Making Hay While the Sun Shines

A Plan to Strengthen New York State’s Rainy Day Fund

Introduction

Following the Great Recession and prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, New York State experienced its longest economic expansion in modern history. During that time, the State added 1.4 million jobs, unemployment fell from 9.0 percent to 3.9 percent, tax receipts grew approximately 4 percent annually, and the State received nearly $13 billion from extraordinary monetary settlements. However, despite this unprecedented run of sustained growth in its economy and finances, the State added just $842 million to reserves, bringing the total to just $2.0 billion at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The State has been playing catchup with the threat of storm clouds looming on the horizon. While Governor Kathy Hochul and the Legislature made significant progress in recent years, bringing rainy day savings to $19.5 billion, additional improvements would ensure the State’s reserves are sufficiently robust over time to protect New Yorkers from a recession or severe emergency.

If like prior downturns, the pandemic-sparked recession had crushed revenues and federal aid had not been substantial, the inadequacy of the State’s reserves would have been devastating for New Yorkers during the pandemic and hampered the State’s recovery.

In early 2020, confronting the pandemic and associated economic shutdown fiscally unprepared—rainy day funds totaled just 2 percent of its State Operating Funds (SOF) budget—put the State’s finances and services at risk. With inadequate reserves and unknown federal aid, the State initially held back funds from school districts, local governments, businesses, and nonprofit organizations causing harmful uncertainty. Fortunately, the worst potential consequences were avoided, but not because the State had planned and saved appropriately; rather, the recession was brief, tax receipts exceeded expectations, and unprecedented federal COVID-19 aid was delivered.

To their credit, Governor Hochul (who led the effort) and the Legislature vastly increased the State’s reserves and improved the structure of the rainy day fund over the past two years. Still, more can and should be done. To protect existing reserves from misuse and ensure resources are appropriately saved going forward, the State should:

- Combine all principal reserves into the Rainy Day Reserve (RDR) lockbox immediately;

- Deposit up to an additional $2.4 billion to the RDR this year;

- Set a target for the RDR of 22 percent of SOF spending;

- Increase the maximum allowed RDR balance to 30 percent of SOF spending; and

- Mandate automatic RDR deposits when the economy is growing.

Rules Needed to Ensure Reserves Function as a Bulwark Against Economic Downturns and Catastrophes

A rainy day fund should provide the fiscal backstop necessary to mitigate the worst consequences of an economic downturn or severe emergency. Adequate and well-structured reserves enable states to continue critical public services when they are most needed, demonstrate a state’s strong fiscal position, and support improved credit ratings.1

A rainy day fund should have clear and appropriate rules about how it is structured and managed, including its target and allowable size, mandatory deposit policies, and withdrawal parameters.2

Target Size

A rainy day fund’s target size should be sufficient to weather a storm—to mitigate the most disruptive service cuts or counterproductive tax increases driven by recession or emergency. A target of 15 percent to 17 percent of annual spending is commonly cited, including by New York State.3 However, a specific state’s target should consider its revenue volatility, which may mean greater than typical revenue loss during a downturn. New York’s target should be higher than many because its revenues are particularly volatile, with 45 percent of its own source revenue coming from the economically sensitive personal income tax.

SOF is New York State’s most complete measure of operating spending; therefore, it should be used for setting the rainy day fund target. Currently, the State caps reserves relative to the General Fund, a subset of State spending that excludes roughly 25 percent of total operating spending.

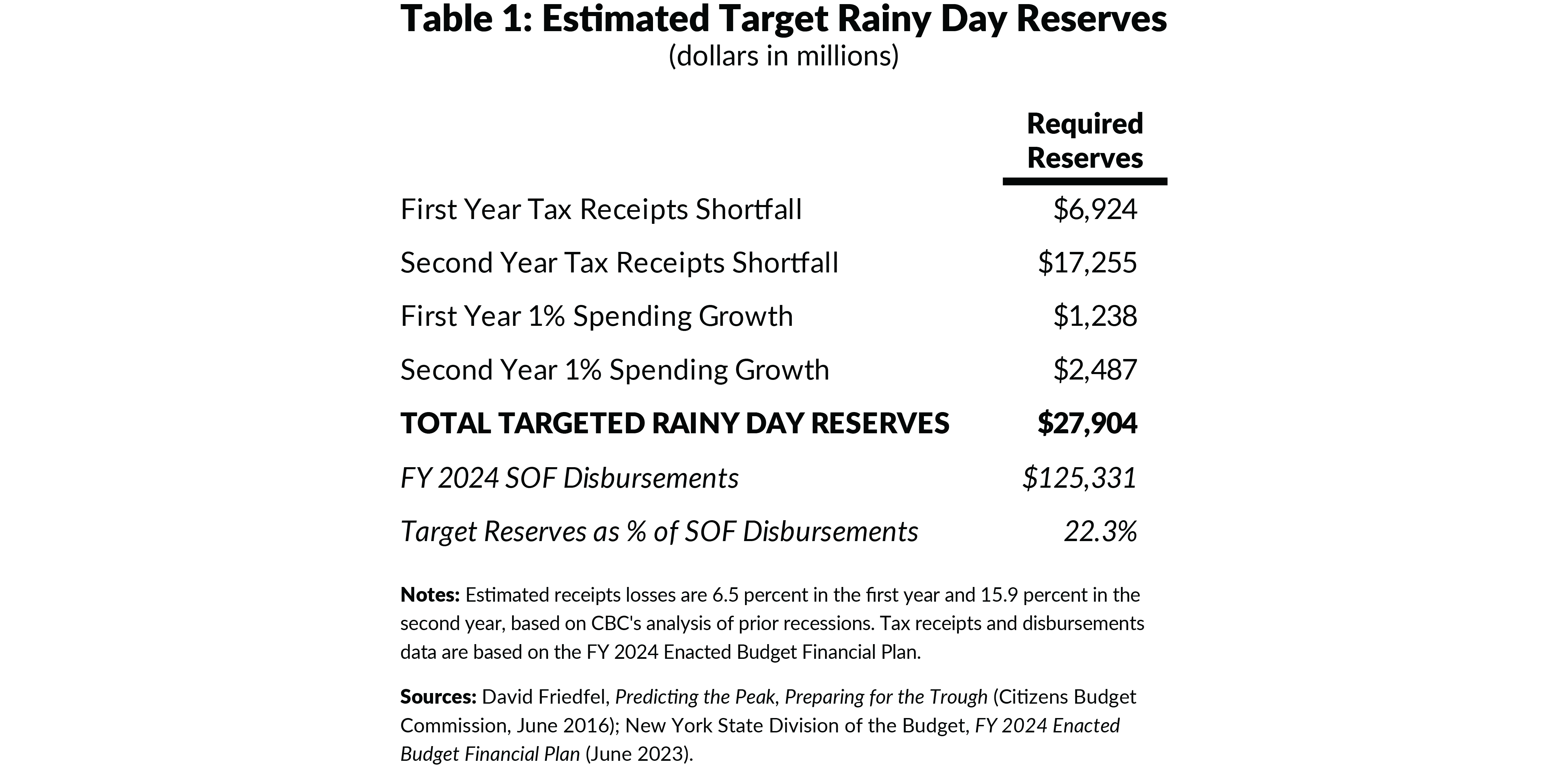

CBC recommends New York State’s rainy day savings should equal at least 22 percent of SOF, $27.9 billion for fiscal year 2024. This would provide reserves sufficient to cover two years of recessionary tax receipts losses and a 1 percent annual increase in SOF spending. During the last three pre-pandemic recessions, tax receipts on average were 6.5 percent lower than projections in the first year and 15.9 percent lower in the second year.4 Applied to current projections this would result in a two-year shortfall of $24.2 billion. (See Table 1.) Spending growth of 1 percent annually would total $1.2 billion in the first year and $2.5 billion in the second.

Mandatory Deposits

New York’s history clearly demonstrates the need to mandate annual deposits to help ensure adequate rainy day savings are accumulated during economic expansions.5 The State would not have missed the opportunity to save during the 2010 through 2019 expansion if it were required to make deposits. The requirement should tie deposits to tax receipt growth, so that funds would be added to the rainy day fund in particularly strong economic periods.

The State should deposit two-thirds of tax receipts growth in excess of 2 percent annually into the rainy day fund.6 This would meaningfully grow the Fund and still allow spending to increase with tax receipts.

Furthermore, some portion of one-time extraordinary receipts, such as those from legal settlements, should also be deposited into rainy day savings. These receipts are non-recurring and should not fund recurring operations; instead they should be used for rainy day savings, capital expenditures, or other one-time uses.

If the State had made these automatic annual deposits from fiscal year 2011 to fiscal year 2020, plus added three-quarters of its one-time extraordinary receipts, the balance in its Rainy Day Fund would have exceeded $23 billion in 2020.7

Maximum Size

Revenue shortfalls are likely to extend past two years and reserves in excess of 22 percent of SOF can be very beneficial. Still, capping the fund at 30 percent is reasonable, as it would permit robust savings and ensure that mandatory deposits to the fund would not inordinately constrain operating resources that can be used to benefit New Yorkers. Once this cap is reached, deposits can instead be directed to the Retiree Health Benefits Trust.

Withdrawal Limitations

There also should be clearly defined criteria for withdrawing funds, lest they are used when there is not a recession or severe emergency with significant revenue losses or expenditures increases.

Replenishment Requirements

If the use of funds is appropriately restricted and annual deposits are mandated based on a formula that accounts for economic growth, replenishment rules may not be warranted. In fact, replenishment timelines can discourage use of the reserves at appropriate times and may also require faster and larger deposits coming out of a recession than what an economically based, formula-driven deposit rule recommends.

New York’s Rainy Day Reserve Still Falls Short in Size and Structure

NYS currently has $19.5 billion in “Principal Reserves,” the moniker the State has used for its rainy day fund and related savings. Another $23.9 billion is held in other funds, primarily to manage debt service payments, level tax receipts from the pass-through entity tax, plan for new labor contracts, and other purposes. (See Figure 1.)

While the State refers to the $19.5 billion in the Principal Reserves as its savings for a rainy day, the funds possess two fundamental deficiencies. First, they are $8.4 billion short of the CBC’s recommended level. Second, just $6.3 billion (in the Rainy Day Reserve and Tax Stabilization Reserve) has guardrails to help ensure the funds are only used during a recession or defined emergency. Roughly two-thirds of total rainy day savings can be tapped by the State at any time for any use, putting them at risk of use in fiscally imprudent circumstances.

The Principal Reserves are made up of three funds:

- Rainy Day Reserve (RDR): The RDR is the State’s main lockbox for savings. Established in 2007, its balance was initially capped at just 3 percent of General Fund spending. Over time, the balance cap has been raised; the Fiscal Year 2024 Enacted Budget increased the allowable balance to 25 percent of General Fund disbursements. Deposits are currently discretionary, but are capped; over time the annual deposit cap has been increased to 15 percent of General Fund disbursements. The balance can only be used in periods of economic downturn or catastrophes, clearly defined in State law. If withdrawals are made, the balance must be replenished within three years.8

- Tax Stabilization Reserve (TSR): The TSR is limited to a balance of 2 percent of General Fund disbursements and annual deposits are capped at 0.2 percent of General Fund disbursements. These deposits are required in years of General Fund surplus. The balance is used to cover short-term decreases in tax receipts.9 While this limitation helps ensure the funds are not used at whim for episodic policy or political priorities, it is not the appropriate way to limit withdrawals for a defined emergency or recession.

- Economic Uncertainties Fund (EUF): The EUF is not set up in statute and has no rules for deposits, balances, target size, or use. If the RDR is a lockbox, the EUF is a shoebox. Its contents can be withdrawn without limitation or required replenishment.

Recommendations to Further Improve Rainy Day Savings

New York State’s leaders—especially Governor Hochul—deserve praise for repeatedly increasing the allowable and actual size of reserves. However, additional improvements would strengthen the State’s savings, better allowing it to protect New Yorkers from recessions or emergencies.

The State should:

- Combine all principal reserves into the Rainy Day Reserve (RDR) lockbox immediately. With higher caps on the RDR, the State can immediately move the full balance of the EUF to the RDR, ensuring the appropriate protection for the entirety of the State’s reserves. (See Figure 2.) CBC further recommends statutory changes to allow the TSR balance to be transferred to the RDR, and for all reserves balance to be held in the RDR going forward.

- Deposit up to an additional $2.4 billion this year to the RDR this year. Up to $2.4 billion may be transferred to the RDR under current law after the EUF is transferred. This should be a priority for any excess mid-year receipts or underspending.

- Set a target for the RDR of 22 percent SOF spending. The State’s RDR balance should be at least 22 percent of SOF disbursements, $27.9 billion for fiscal year 2024. This level of savings would be enough to mitigate two years of recession tax receipts shortfalls while allowing two years of 1 percent SOF disbursements growth.

- Increase the maximum RDR balance to 30 percent of SOF spending. Having a maximum size greater than the target provides capacity for the third year of a recession, without over limiting the State’s ability to provide services as receipts are realized. Still, it is wise to use funds that would be deposited into the fund were it not for the balance cap for other one-time purposes such as capital expenditures or paying down debt, rather than for recurring programs.

- Mandate RDR deposits when the economy is growing. Requiring deposits during economic expansion builds needed reserves. Deposits should equal to two-thirds of common rate and base tax receipts growth in excess of 2 percent annually should be required. Once deposits are automatic and formula-driven, existing replenishment rules should be reconsidered. Furthermore, the State should consider whether to mandate the deposit of a portion of one-time extraordinary revenues, such as legal settlements.

Conclusion

Increasing the deposits into and size of the State’s reserves is arguably New York’s most significant fiscal achievement in recent years. Today, the State’s reserves are 10 times larger than they were just 5 years ago. More can and should be done. A well-funded and structured RDR would help New York State weather future recessions without harmful service cuts or counterproductive tax increases. CBC’s additional improvements should be first implemented as policy, but should be legally mandated and ultimately imbedded in the constitution. They would go a long way toward building a rainy day fund to weather a storm, and help protect New York’s future.

Footnotes

- Office of the Comptroller of New York State, The Case for Building New York State’s Rainy Day Reserve (December 2019), www.osc.state.ny.us/files/reports/budget/pdf/rainy-day-reserves-2019.pdf; and The Pew Charitable Trusts, Rainy Day Funds and State Credit Rating (May 2017), www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2017/05/statesfiscalhealth_creditratingsreport.pdf.

- See Charles Brecher, Thad Calabrese, and Ana Champeny, To Weather a Storm (Citizens Budget Commission, April 18, 2019), https://cbcny.org/research/weather-storm.

- New York State Division of the Budget, FY 2022 Mid-Year Update (October 2021), p, 9, https://openbudget.ny.gov/historicalFP/fy22/en/fy22en-fp-myu.pdf.

- See David Friedfel, Predicting the Peak, Preparing for the Trough (Citizens Budget Commission, June 20, 2016), https://cbcny.org/research/predicting-peak-preparing-trough.

- For a discussion of the role of mandatory deposits in building up balances, see: Mariana Alexander and Timothy Sullivan, California Dreaming: New York Should Build Reserves to Prepare for a Rainy Day (Citizens Budget Commission, March 12, 2018), https://cbcny.org/research/california-dreaming.

- This should be calculated on a common rate and base to ensure that changes in tax policy do not hamper the State’s ability to save.

- Patrick Orecki, Accounting (and More) for a Better Budget (Citizens Budget Commission, December 20, 2022), https://cbcny.org/research/accounting-and-more-better-budget.

- Section 92-cc of State Finance Law.

- Section 92 of State Finance Law.