Overdue Bills

Time to Face the Reality of Rising Medicaid Costs

New York State’s Medicaid program provides health care coverage for more than 6 million New Yorkers at a cost approaching $80 billion annually. Medicaid is the single largest expense in the State budget, comprising more than one of every three dollars spent.1 The program’s significant fiscal impact and importance to enrollees, providers, and many others makes accurate budgeting of the program an important responsibility of the executive and legislative branches. The Governor’s Medicaid Redesign Team (MRT) took significant action and constrained spending growth between fiscal years 2011 and 2016.

Following enactment of the New York State Budget for Fiscal Year 2020, the Enacted Budget Financial Plan for FY 2020 revealed a troubling action taken under the Medicaid program: the State deferred a payment, including $1.7 billion in State funds, that should have been made in March 2019.2 Instead of making the payment near the end of the month when it was due, the State delayed the payment by three days, shifting the disbursement from fiscal year 2019 into fiscal year 2020 in order to adhere to the program’s fiscal year 2019 budget and the State’s “Medicaid Global Cap.”3 This action was not a one-time event. The State deferred payments in previous years to remain within budgeted spending levels, but the magnitude of the latest occurrence is unprecedented and obscures the State’s fiscal standing and outlook.

As a result of the deferral, the State’s four-year financial plan for fiscal years 2020 to 2023 does not account for the full cost of the Medicaid program. Adjusting for the payment deferral and future unaccounted costs reveals the State’s financial plan understates the State’s Medicaid costs by a cumulative total of more than $9 billion. Recognizing these costs increases projected budget gaps to $3.5 billion in fiscal year 2020 and as much as $6.6 billion in fiscal year 2023.4

State leaders have two options to reconcile the disconnect between reality and the budget: (1) reduce Medicaid spending to be in line with budgeted amounts; or (2) achieve savings in other areas of the budget to offset growing Medicaid costs. The two options are not mutually exclusive. Absent corrective action, the State will exacerbate an already troubling situation by increasing the amount of deferred payments each year. Further deferrals would leave the underlying problem unaddressed and would be in effect an involuntary loan from providers and insurance plans caring for Medicaid patients. Instead, State leaders should rein in State spending and align the budget with true costs.

Troubling Trends in Medicaid Spending

Medicaid is a joint federal-state program administered in New York by the State Department of Health (DOH). The federal government pays at least half the cost of the program. States are responsible for the remaining share, and New York State has mandated that localities (New York City and the 57 other counties) pay a fixed portion that recently has averaged approximately 10 percent of the total program cost.5

In analyzing Medicaid spending trends it is instructive to distinguish between total spending and spending per enrollee. Total spending is strongly affected by changes in the number of enrollees, which are influenced by economic conditions (for example, a recession can increase enrollment) and by policy decisions to broaden eligibility. Generally, greater enrollment is viewed as a positive development enabling the program to reach more people in need. Spending per enrollee is often interpreted as an indicator of program efficiency. Growth in this indicator may reflect unnecessary service utilization or increasing provider payment rates that may be unsustainable; a drop in this indicator without decreasing the quality of care can be interpreted as improvement in program management.

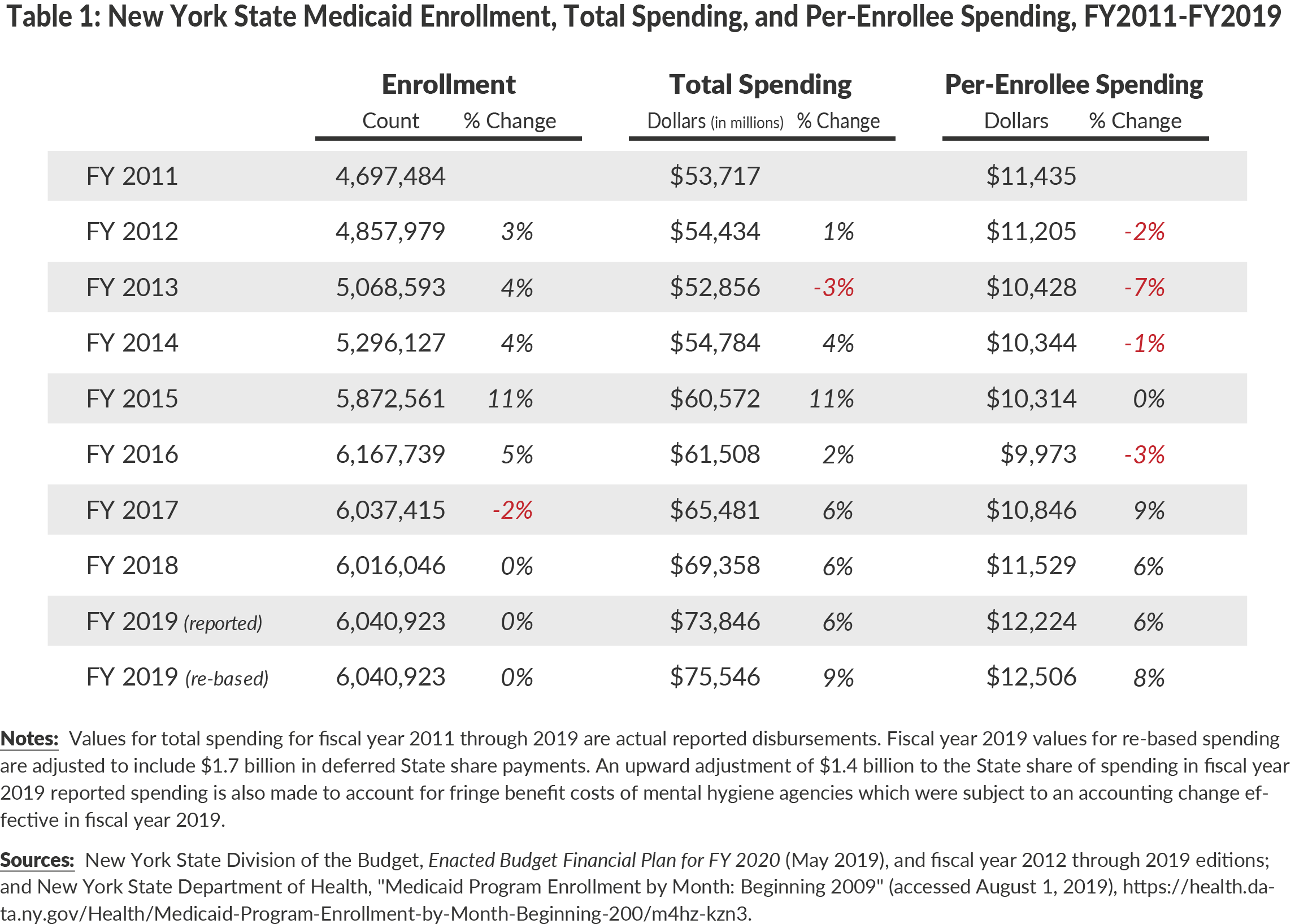

Since fiscal year 2011 Medicaid spending has evinced two distinct trends, with positive developments from fiscal years 2011 to 2016 and more troubling developments since. (See Table 1.) From fiscal years 2011 to 2016 the State leveraged provisions of the 2010 federal Affordable Care Act (ACA) to increase enrollment almost one-third from under 4.7 million to nearly 6.2 million. However, growth in total spending in this period was less than 15 percent because per-enrollee spending declined 13 percent from $11,435 to $9,973. Some of the drop in average per-enrollee spending was because many of the new enrollees were relatively healthy individuals that required low average spending, but much of it was related to program reforms designed and implemented by the MRT launched by Governor Andrew Cuomo in 2011. The MRT initiatives in this period included provider payment rate reductions and expansion of managed care enrollment and managed care covered services.

An important element of the MRT reforms is establishment in statute of a Medicaid Global Cap. While the “Global” adjective is a misnomer because the cap applies only to certain varying portions of State funded spending and the “Cap” can be adhered to by shifting timing of payments, it has proven useful by setting a limit on Medicaid spending growth based on the ten-year rolling average of the medical component of the consumer price index. If spending is likely to exceed this cap, DOH and the Division of the Budget (DOB) are empowered to take actions to reduce spending, including across the board rate cuts to enforce the cap.6

The troubling trend since fiscal year 2016 is per-enrollee cost has increased significantly. From fiscal years 2016 to 2018 cost per enrollee rose nearly 16 percent from $9,973 to $11,529. To calculate 2019 per-enrollee spending appropriately, the deferred $1.7 billion should be added back to its appropriate due date. In fiscal year 2019, when adjustment is made for the deferred payments, the cost increases another 8 percent to $12,506. The increased cost per enrollee has multiple causes including increases in the minimum wage for some service providers, growing use of long-term care services by an aging population, and increased supplemental payments to fiscally distressed hospitals. The rising cost per enrollee caused total spending to increase more than 25 percent from fiscal years 2016 to 2019 despite essentially flat program enrollment.7

Crediting State and Federal Medicaid Payments

Most Medicaid program costs are shared by the federal and state governments and state and federal funds are disbursed in tandem. (New York is unique in requiring a significant local contribution; however, the local portion is collected by the State and distributed to providers as part of the State share.) State officials informed CBC staff the federal portion of the total Medicaid payment that was delayed from March 2019 to April 2019 was credited back to March, while the State portion was credited to April. [8] Recording parts of the same payment to different fiscal years marks a significant departure from past practice and was not described in the State’s financial plan for fiscal year 2020. To calculate fiscal year 2019 Medicaid spending, this report adjusts the fiscal year 2019 State Medicaid costs but does not adjust the fiscal year 2019 federal Medicaid costs. Any reduction to State share funding that may occur in response to the State’s fiscal problem would result in an approximately equivalent adjustment in the federal share.

Realigning the Budget with Reality

The March 2019 decision to defer payments to fiscal year 2020 was explained in the Enacted Budget Financial Plan for FY2020 as a measure to adhere to the Medicaid Global Cap:

- “In FY 2019, DOH deferred, for three business days the final cycle payment to Medicaid Managed Care Organizations, as well as other payments. The deferral, which had a State-share value of $1.7 billion, was done to limit spending to the Global Cap indexed rate for FY 2019. Higher spending in FY 2019 appears to reflect growth in managed care enrollment and costs above projections, as well as certain savings actions and offsets that were not processed by year-end.”9

While the scale of this deferral is unprecedented, the State has deferred payments in recent years for similar reasons, stating that, “(T)he State has, at times, taken actions to manage the timing of Medicaid payments to ensure compliance with the Global Cap. Between FY 2015 and FY 2018, DOH managed the timing of payments across State fiscal years that ranged from $50 million to roughly $435 million."10

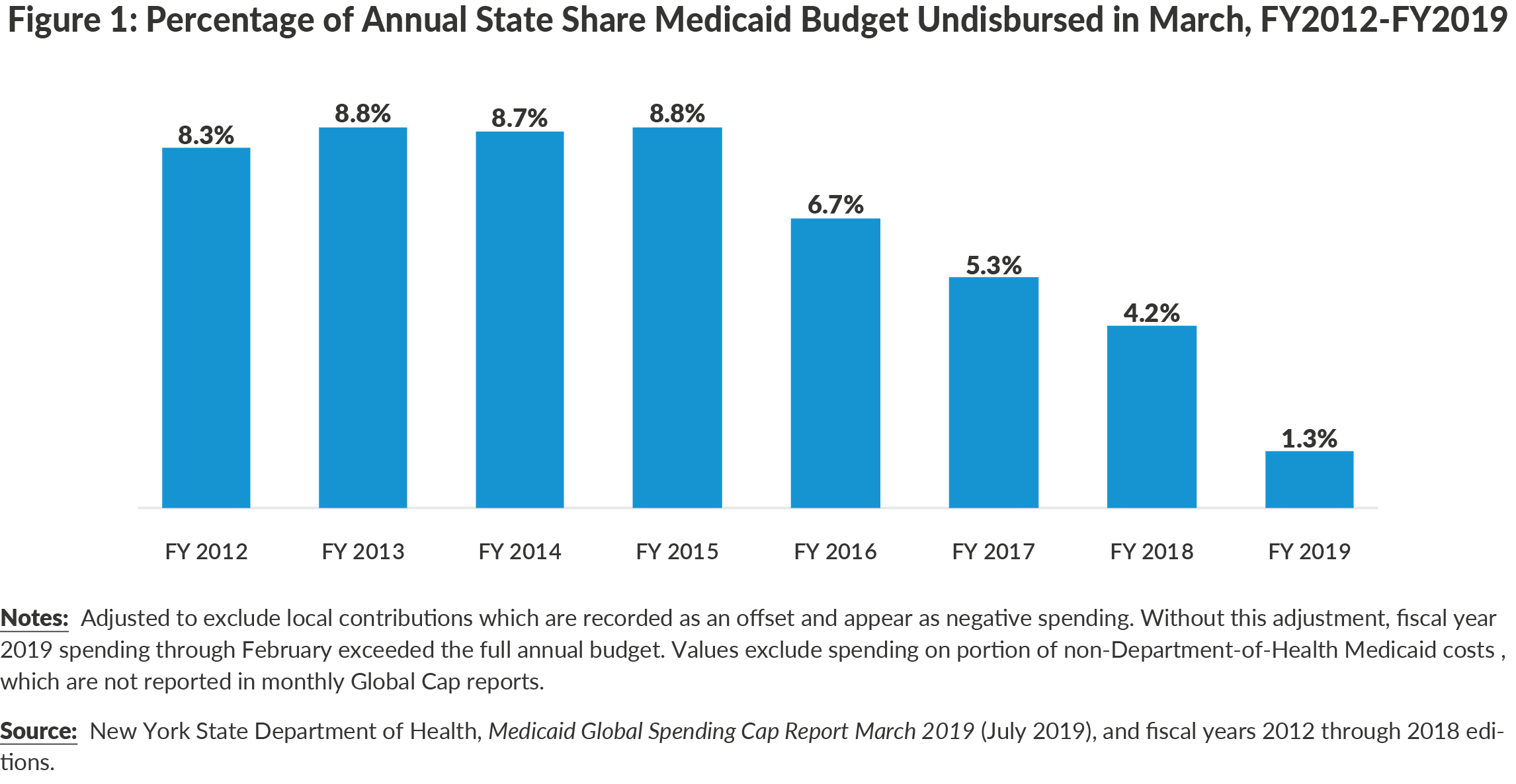

Figure 1 shows the share of the Medicaid budget not yet spent in the last month of each fiscal year from 2012 to 2019. In fiscal years 2012 to 2015 approximately one-twelfth of the annual budget remained available to pay the one-twelfth of costs that remained in March. In subsequent years the available funding for the final month of the year shrank, with just 1.3 percent of budgeted funds available in March 2019. As available funding declined some payments were deferred in order to adhere to the budget; however, the magnitude of previous deferrals apparently were not deemed sufficient to require postponing paying managed care premiums with a specific due date (as opposed to fee-for-service payments that can be less visibly postponed) or requiring disclosure in budget documents. Results of the first quarter of the current fiscal year show spending continues to exceed projections; State spending on Medicaid exceeded projections through June by $372 million or 5.1 percent.11

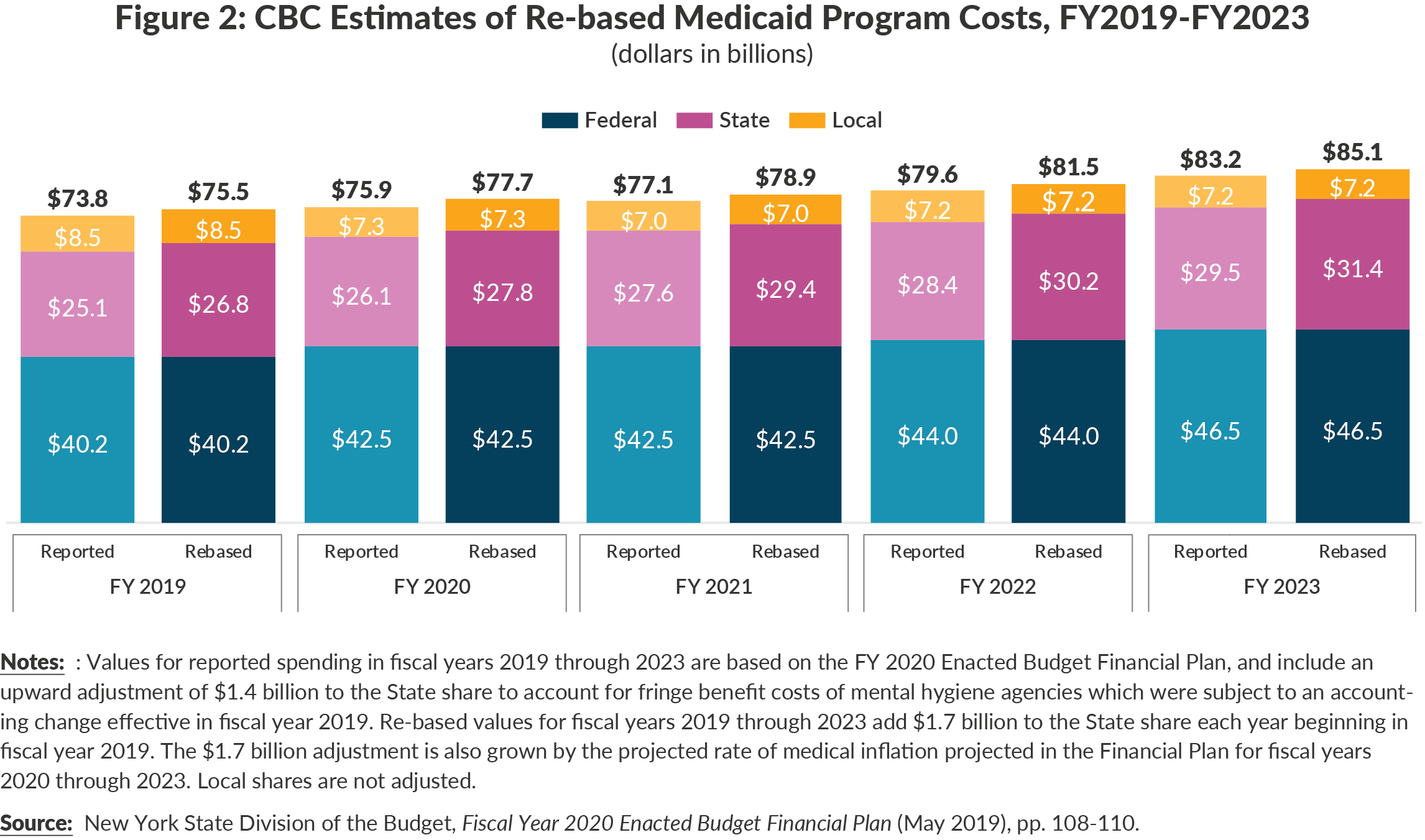

The significant deferral of spending at the end of fiscal year 2019 has unfortunate consequences for the State financial plan’s integrity in current and future fiscal years. The simple fact is the current financial plan does not account for the true costs of the Medicaid program. Figure 2 illustrates re-based projections for Medicaid in the affected fiscal years of 2019 to 2023. Re-basing requires adding $1.7 billion to the fiscal year 2019 State share to account for understated projections. The $1.7 billion adjustment is increased annually by the rate of medical inflation projected by DOB (approximately 3 percent annually). Re-basing is necessary because the current financial plan understates Medicaid costs by $1.8 billion in fiscal year 2020 and the variances increase to $1.9 billion by fiscal year 2023.12

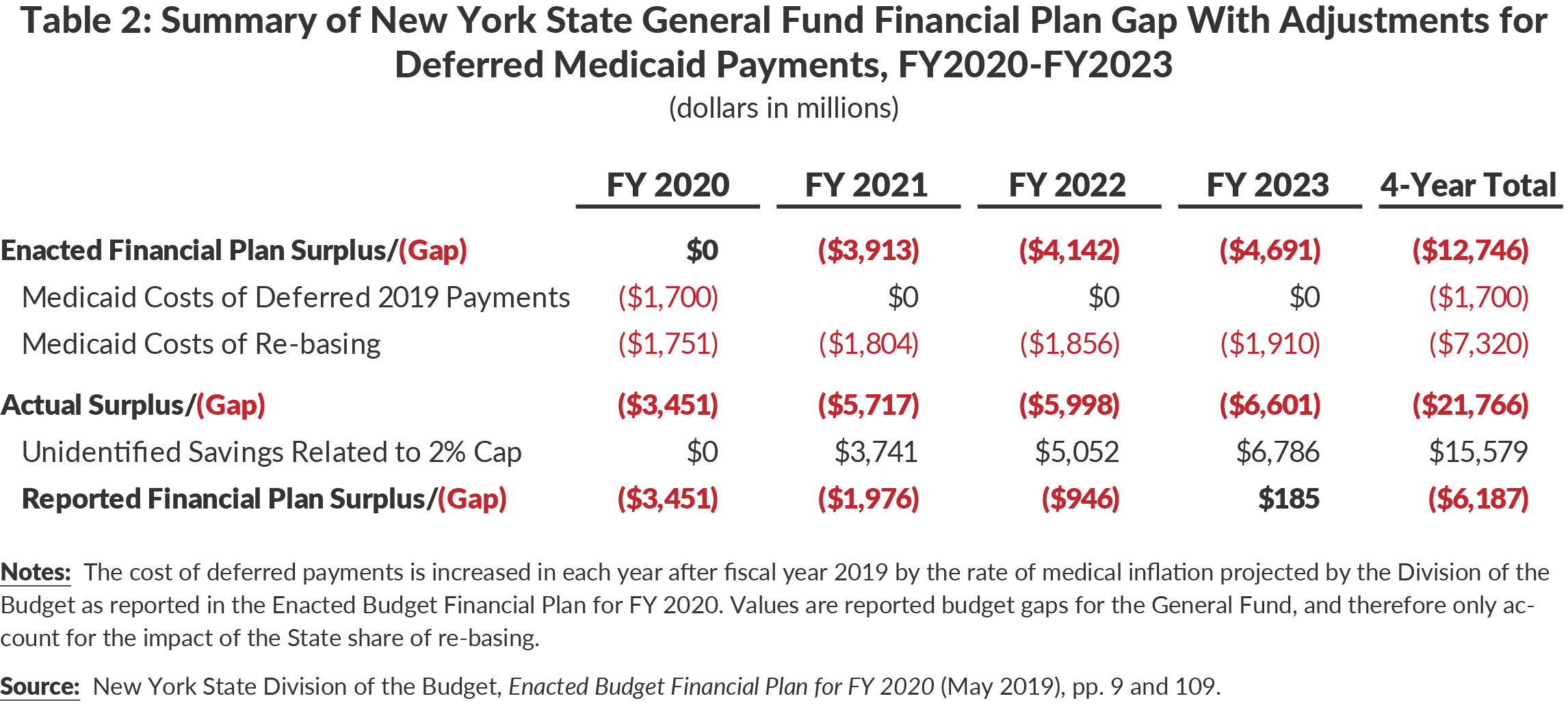

Accounting for true Medicaid program costs substantially increases the State’s budget gaps. Table 2 presents reported financial plan gaps, and adjusts them to account for the State making up the deferred March 2019 payment plus re-based Medicaid costs. The result is annual general fund spending gaps that grow from $3.5 billion in fiscal year 2020 to $6.6 billion in fiscal year 2023. The four-year financial plan’s cumulative shortfall grows $9 billion, from the originally reported $12.8 billion to $21.8 billion.13

Options for Returning to Fiscal Reality

The State has two—not mutually exclusive—options to address the understatement of Medicaid costs in the current financial plan:

- Reduce spending for Medicaid: The re-based spending projections presented exceed the State’s budgeted amounts for the State share of Medicaid by more than $3.4 billion in fiscal year 2020 and up to $9 billion annually in subsequent years for a four-year total of more than $9 billion. (See Table 2.) Cuts of this magnitude may not be achievable in this time period without negatively affecting patient care and undermining the financial viability of many providers and therefore the ability to deliver services. This option surely would face opposition by those directly affected. One-time resources from monetary settlements could be used to fund a transition period for Medicaid during which reductions are phased-in. Nonetheless, the daunting fiscal reality of rising Medicaid costs deserves a reinvigorated effort to achieve significant reductions in per-enrollee costs.

- Reduce planned spending for other services: Reductions in Medicaid spending sufficient to offset fully the unrecognized rising costs may be neither wise nor feasible, and the State should identify other spending reductions. Opportunities exist within economic development spending, particularly within unproven programs have been expanded.14 Furthermore, by insufficiently targeting education aid to high need districts, the State has repeatedly increased aid more than is necessary to fund a sound basic education (SBE) in every district. In fiscal year 2020 the State increased aid roughly $800 million more than was necessary to fund a SBE.15

The State has budgeted enough to pay for only approximately 11 months or 92 percent of certain Medicaid costs in the current and future fiscal years. In fiscal year 2020 it has already used some of its budget to pay for 2019 costs. Absent policy changes, the State would need to defer about $3.4 billion of State fund payments from fiscal year 2020 to fiscal year 2021 and significant sums in subsequent years. This is imprudent fiscal management because it imposes a burden on those serving Medicaid clients, obfuscates the State’s financial picture, increases the size of the problem by letting it grow unabated, and creates a large liability that eventually must be reduced by future taxpayers.

Conclusion

The State’s budget and financial plan understate the true costs of the Medicaid program by billions of dollars and past due bills have been accumulating. The State should not continue to obscure the true cost of Medicaid or financial plan spending obligations. It should align the budget with actual costs. This should be reflected in the Fiscal Year 2020 Mid-Year Update due at the end of this month. Alignment likely requires substantial reductions in spending—by reinvigorating the previously successful Medicaid Redesign Team, slowing the rapid growth in school aid by better targeting aid to needy districts, and cutting wasteful economic development spending—as well as other transitional arrangements. Sound fiscal management will require difficult decisions, but the current practice of large-scale deferrals is fiscally irresponsible and should not be repeated.

Download Report

Overdue Bills: Time to Face the Reality of Rising Medicaid CostsFootnotes

- Based on All Funds spending. Medicaid spending is 24 percent of State Operating Funds spending. Medicaid funding provided by local governments is not included in the State budget. See: New York State Division of the Budget, Enacted Budget Financial Plan for FY 2020 (May 2019, p. 110), www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy20/enac/fy20fp-en.pdf.

- By design and policy the federal government supports 50 percent of New York’s Medicaid program; thus, payments or savings of State funds are matched by the equivalent amount of federal funds. However, the federal portion of the fiscal year 2019 Medicaid payment that was disbursed in April 2019 was credited to March of 2019. See text box for further discussion.

- New York State Division of the Budget, Enacted Budget Financial Plan for FY 2020 (May 2019), p. 37, www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy20/enac/fy20fp-en.pdf.

- Budget gaps as reported before the State’s unidentified savings plan is implemented to adhere to the 2 percent spending cap. (See Table 3.)

- For more information, see: Patrick Orecki, Still a Poor Way to Pay for Medicaid (Citizens Budget Commission, October 2018), https://cbcny.org/research/still-poor-way-pay-medicaid.

- Chapter 59 of the Laws of 2011, Part H, Section 91.

- The State financial plan and other public documents reflect a deferral of $1.7 billion in State Medicaid spending from fiscal year 2019 to fiscal year 2020. However, the federal portion of that payment was credited to fiscal year 2019 in financial plan documents despite being paid in fiscal year 2020.

- Staff of New York State Division of the Budget, conference call with Citizens Budget Commission staff (October 9, 2019).

- New York State Division of the Budget, Enacted Budget Financial Plan for FY 2020 (May 2019), p. 37, www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy20/enac/fy20fp-en.pdf.

- Absent detail of these payment deferrals, CBC was not able to account for these in its calculation of per enrollee costs or increases. Source: New York State Department of Health, Medicaid Global Spending Cap Report: March 2019 (July 2019), www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/regulations/global_cap/monthly/sfy_2018-2019/docs/mar_2019_report.pdf.

- New York State Division of the Budget, Enacted Budget Financial Plan for FY 2020 (May 2019), p. t-77, www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy20/enac/fy20fp-en.pdf; and FY 2020 First Quarterly Update (August 2019), p. t-62, www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy20/enac/fy20fp-en-q1.pd; and Bill Hammond, Medicaid Overage: $665M and Rising (Empire Center for Public Policy, August 16, 2019), www.empirecenter.org/publications/medicaid-overage-is-at-665m-and-rising/.

- Actual and projected spending are impacted by many spending decisions directly and indirectly related to the Medicaid program. State policies affect federal, state, and local shares over time. Local share effects include the impact of the cap and takeover of local costs (which increases the State share) and patterns in lump sum supplemental payments that require local government financing. Federal share effects include lump sum supplemental payment patterns and conclusion of the Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) program after fiscal year 2020. The growth of the State share is also impacted by external cost drivers such as the minimum wage and local takeover, which together account for approximately one quarter of the growth of the State share on average from fiscal year 2019 through 2023.

- This would not be affected by delay of the federal portion of the delayed fiscal year 2019 payment .

- See: Riley Edwards, 10 Billion Reasons to Rethink Economic Development in New York (Citizens Budget Commission, February 2019), https://cbcny.org/research/10-billion-reasons-rethink-economic-development-new-york.

- See: David Friedfel, “Funding a Sound Basic Education in 2020” Citizens Budget Commission Blog (March 7, 2019), https://cbcny.org/research/funding-sound-basic-education-2020.