion in total education aid, including $3.85 billion for public elementary and secondary school aid, plus approximately $500 million for charter and non-public schools. The full value of the December education aid will be disbursed during School Year 2021-22, which overlaps with fiscal years 2022 and 2023. The gap-closing table above reflects a portion of these funds ($1.4 billion in fiscal year 2022 and $1.2 billion in fiscal year 2023) being used to offset the reduction of state school aid via the Local District Funding Adjustment (LDFA), which reduces district aid be the lesser of the district's December federal aid or School Tax Relief program. While the State presents these actions independently, the LDFA is directly tied to the value of December aid for many districts, and use of the federal aid supports continued growth in All Funds school aid.

- Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, P.L. 116-260 (2020).

- The Financial Plan assumes significant rate reductions for Medicaid managed care plans due to low utilization during the year. Managed care organizations are commercial insurers that are paid by the State to cover and coordinate the care of most of the State’s 6 million Medicaid enrollees. During the pandemic, coverage costs have apparently been reduced due to use of fewer and/or lower cost services. The magnitude of this reduction and the methodology for calculating it have not been made public, but it is assumed to generate $631 million in State share savings in fiscal year 2021 (the full value of $1.23 billion in fiscal year 2021 less savings of $599 million in fiscal year 2022).

- Subsequent to Executive Budget release, the US Department of Health & Human Services notified states that eFMAP is expected to be extended through at least December 2021, which would yield a further $1.5 billion in state gap-closing relief. See Norris Cochran, US Department of Health & Human Services, letter to state governors, (January 21, 2021).

- See Part A of S.2509/A.3009 of 2021; and New York State Senate Democratic Majority, Staff Analysis of the 2021-22 Executive Budget (January 2021), p. 21, www.nysenate.gov/sites/default/files/article/attachment/nys.executive_budget.2022.pdf.

- The State’s top rate of 8.82 percent was set to expire in 2024, but would instead expire in 2025. See Part B of S.2509/A.3009 of 2021.

- New York State Division of the Budget, FY 2022 Executive Budget Financial Plan (January 2021), p. 13, www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy22/ex/fp/fy22fp-ex.pdf.

- Growth rates are based on projected spending the Financial Plan, and adjusted for timing of payment deferrals and COVID-related federal aid. See New York State Division of the Budget, FY 2022 Executive Budget Financial Plan (January 2021), p. 109, www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy22/ex/fp/fy22fp-ex.pdf

- Andrew Rein, President, Citizens Budget Commission, before the New York State Medicaid Redesign Team, Public Comment to Submitted to the Medicaid Redesign Team II (March 2, 2020), https://cbcny.org/advocacy/public-comment-submitted-medicaid-redesign-team-ii.

- New York State Division of the Budget, FY 2022 Executive Budget Financial Plan (January 2021), p. 13, www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy22/ex/fp/fy22fp-ex.pdf.

- The White House, “Fact Sheet: President Biden’s New Executive Actions Deliver Economic Relief for American Families and Businesses Amid the COVID-19 Crises” (press release, January 22, 2021), www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/01/22/fact-sheet-president-bidens-new-executive-actions-deliver-economic-relief-for-american-families-and-businesses-amid-the-covid-19-crises/.

- New York State Division of the Budget, FY 2022 Executive Budget Financial Plan (January 2021), www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy22/ex/fp/fy22fp-ex.pdf.

- Governor Andrew Cuomo, Public Briefing on the New York State Executive Budget for Fiscal Year 2022 (January 19, 2021), p. 25 www.dropbox.com/s/ojxqkrpnev0lgti/2021%20budget%20ppt%20final.pdf?dl=0.

- The top 1 percent of personal income tax filers comprise 40.9 percent of the State’s total personal income tax liability, equal to approximately $20.2 billion in State tax revenue on a State Operating Funds budget of $102 billion. See: New York State Division of the Budget, FY 2022 Economic and Revenue Outlook (January 2021), p. 104, www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy22/ex/ero/fy22ero.pdf.

- Governor Andrew Cuomo, Public Briefing on the New York State Executive Budget for Fiscal Year 2022 (January 19, 2021), p. 33, www.dropbox.com/s/ojxqkrpnev0lgti/2021%20budget%20ppt%20final.pdf?dl=0.

- Riley Edwards, 10 Billion Reasons to Rethink Economic Development in New York (Citizens Budget Commission, February 2019), https://cbcny.org/research/10-billion-reasons-rethink-economic-development-new-york.

- Testimony of David Friedfel, Director of State Studies, Citizens Budget Commission, before the New York State Senate Joint Standing Committees on Education and on Budget and Revenues, Testimony on the Distribution of the Foundation Aid Formula as it Relates to Pupil and District Needs (December 3, 2019), https://cbcny.org/advocacy/testimony-distribution-foundation-aid-formula-it-relates-pupil-and-district-needs.